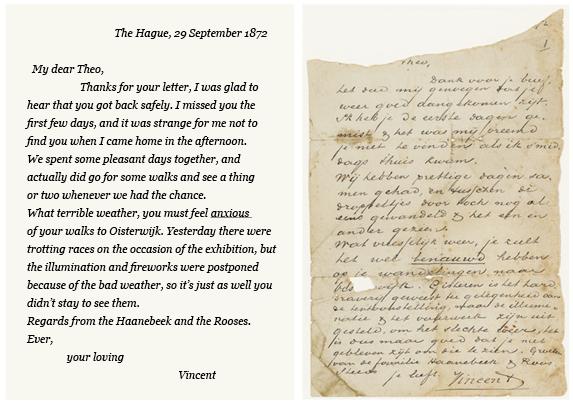

‘My dear Theo, I was glad to hear that you were back safely. I missed you the first two days and it was strange for me not to find you when I came home in the afternoon’. This is the earliest exemplary from the complete correspondence of Van Gogh that survives today. Although Vincent is just nineteen years old when he pens it, he has already been working at the Goupil & Co art gallery in The Hague for some three years. Theo is fifteen at the time, and is returning home to his parents in Helvoirt, in North Brabant after a few days with his brother in the capital. He attends school in Oisterwijk, and travels there by foot – a six kilometer walk each way in the abundant wind and rain of that stormy Autumn. Vincent’s handwritten letter is torn at the top, but the date has been estimated thanks to the mention of the trotting races, which were held on Saturday, September 28th, 1872. Vincent has his younger brother at heart, ‘you must feel anxious’… he is a protective and affectionate older sibling, and will become even more so when Theo begins working at the Brussells branch of Goupil at the start of the new year. Read this, read that, visit these museums, take lots of walks ... ‘Your loving Vincent’.

Letter of Vincent to Theo, The Hague, 29 September 1872, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

‘Your Loving Vincent’: Van Gogh’s Greatest Letters is the title of a new exhibition currently running at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (from 9 October to 10 January 2021). Curated by Nienke Bakker, in collaboration with Ann Blokland, the exhibits are grouped into five sections –Fraternal love, A new destiny, Real life, Big dreams, In search of stability. These five themes sketch a portrait of Van Gogh through his letters, an image made of words that gradually restore to Vincent some of what has been taken from him. Few other artists have had their words so freely copied and pasted ad hoc to demonstrate this or that. The same can be said of Vincent’s self-portraits, so often splashed across the covers of books or magazines, cropped to zoom in on a disturbed expression, tirelessly reiterating the myth of the damned soul, the impulsive artist, penniless, alone, ignored by the critics. We have 820 of the letters he wrote, and 83 of those he received. These introduce us to a completely different individual, in stark contrast to the stereotype cemented over the twentieth century and reinforced on the big screen (even in recent productions). On the one hand there is a miserable person, who stones are thrown at, who paints on impulse – and on the other hand there is a very subtle mind, a man who visits museums, a patient and attentive reader who reflects on the works of Shakespeare and Rembrandt. There is a mountain of contradictions, Giovanni Testori was right back in 1990 when he admonished the critics for their ‘definitive cowardice’.

A selection of around 40 letters are displayed alongside some 20 paintings and drawings which offer a window into Vincent’s inner world. Thus we garner a closer glimpse of the artist, the authentic being, and his complex and multifaceted character. The letters are extremely delicate, light-sensitive sheets of paper that are rarely exhibited. They span 18 years, from the earliest surviving letter in 1872 to the final one from 23 July, 1890, just four days before he shot himself in the chest.

The material on show is further enriched by a selection of modern-day letters: last year the Van Gogh Museum invited people from all around the world to submit their most cherished letters, offering them the opportunity to have these letters exhibited next to Van Gogh’s. Sent from countries including Kosovo, the USA and Israel, the finest of these are on display. These modern-day letters speak of lost love, reclaimed friendship and much more. They show how the profound value of ‘old-fashioned’ writing, receiving and keeping still applies today. The exhibition is accompanied by Vincent van Gogh. A Life in Letters, edited by Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten, a new anthology of Van Gogh’s letters, with authors’ commentary and illustrations of the original manuscripts and sketches.

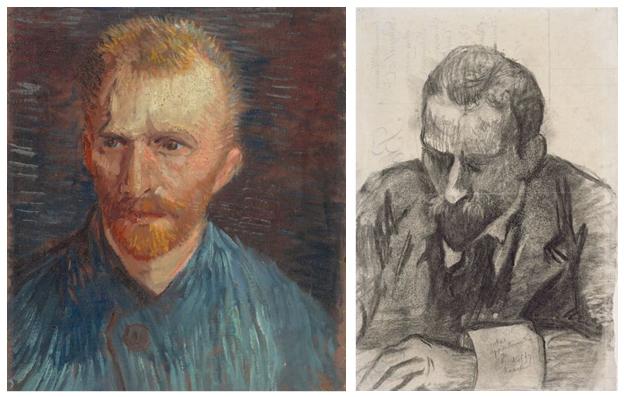

From the left: Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, oil on canvas, 1887; Meijer de Haan, Portrait of Theo van Gogh, pencil and chalk on paper, 1889, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

Vincent & Theo

The brothers had a startling resemblance to each other. To cite two recent examples of this: for the last 60 years it was thought that there was a photograph of Vincent aged 13, in addition to the much more famous one that he himself commissioned at age 19. Instead, thanks to a research conducted in 2018 by Teio Meedendorp and Yves Vasseur, it has emerged that the curly-haired boy published and identified in so many books as the young Vincent could not be him. In fact, the researchers discovered that the photographer Balduin Schwartz had opened his studio in Brussells in 1870, when Vincent was already 17 years old. The photograph is therefore of Theo, who was 15 at the time.

The second example is a small oil portrait that Vincent painted in 1887, a man in a straw hat. For many years researchers have had conflicting opinions on this work: who is the subject – Vincent or Theo? Last year this diatribe ended with a compromise – a double title was given to the painting: Self-Portrait or Portrait of Theo. Ultimately, the identity of the model remains a mystery.

The portraits of the two brothers selected for this exhibition further confirm the resemblance between them. There is a beautiful self-portrait by Vincent, painted in his Parisian period (1887). It is part of a number of “reused” canvases, where the artist painted on the reverse of older works (in this case it was an early ‘Study for The Potato Eaters’). The gaze, pointed and vigilant, is especially interesting: the artist challenges the spectator, he doesn’t address the audience directly, looking elsewhere.

Then we see Theo, (probably) intent on writing, in a drawing by the Dutch artist Meijer de Haan. Seen this way, side by side, the subject of these two portraits could undoubtedly be the same person. Nevertheless, the personalities of the two brothers were profoundly different, one accommodating, the other radical, as revealed in a “double” letter, an exchange that took place between 5 and 9 January 1882.

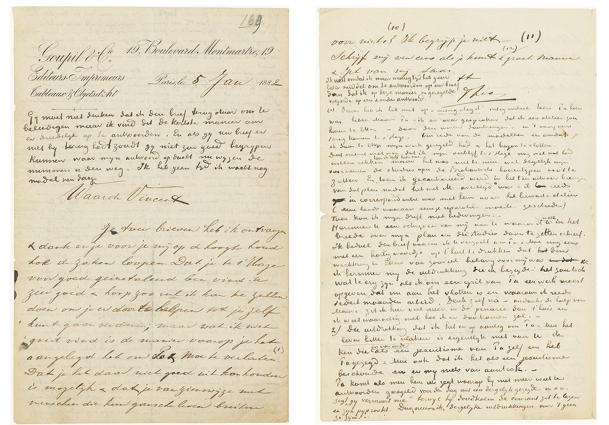

From the left: letter from Theo to Vincent, Paris, 5 January 1882 (first page); and letter from Vincent to Theo (first page, from below Theo’s signature), The Hague, 8-9 January 1882, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

This document is one of a kind, a “double” letter because it was written by both brothers, or to clarify: Christmas 1881 - after a furious row with his father (Reverend Theodorus), Vincent flees his parents’ home and moves to The Hague. In early January, Theo writes to him from Paris, trying to repair the damage. Vincent does not agree with Theo’s advice at all, and so, between the lines of his wise brother’s letter, he inserts numbers in round brackets – from 1-12 across the various pages – and returns the letter to the sender with addition of replies clearly listed out, point by concise point. And so Theo receives his own original letter back with annotations, added by Vincent in the empty space on the last page (never waste space), and followed by six further, crowded pages.

Where there was still a little room on the first sheet under the letterhead of Goupil & Cie, Boulevard Montmartre, Vincent carved out the space for this message: ‘You mustn’t think that I’m sending the letter back to insult you, but I find this the quickest way to answer it clearly. And if you didn’t have your letter back, you wouldn’t be able to understand what my answer refers to, whereas now the numbers guide you. I have no time, I’m waiting for a model today’. Vincent did not have an easy character, he was uncompromising, no half measures. The break with his father seems irreparable, Vincent will not be moved. Theo is the only one who understands him, who supports him throughout his artistic career, even when he does not agree with his choices, or when soon after he would decide to live with Sien, the pregnant prostitute he desired to marry and thus save from the streets. Hospitalised for syphilis that same Summer of 1882 in the Hague, Theo visited him. Shortly afterwards his father too went to his bedside, he was concerned for his eldest son and spoke to his physician. Vincent is reassured, Theo has succeeded in mediating.

From that Summer of 1882 onwards, Theo took on all responsibility for his brother, he would support him morally and materially for the rest of his life. Theo believed in his talent, and Vincent, well aware of the investment his brother was making, considered ‘all’ of his work to be Theo’s property, as ‘an advance’ for the money received. From Holland, he would always send very orderly crates, series of paintings and dozens of drawings, the fruit of his attentive and methodical advancement.

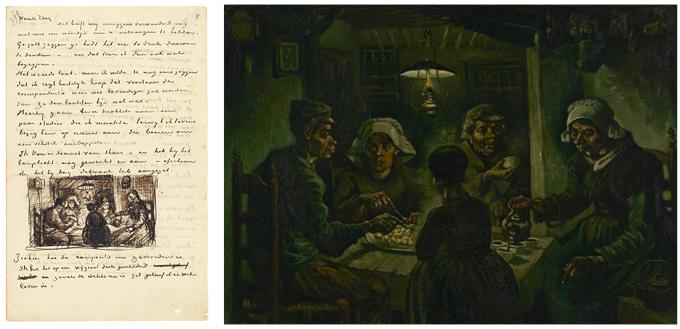

The Potato Eaters is his first great masterpiece. The crate with ‘the peasant painting’ which Van Gogh sent to Theo in Paris is initialed V1 – the outcome of a Winter spent painting heads of peasants, ‘if 50 aren’t enough, I’ll draw 100 of them’, he wrote. It is also a point of arrival conceptually, for Van Gogh it is the kind of art that will get city people thinking: ‘they get something useful out of paintings like that’, he wrote underlining the text.

From the left: letter from Vincent to Theo, with sketch of The Potato Eaters, Nuenen, 9 April 1885; Vincent van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, oil on canvas, 1885, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

The sketch we see in the letter of 9 April 1885 shows how easy it was for Vincent to give the idea of the greatness of his original artwork in a miniature of just 5 centimetres by 8.5. In the sketch, like in the painting, the composition rotates around a precise centre: the head of the figure we see from behind. Theorised in 1980 by the art critic Michael Fried as a figure of ‘absorption’ – as opposed to ‘theatricality’ – the figure whose shoulders are turned to us (on the scene but totally ‘absorbed’ in what she is doing) is the element which drags us into the painting, seating us before the steaming potatoes. But this sketch of The Potato Eaters was not the first and would not be the last. Vincent kept his brother updated on his progress and, from canvas to canvas (the ‘final’ work was preceded by two studies in oil), from sketch to sketch, his reflections deepen. Minimal movements, tiny changes of angle, the chairs, the hands, the eyelines … this is how he went on, how he focused his ideas, from big to small, from small to big: starting point – arrival – new starting point, an invaluable research process.

Van Gogh often drew in between words, and today we have over 240 letters with sketches, precious elements under many aspects, especially for dating his artworks. Sometimes he bordered the images and added explanatory notes. Other times the sketches were so small, like postage stamps, that they became an integral part of the text. In yet other cases, he devoted a whole page or even pages to drawings that expressed what he currently had on his easel. He generally used the same pen and ink, sometimes added touches of watercolour, especially in his Dutch period. Or he made a sketch that was an independent sheet of paper that he added in his letters to show Theo or his painter friends what he had in mind.

The empty nest, a sheet enclosed with a letter to his brother on 4 October 1885 is perhaps one of the most poetic sketches of Vincent’s. Under the image he wrote: ‘In the winter, when I have more time for it, I’ll make several drawings of this sort of thing. I feel for the brood and the nests – particularly those human nests, those cottages on the heath and their inhabitants’.

Letter from Vincent to Theo, with sketch of Bird’s Nest, Nuenen, c. 4 October 1885, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

As French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote (in The Poetics of Space, 1957) ‘A nest, like any other image of rest and quiet, is immediately associated with the image of a simple house. When we pass from the image of a nest to the image of a house, and vice versa, it can only be in an atmosphere of simplicity’. And Vincent, who collected bird nests of various kinds to paint, also depicted many houses with thatched rooves, human nests in the dusk. ‘For the painter [Van Gogh], it is probably twice as interesting if, while painting a nest, he dreams of a cottage and, while painting a cottage, he dreams of a nest’. Vincent loved nature, solitude, and was very attentive to birdsong (an interest he shared with his father since childhood). The family was familiar with Jules Michelet’s famous book, L’oiseau (The Bird, 1856), in which the author dedicates a passionate chapter to Le nid. Architecture des oiseaux (The Nest: Architecture of Birds) which may have been a source of inspiration. ‘The birds – like the wren or golden oriole – can also truly be counted among the artists’, Vincent wrote to his friend Anthon van Rappard in August 1885, sending him some nests from his large collection. Soon afterwards, in late November of the same year, he would leave Holland never to return.

During the two years Vincent spent in Paris (1886-88), there were some difficult moments between the brothers. At a certain point Theo seems exasperated, and in March 1887 he confides in their sister Willemien, living together has become ‘almost intolerable’: Vincent has a difficult character. But he is a man of his times, a genius with an uncommon literary and artistic patrimony, which amazes Gauguin and Andries Bonger, Jo’s brother. He absorbs and dispenses with the lessons of the Impressionists at warp speed, he reads and paints piles of books, he collects hundreds of Japanese prints. Theo knows the Parisian avant-garde well, however when Vincent leaves for Provence, he feels a great emptiness. He writes Wil: ‘It was through him that I came into contact with many painters who regarded him very highly. He’s one of the champions of new ideas…’. Two very different characters: they don’t always agree, but the brotherly bond is strong enough to overcome many obstacles.

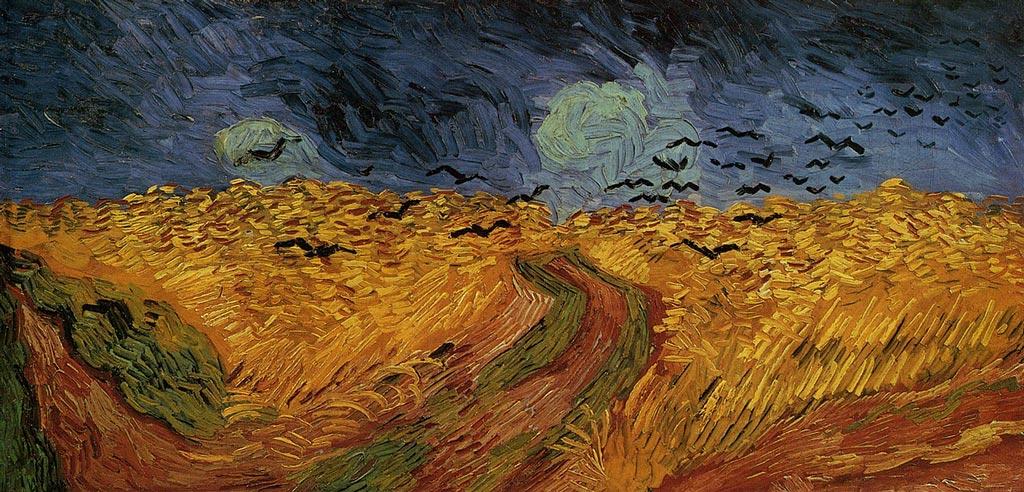

From the South of France their lively correspondence takes up again, the close-knit brothers adjusting to the new distance between them. In Provence, Vincent lives the most luminous season of his life – followed, as is well known, by a year in the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Rémy, when his lines are imbibed with the lucidity of one who is determined to resist. Art is ‘the best lightning conductor for the illness’ he writes to his brother. Returning back North to Auvers-sur-Oise in May 1890, he steps up his production more than ever, but the lines he writes are tainted with melancholy. He does not have much time left, seventy days in total. There are two versions of his last letter to his brother, probably both written on 23 July 1890: there is the letter he actually sent (with four beautiful sketches), and an earlier, unfinished (similar) version that was found on his person when he wounded himself on 27 July – as we can see from a note Theo wrote on the manuscript (on show).

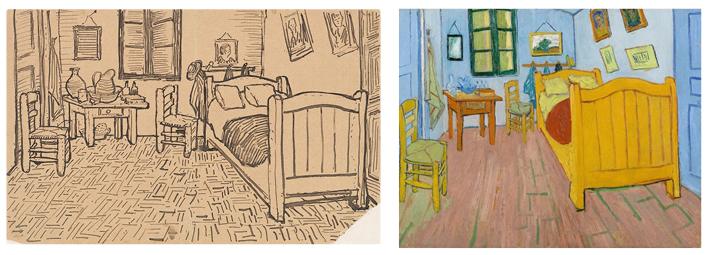

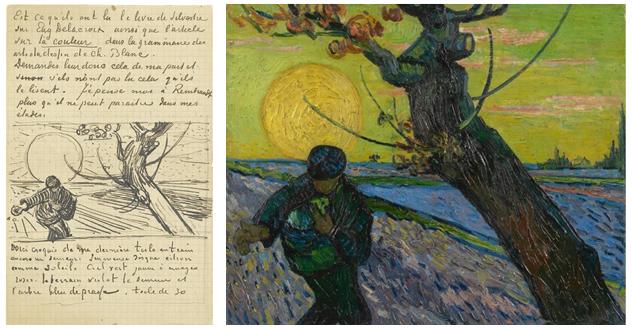

There are many reflections that emerge in this exhibition from the comparisons between the paintings and the sketches on the letters, particularly of famous works like The Orchards in Blossom, The Sower with an ‘immense yellow lemon disc for the sun’, or the much loved Bedroom. The ‘croquis’, the sketch included in the letter of 16 October 1888, roughly traced out from Theo with his ‘eyes still tired’ but as an example of ‘a new idea in mind’, shows us many differences with respect to the painting, starting with some simple objects. The most interesting aspect, however, is that on the canvas Vincent distorts the perspective, and manages to make the objects float, as if in a dream. He describes his canvas in detail, wanting to communicate a simple image ‘suggestive here of rest or of sleep in general. In short, looking at the painting should rest the mind, or rather, the imagination’. A nest that would last just some brief months.

From the left: sketch of The Bedroom, enclosed in a letter from Vincent to Theo, Arles, 16 October 1888; Vincent van Gogh, The Bedroom, 1888, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

The Letters, Vincent & the others

Thoughts on life, art and literature, a treatise on painting, a debate on art, for Vincent letter-writing was all this and more. Today considered a literary work in their own right, his letters are the fruit of a constant need, the most simple, basic human need – to communicate. To dialogue with others on themes such as life and death, religion, art and poetry… The need to talk about his big dreams, as well as his ambitious goals. It’s difficult to delineate the confines, especially during his months of illness, when the lines he wrote were so intense and moving, an existential dialogue with himself and with Theo, but also touching us as we read.

Vincent had a talent as a writer. Even in some of the letters he wrote in his youth, from London, we discover how natural it was for him, when he was struck by a landscape, to compare it to a description he had read in a book (for example, in that period, George Eliot). Naturally this aspect, the continual linking of the visual with the verbal, was ever more alive in Vincent during his years as an artist. Part of his style, his way of giving the idea of something so vivaciously and with such immediacy, whether it was a sky, a character or a face – faces he chose from novels, or from paintings. Sometimes his comparisons surprise us: for example, his doctor, who treated him for syphilis in the hospital of the Hague, ‘resembles some heads by Rembrandt, a fine forehead and a very sympathetic expression’. Thinking about it, he must have been right, because Rembrandt painted the common man. In Provence, the homeland of Tartarin, the local people gave him this impression: ‘it’s all something out of Daumier come to life’. In the hospital of Saint-Rémy, rereading Shakespeare, he found it so ‘alive’ that the characters seemed like modern day people to him …

It would be inappropriate to compare his letters to a diary, as is sometimes suggested. Van Gogh tells us very little about his practical habits. We know almost nothing of his daily routine, where he ate, where he purchased his books or art materials, or where he met his friends. During his life he changed address over thirty times, living in four different countries around Europe, but how he organised his moves remains a mystery. ‘In an era when many people rarely left the area of their birth or perhaps just moved from the countryside to the city, Van Gogh’s lifestyle was all the more remarkable, with constantly changing nations and cultures’, Martin Bailey noted in his book Living with Vincent van Gogh. The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (2019). Since 2015, the places where Vincent lived and worked have been the focus of great attention, to promote and preserve his legacy (‘Van Gogh Europe’, created for the 125th anniversary of the artist’s death). In these difficult times, it is also nice to ‘visit’ these places again as they were thirty years ago, and to follow Van Gogh’s footsteps in Sulle tracce di Van Gogh. Un viaggio sui luoghi dell’arte, by Gloria Fossi (2020). We are accompanied by the beautiful images of the time by the Italian photographers Mario Dondero and Danilo De Marco, and the fascinating insights by Fossi. The images presented interact with the works, and, of course, with Van Gogh’s letters.

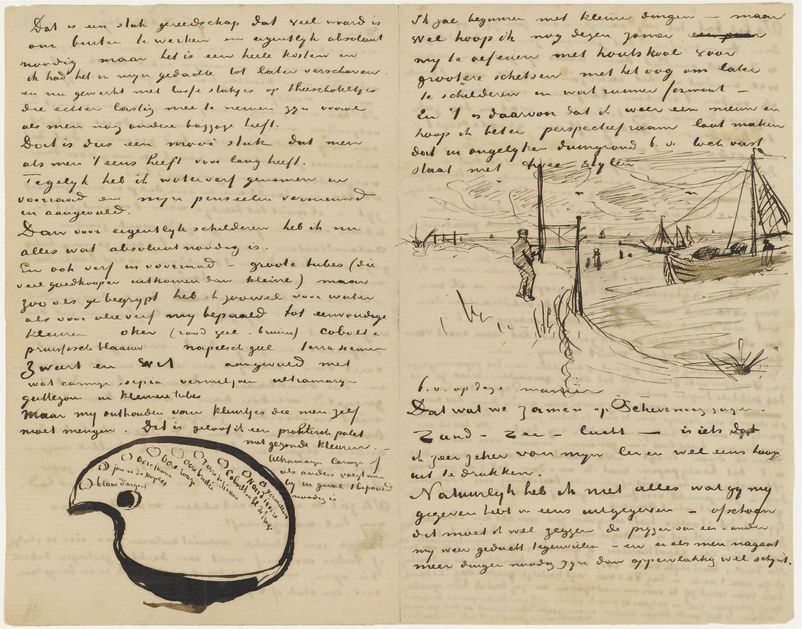

Letter from Vincent to Theo, with two sketches: Van Gogh’s palette and Beach at Scheveningen with perspective frame, The Hague, 5 August 1882, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

An avid reader and nature-lover who admired the simple folk as much as the greatest writers – there are numerous letters that tell us about the books Vincent read, day after day. ‘Ouvrier’ – labourer to art – as he sometimes defined himself, he was proud to describe his continuous advancement in his artistic work, on which he wrote in minute detail. We often come across little sketches of art materials, like his palette, or of the perspective frame he had had mad e for himself specially for use on the dunes, to ‘stand firmly on two legs’. We see a nice example of this on the beach at Scheveningen, a little window onto the North Sea, and then, perhaps, this is the smallest full figure self-portrait of Vincent that survives.

And then pages and pages carefully constructed, enriched with rhetorical strategies, metaphors, and descriptions: we imagine a man who, at a certain point in the day, feels the need to change mode of expression. After all, painting with colours or with words makes no difference, Zola and Balzac, for instance, are ‘painters of a society, of a reality as a whole’, he tells Theo. Even in his style so direct and without preambles, the tone he takes with his various correspondents is not always the same: with his ‘little sister’ Wil he feels free and also protective; with Van Rappard (who came from an aristocratic family) the tone is exquisitely that of artist-friends, print collectors; with the young Bernard he speaks openly of just about anything, from art to brothels, with Gauguin instead he is quite respectful, in French they use the formal ‘vous’. Nevertheless, as soon as ‘G.’ arrives in Arles, Van Gogh quickly writes to their common friend, Bernard, that in Gauguin ‘blood and sex have the edge over ambition’; then he goes on, speaking of his idea of ‘the painting of the future’; Gauguin adds a few lines to their friend who has remained in Paris. This letter of early November 1888 (exhibited for the first time, recently acquired by the Museum), is one of a kind, rich in meaning. The letters that came later between the three artists, a crucial debate on the future of art at the turn of the century, have sadly been lost for the most part.

Unlike his painter friends, for Vincent, a solitary man, a genius so melancholy he would eventually die of it, writing seems almost like a duty, a part of life, a part of his nature. It is this pressing need to analyse his choices, to discuss his take on situations with others, to bring his ideas into focus, and continually, there is the urgency to reflect on his duty as an artist of his time, a theme Vincent never ceased to question himself about. He knew well that the artist passes away but the artworks remain. As do his letters.

From the left: letter from Vincent to Theo, with sketch of The Sower, Arles, c. 21 November 1888; Vincent van Gogh, The Sower, oil on canvas, 1888, © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Vincent van Gogh Foundation.

Your Loving Vincent. Van Gogh’s Greatest Letters

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

9 October 2020 – 21 January 2021

The exhibition is accompanied by Vincent van Gogh. A Life in Letters, edited by Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten, a new anthology of Van Gogh’s letters, with authors’ commentary and illustrations of the original manuscripts and sketches. It is now more than a decade since the complete correspondence of Van Gogh was published by the Van Gogh Museum in collaboration with the Huygens ING, which was the result of many years of research, resulting in the six-volume edition of Vincent van Gogh – The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition (2009) edited by Nienke Bakker, Leo Jansen and Hans Luijten, both in print and in digitalized form at www.vangoghletters.org.

For more on the places where Van Gogh lived and worked see Living with Vincent van Gogh. The Homes & Landscapes that Shaped the Artist by Martin Bailey (White Lion Publishing 2019), and Sulle tracce di Van Gogh. Un viaggio sui luoghi dell’arte by Gloria Fossi, with photographs by Mario Dondero and Danilo De Marco (Giunti 2020, English translation in preparation). On Van Gogh’s readings see Vincent’s Books. Van Gogh and the Authors who Inspired Him by Mariella Guzzoni (Thames & Hudson 2020); for more on Giovanni Testori’s writings on Van Gogh, see Archivio Testori, and his introduction in Van Gogh. Catalogo completo dei dipinti, by L. Arrigoni and G. Testori (Cantini 1990).

Two more exhibitions on Van Gogh are currently running in Europe: Becoming Van Gogh, at the Didrichsen Art Museum in Helsinki (5 September – 31 January 2021), and Van Gogh. The Colours of Life, at Padua’s Centro San Gaetano (10 October – 11 April 2021).

(Translated from the Italian by Louise Fitzgibbon)

Since 2011

Since 2011