“Ah, my dear Theo, if you could see the olive trees at this time of year... The old-silver and silver foliage greening up against the blue. And the orangeish ploughed soil. It’s something very different from what one thinks of it in the north – it’s a thing of such delicacy – so refined. It’s like the lopped willows of our Dutch meadows or the oak bushes of our dunes, that’s to say the murmur of an olive grove has something very intimate, immensely old about it. It’s too beautiful for me to dare paint it or be able to form an idea of it.”

“… le murmure d’un verger d’oliviers”. These are the earliest lines we have describing Vincent’s feelings among the olive trees of Provence in Springtime. The scene is set in Arles, 28 April 1889, four months after the dramatic incident at the Yellow House with G., with Gauguin. A keen observer, Vincent instinctively knew how to immerse himself fully in nature. From a willow trunk on a road side he could create a portrait, indeed years before he had written to his brother that one must depict “a pollard willow as though it were a living being, which it actually is”, and that one mustn’t tire of working on it until there truly is “some life in it”. There were no olive trees in The Netherlands, this was the beginning of a Provençal love story.

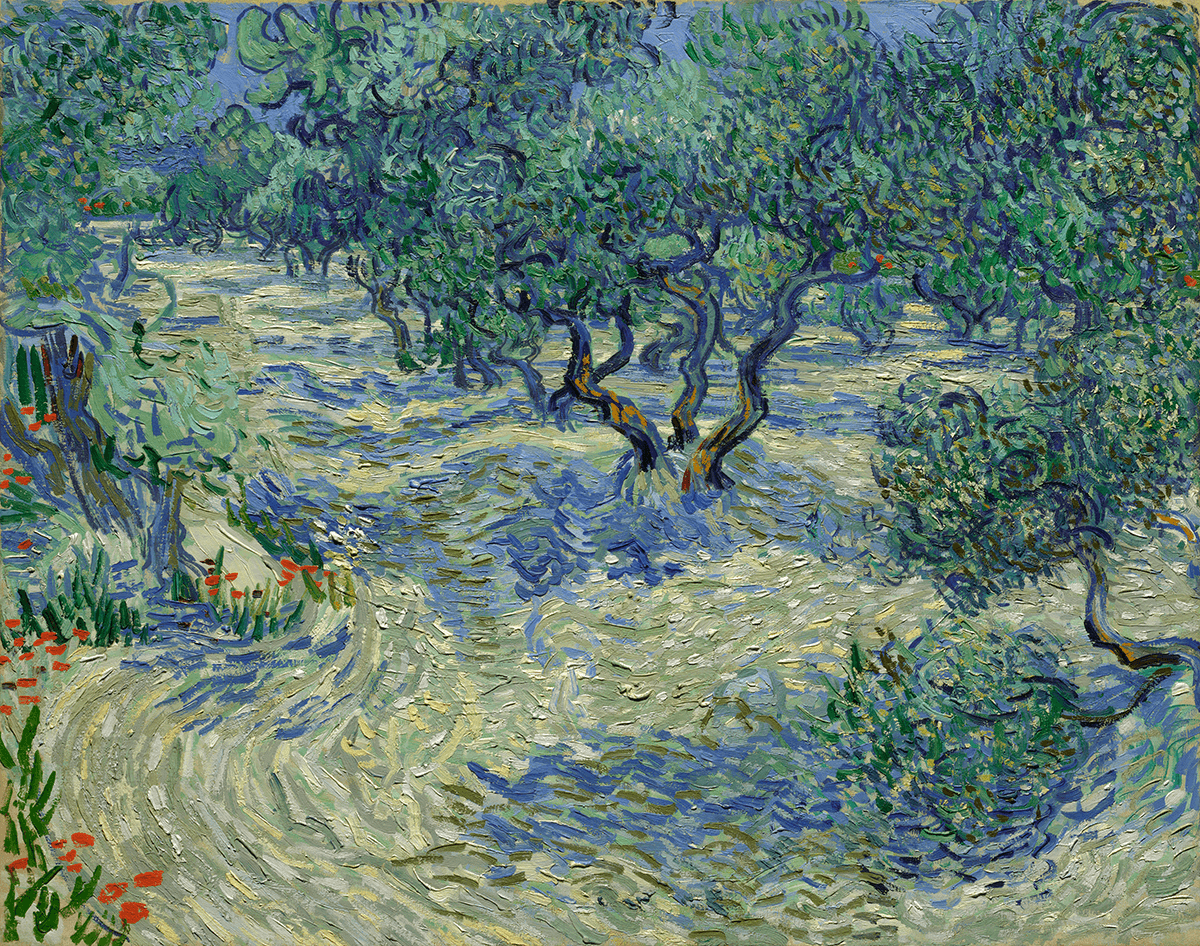

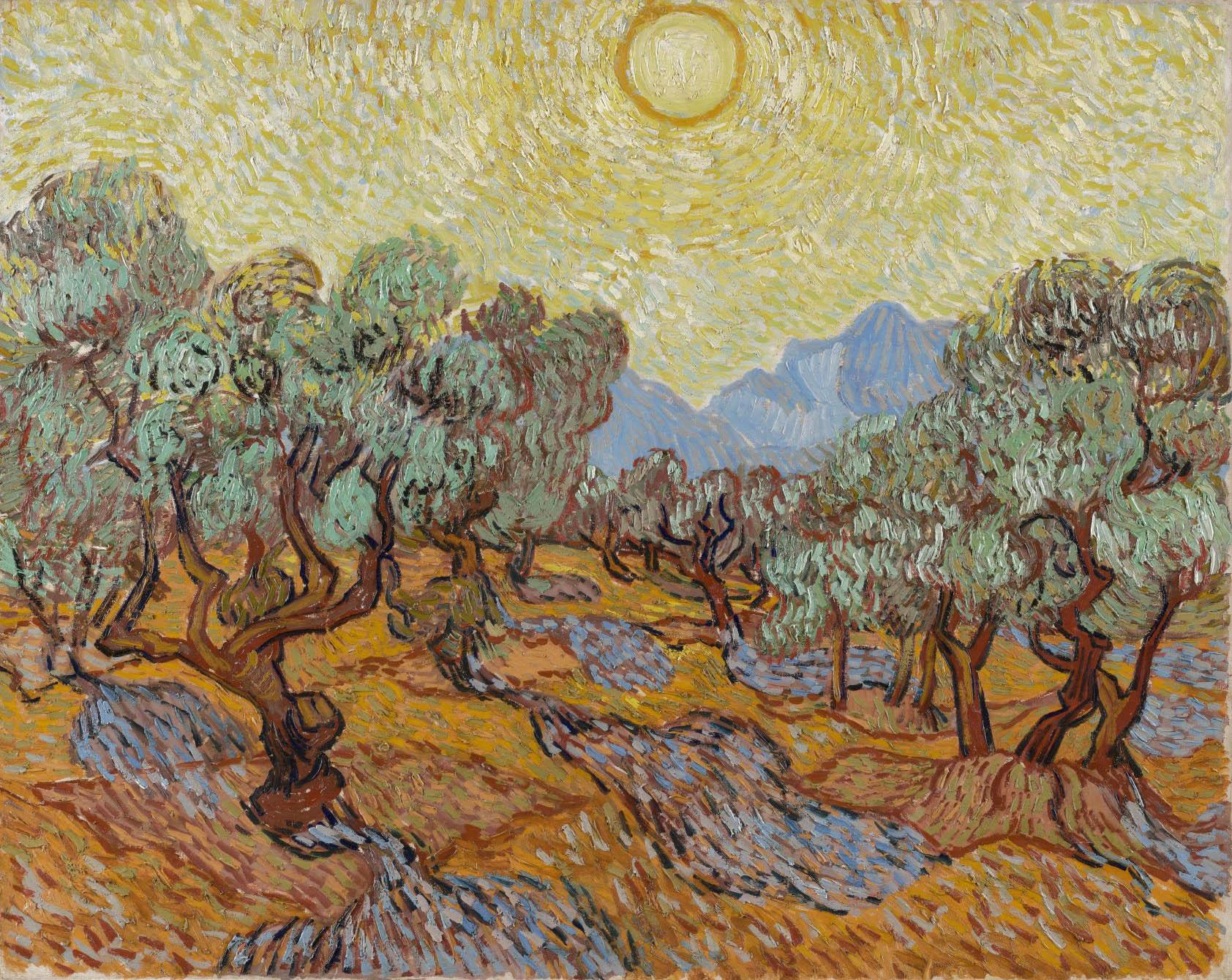

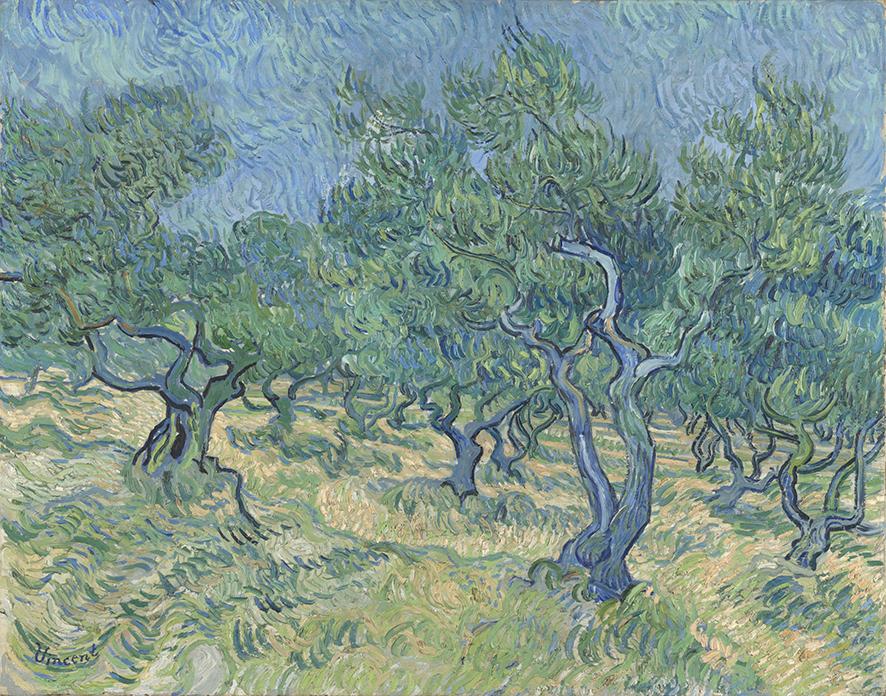

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June 1889, oil on canvas, © The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-2

Van Gogh and the Olive Groves is the title of the revealing new exhibition currently running at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (11 March – 22 June 2022) – the result of a collaboration between the Van Gogh Museum and the Dallas Museum of Art (where the exhibition was held until 6 February 2022). It marks the conclusion of a partnership project of curators Nienke Bakker (Van Gogh Museum) and Nicole R. Myers (Dallas Museum of Art), that has been under development for almost a decade. Vincent dedicated some fifteen canvases to the motif of the olive trees during his time in the asylum of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and today these are spread about various museums all around the globe. Lesser known, this important group of paintings has never been the focus of special study until now, nor exhibited together. This exhibition, and the scholarly catalogue that accompanies it (Van Gogh and the Olive Groves), are not only the first ever real examination of the significance of olive trees for Van Gogh, but also present the outcomes of an extraordinary scientific comparative study into all of the paintings of the olive grove series – a research-project that involved an international team of curators, conservators and scientists.

Not just olive trees

Van Gogh left Arles on May 8, 1889, and committed himself to the psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy de Provence, 25 kilometres north-east of there, beyond the Alpilles. We do not have a single oil canvas of an olive grove from his first year in Provence – “too beautiful for me to dare paint it” he had humbly declared in a letter dated a few days before, while he was preparing a large shipment of thirty works to be sent to Theo in Paris.

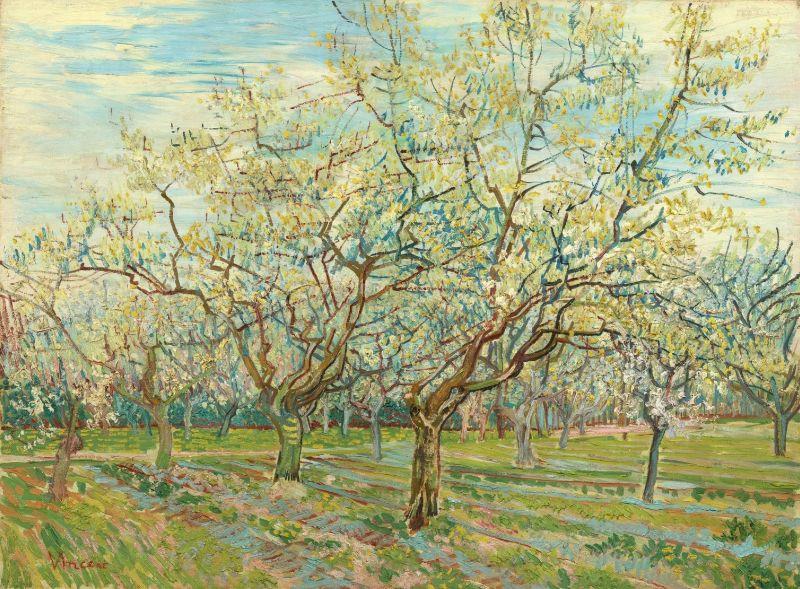

And yet, beholding the magnificent orchards in blossom that are displayed in this show, immortalised on canvas on his arrival in Arles in the Spring of 1888, he had had no hesitation. On the contrary, “In a fury of work”, he was enchanted when, “suddenly a tremendous wind began to blow” and there was “sunshine that made all the little white flowers sparkle”– an effect that he had “only ever seen here”. In those days, perhaps the happiest of his life, his only desire was to seize the moment.

Vincent van Gogh, The White Orchard, April 1888, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

This time the challenge before him was much greater: these are not just olives trees, his vision embraced the olive garden of Getsemane.

“The figure of Christ has been painted – as I feel it – only by Delacroix and by Rembrandt. . . . . . . And then Millet has painted . . . . Christ’s doctrine”, he wrote to his friend Émile Bernard in late June 1888, with dot dot dot elongated and spaced out like the dashes of a telegram, void of words. We know from his letters that he made two failed attempts in the Summer of 1888, when on his easel he had two oil studies of olives, “jardin des oliviers”, the first “with a blue and orange Christ figure, a yellow angel”, and “olive trees with purple and crimson trunks”, but then he destroyed everything. “I can’t, or rather, I don’t wish, to paint it without models”, he wrote to Theo.

It’s worth noting that his vision had many layers of meaning for him, beginning from his years with the Goupil galleries through to his religious period. In his iconographic ‘archive’ there was Corot’s The Olive Grove, with the dark olive trees in the blue dusk and “the evening star”– a painting which had “profoundly moved” him at age 22, at the Parisian retrospective of 1875. There were the many Goupil & Co. black and white reproductions of works that were famous at the time, such as Getsemane by Ary Scheffer or by Paul Delaroche, which Vincent collected and sent to his sisters. There were the verses of the gospel according to Luke, the only one who narrates the story of the visitation of the consolatory angel (Luke, 22:39-45). Indeed, in his religious period, Vincent had transcribed various passages from the Bible, including “Lukas XXII”, on a loose sheet of paper that has survived to the present day, believed to be from 1887, part of the Van Gogh Letters Project :“Then an angel appeared to Him from heaven, strengthening Him. And being in agony, he prayed more earnestly”.

![Vincent van Gogh, Detail of a loose leaf of passages copied from the Bible [RM10], probably February-March 1877. Courtesy and © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam](/sites/default/files/3.rm10-b1465v196vangoghmuseum.jpg)

Vincent van Gogh, Detail of a loose leaf of passages copied from the Bible [RM10], probably February-March 1877. Courtesy and © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

Engraved in Vincent’s mind however, there was also Delacroix, and above all Rembrandt: “he’s the only one who, as an exception, did Christs, &c. And in his case, they hardly resemble anything by other religious painters; it’s a metaphysical magic”, he wrote from Provence to his friend Bernard, underlining the word ‘only’. Rembrandt’s etching, Agony in the garden, with the angel rescuing Christ, had kept him company in his religious period, hanging on his bedroom wall in Laeken, beside its matching work, his beloved “La lecture de la Bible” (after The Holy Family at Night today attributed to the workshop of Rembrandt).

These were the images and words that were certainly still vivid within him during his walks about Arles, especially over the plains of the Rhône towards the rocky hills of Montmajour, where some olives grew. And yet the “metaphysical magic” of Rembrandt remained untouchable, he would not approach the subject for another year.

The olives of Saint Rémy: Summer 1889

Saint-Rémy, June 1889. When at long last, a month after his arrival in the clinic, Van Gogh was allowed to venture beyond those sad walls, he found himself among the olive groves, and was again enchanted. As can be observed in aerial photographs from some decades later, the area near the clinic was studded with olive trees, laid out in many neat plots, at the foot of the Alpilles.

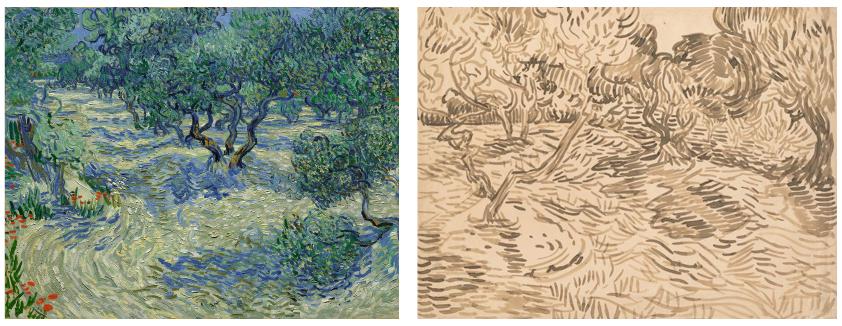

As Teio Meedendorp notes in his contribution to the catalogue, they were for the most part fairly young trees, about seventy years old: around the turn of the century there had been numerous cold spells which had decimated them. This is why, as Meedendorp points out, Van Gogh’s olives “tend to be short, thin and squat rather than large and thick”, as we see in what is currently believed to be the earliest canvas in the series (National Galleries of Edinburgh, below).

Very lively and with contrasting colours, this first painting is one of the best preserved of the group. Preceded by a large ink drawing (ca. 50×65 cm, like the painting), its vivacity is striking, not just because of its loud colours, but also because the brushstrokes are so alive and immediate, painted in a single session. Certainly the olives trees here, living beings both in the drawing and the painting, have much more than just “some life” in them.

From the left: Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June 1889, oil on canvas, © National Galleries, Scotland; Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, June 1889, brush and ink on paper, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

Between June and July 1889 Vincent dedicated four canvases to olive trees. In one of these (believed to be the third) he experimented with his stylised version in a painting most likely executed indoors, The Olive Trees (in New York at the MoMA, not on show). Simplification of lines and curves, almost abstract forms, “exaggerations from the point of view of the arrangement, their lines are contorted like those of the ancient woodcuts”, he told Theo. A study, he continued, “comparable in sentiment” to the to the Synthetist aesthetic developed by Gauguin and Bernard who right in those days were debuting in Paris in a collective exhibition held at the Café des Arts (café Volpini), at Champ-de-Mars, on the occasion of the Exposition Universelle.

An epistolary debate on the role of memory and the imagination in the artist’s creative process had been ongoing since the year before, when on 5 October 1888 Van Gogh had written to Bernard this lovely, untranslatable phrase “je mange toujours de la nature”: I am nourished by, I eat… nature, it is my nourishment. “Others may have more clarity of mind than I for abstract studies – and you might certainly be among them, as well as Gauguin and perhaps myself when I’m old. But in the meantime I’m still living off the real world. I exaggerate, I sometimes make changes to the subject, but still I don’t invent the whole of the painting; on the contrary, I find it ready-made – but to be untangled – in the real world”.

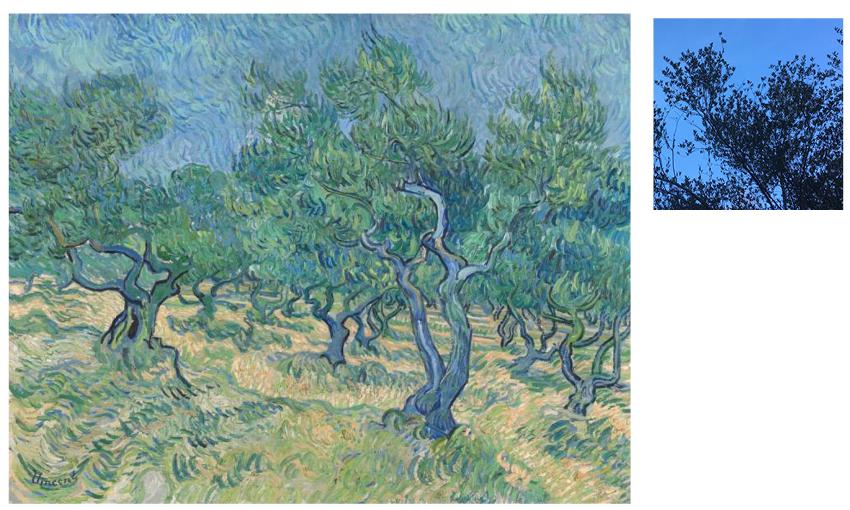

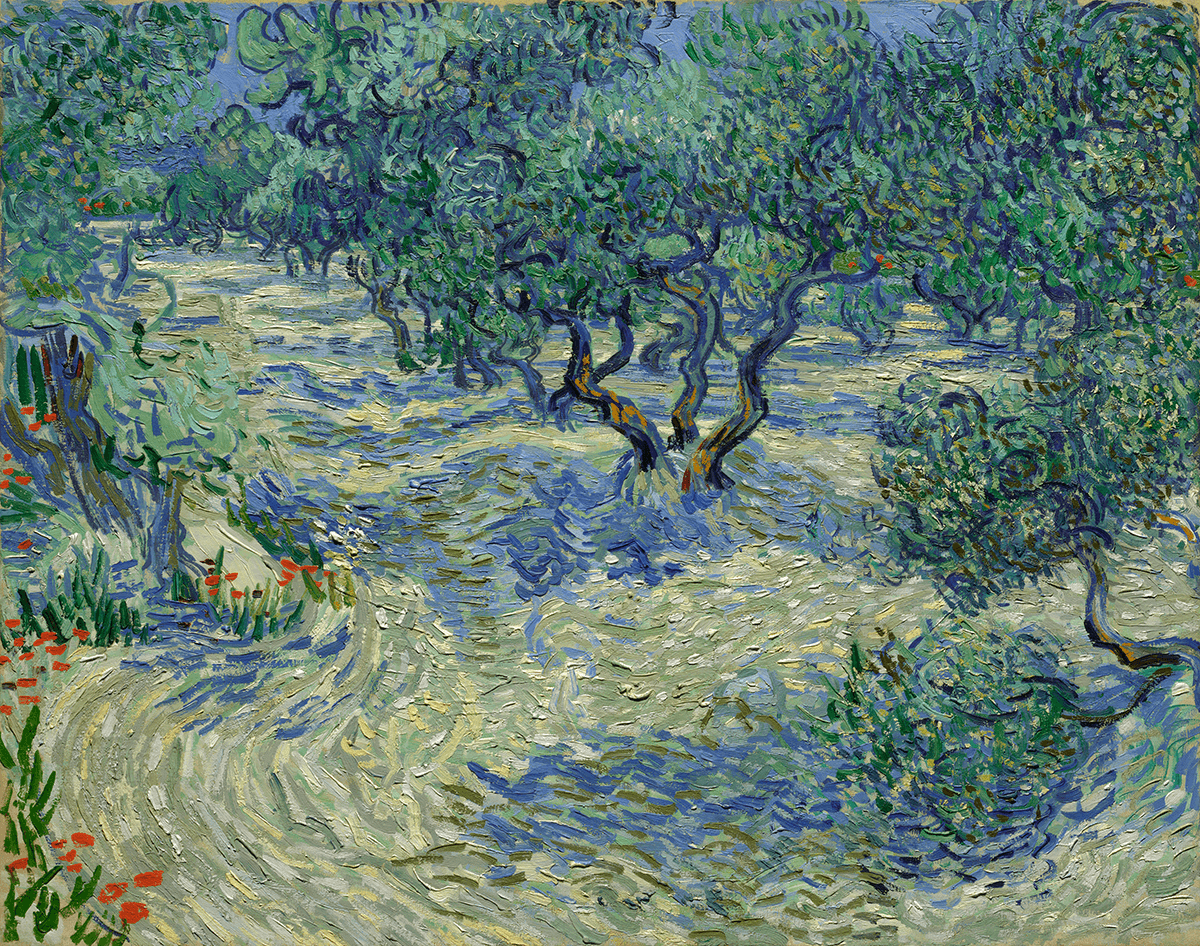

Van Gogh found his reply in reality, in nature, and he was soon back at work on a large canvas that would close the series of the Summer olive trees. Painted in July, in two painting campaigns, the first most probably en plein air, as we can tell from the traces of insects walking across the wet pigment. This time Van Gogh “tried to express the time of day when one sees the green beetles and the cicadas flying in the heat”.

Abandoning the plays on colour of the earlier canvases and putting aside stylisations, he concentrated on the effect, on the brushstrokes, proceeding in a continuous vibrant flow. And here we are in the midst of the olive grove listening to the murmur of the leaves which he paints as never before. His strokes turn upwards, forming rounded tufts, just like the individual leaves of this tree. The leaves of the olive are tough, they feel like leather to the touch. They have almost no stalk and turn up towards the sky, especially on the upper branches, as we can see in a photograph of an olive tree at dusk on our hills.

From the left: Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, July 1889, oil on canvas, signed ‘Vincent’ in the lower left, © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo; Olive tree, author’s photograph, detail

Van Gogh was a keen observer of every detail, translating each one onto canvas with a poetic simplicity so natural that it almost goes unnoticed. In a second phase, when the paint had dried, he reinforced the contours of the trunks and retouched the entire surface, adjusting the tones. He signed in the lower left, Vincent, following the arching movement of the brushstroke below it. The signature reminds me of Melencolia I in Dürer’s engraving which Vincent knew very well. This is the only signed painting in all of the series on olives – it is the only signature of this kind in all of his works.

The olives in Autumn

In early September Vincent was feeling very weak. He had suffered a new crisis that had lasted six weeks, the longest yet – which had occurred just when he “was already beginning to hope that it wouldn’t recur”. No work, no reading, not even a letter. After two self-portraits examining himself in the mirror, he dedicated himself to painting copies in colour after prints of his favourite artists; Christ in the Pietà after Delacroix has his own face. By the end of the month he summoned the courage to begin working outdoors, his mind returned to the olives, and he produced three new, smaller canvases. One of these, without sky, and painted in autumnal tones, irresistibly draws us into the embrace of the olive trees. We are invited to walk into the marvellous shelter of nature. Part of a private collection, this painting has not been shown for almost a century.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, September 1889, oil on canvas, private collection

“You have to work hard…” he writes to Bernard in early October. “Because it will be a question of giving strength and brilliance to the sun and the blue sky, and to the scorched and often so melancholy fields their delicate scent of thyme”. Vincent knows this Provençal motif is something new, not already explored, at least not thoroughly enough: “Well now, I’ve seen some by certain painters, and by myself, which didn’t render the thing at all. Those silver greys are like Corot first of all, and that, above all, hasn’t been done yet – while several artists have been successful with apple trees, for example, and willows”.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, November 1889, oil on canvas, © Minneapolis Institute of Art. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

A yellow sun floods the new canvas he creates in November, demonstrating a completely fresh approach in terms of composition and pictorial style. There is a sacred sun which enfolds, illuminates his resurrection, taking up the whole sky. For the first and only time in the series Vincent depicts a pruned olive in the foreground, which proudly displays its silvery mane under the warmth of the November sun. “A proud man brought low” perhaps here too, like this great tree with its hacked trunk that we see in the Garden of the Hospital (on show). In a clever interweaving of metaphors between shapes and colours, Vincent recounts the mysterious force of nature, suffering, salvation and regeneration.

This is his reply to his painter friends who “had driven” him “mad with their Christs in the garden, in which nothing is observed” as he confessed to Theo, adding ironically “friend Bernard has probably never seen an olive tree”. In November the debate starts up again, creates tension, Gauguin has sent him a sketch on the letter (on show), Bernard a photograph. “I believed that thinking and not dreaming was our duty”, Van Gogh snaps back, an obvious allusion to the Parisian context that he had left behind him, and to the works “in the style of Redon”– the dreamlike atmosphere that Vincent did not admire. His friends were creating “modern” biblical scenes, visionary works with concisely formed figures, offered as harbingers of a new truth, while referencing ancient iconography. These examples irritate him, giving him “an uncomfortable feeling of a tumble rather than progress”.

In fact, it is precisely because Vincent knows the Bible, and religious art like the back of his hand that he is able to go beneath the surface, “The Bible – the Bible – Millet was brought up on it from his childhood, used to read only that book and yet never, or almost never, did biblical paintings” he explains to Bernard, “… to give an impression of anxiety, you can try to do it without heading straight for the historical garden of Gethsemane; in order to offer a consoling and gentle subject it isn’t necessary to depict the figures from the Sermon on the Mount…”. ‘Consoling’, here, is a key word – art as consolation recurs in Van Gogh’s work. Interestingly, the debate between Gauguin and Bernard, crucial for the history of art, also had to do with artistic duty.

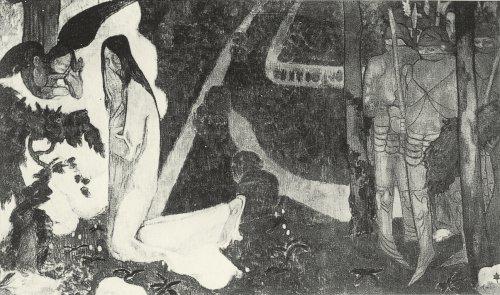

Émile Bernard, Christ in the Garden of Olives, 1889, photograph (present whereabouts unknown).

“Corot did a Garden of Olives with Christ and the star of Bethlehem: sublime. In his work you feel Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles too, sometimes, as well as the Gospels, but how sober and always giving due weight to modern, possible sensations common to us all.” (emphasis added), he continues, in the same long letter to Bernard. This is really where Van Gogh’s true strength lies, the only art possible for him is that which speaks to everyone, that connects everyone – art for “the common people” remains his creed. It is a strong, ethical-political position, especially if we consider the subjective reality and primitive exoticism that Gauguin pursued – the myth of evasion, wilderness, far from “rotten civilisation” – as he himself expressed it.

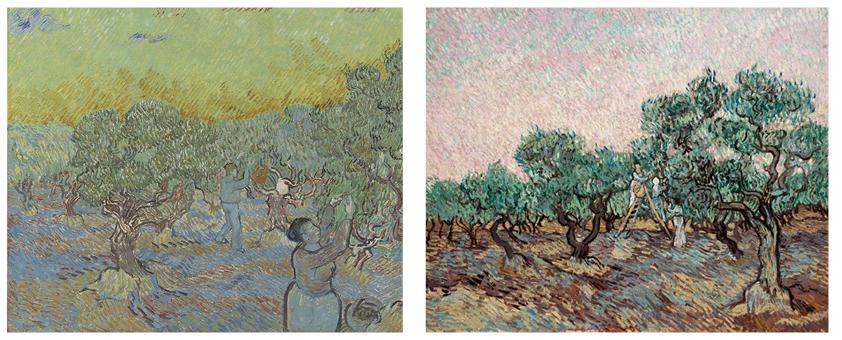

From the left: Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers, December 1889, oil on canvas, © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo; Vincent van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, November 1889, oil on canvas, © Basil & Elise Goulandris Foundation, Athens

Thus we can appreciate even more the series of the last canvases on the theme. In the first a male and a female figure enter the scene, harvesting olives, in the other (which he will repeat twice) we see the traditional ladder or ‘cavalet’, with three women intently harvesting. This is Nature, the circle of life, under ever wider skies – symphonies of yellows, reds, pinks, from dawn to dusk that cold December.

“If I remain here I wouldn’t try to paint a Christ in the Garden of Olives”, he had written a month earlier, “but in fact the olive picking as it’s still seen today, and then giving the correct proportions of the human figure in it, that would perhaps make people think of it all the same”. There is something immensely old about it.

Scientific research

Several sections of the exhibition are dedicated to the results of the research carried out on the fifteen canvasses depicting olive groves (almost all on show). There were many challenges to face, just think that the identification of some of the versions that Vincent described in his letters was still uncertain. Now however, thanks to the analytical approach to the canvas supports, such as canvas fibers, thread count, and ground type, researchers have solved this first puzzle. Being able to count on an accurate sequence and chronology is the concrete basis for any study.

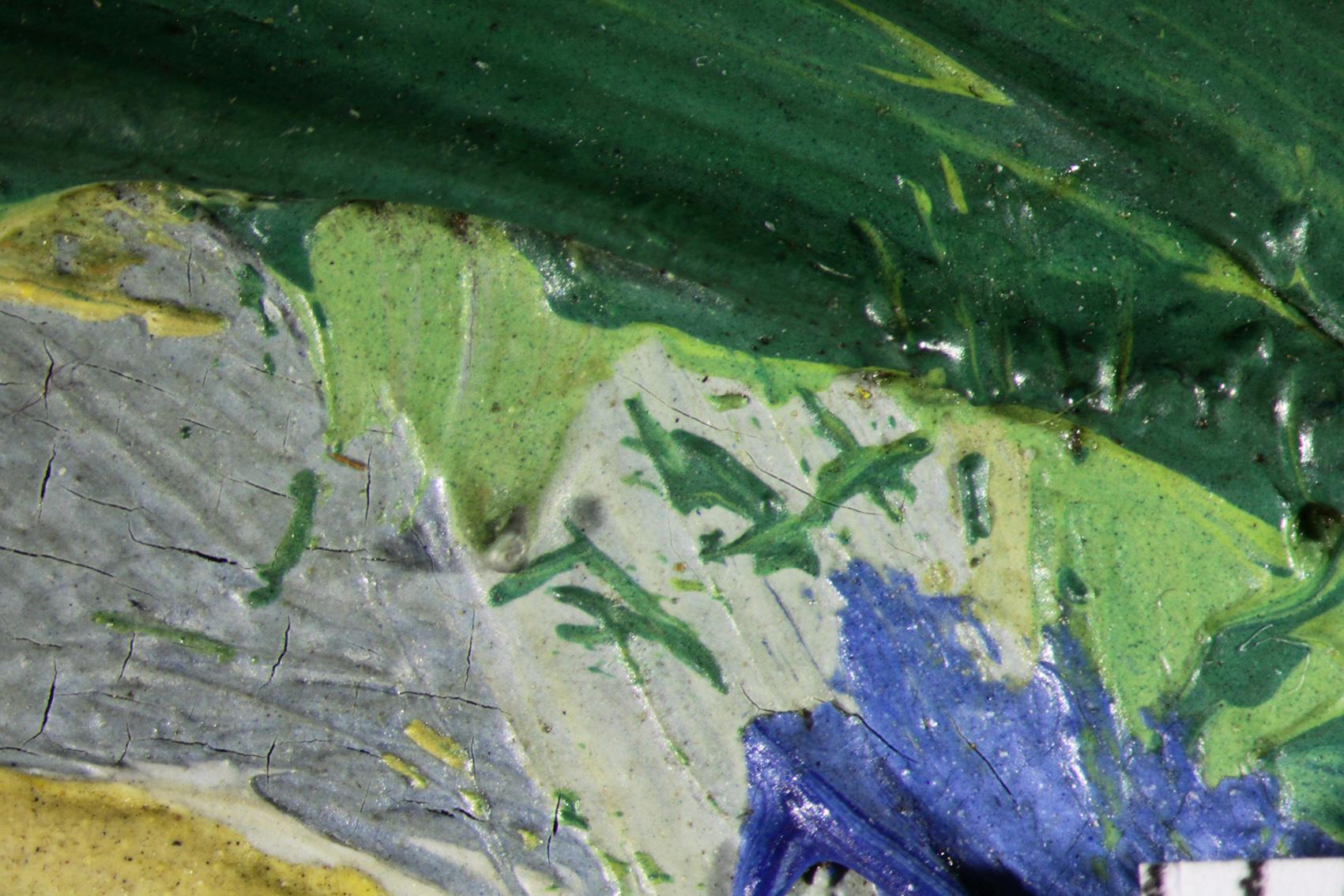

Grains of sand, seeds, blades of grass, insect foot prints or parts of insects trapped in the paint – all of this is proof of how much Vincent loved working en plein air. “During the technical photo documentation of the Olive Grove in our collection” as paintings conservator Margje Leeuwestein from the Kröller-Müller Museum told me, “our technical photographer Rik Klein Gotink drew my attention to this odd, very thin trace in the middle of the painting. When we realized that this trace was made by the legs of an insect walking on top of the still wet paint, for some 18 cm, we were very surprised. Especially when Kathrin Pilz, paintings conservator of the Van Gogh Museum, noticed another wider, coarser trace in the lower left part of the painting, caused by a larger insect, that left its prints, this time in green, from the adjacent, still wet pigment. This confirmed our idea that Van Gogh most probably painted the first phase of this work outdoors.”

Photomicrograph of traces of an insect walking in wet paint, in the middle of the foliage, in Van Gogh’s Olive Grove, July 1889 (illustrated above and signed ‘Vincent’). Photomicrograph by Margje Leeuwestein, © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Among the photomicrographs of insects or of brushstrokes, paint cross-sections, and the details of partly preserved colours hidden below the painting’s frame, we go exploring into the materials, supports, pigments and processes of Van Gogh’s work. These aspects, so important for a comprehensive study of his oeuvre, confirm once again the crucial role that museums have in conservation and in scientific research. According to Margje Leeuwestein, “the most difficult challenge during our Olive Groves research project was to compare the data of all the Olive Grove paintings, which are in different collections spread over the world. Fortunately, the research team, consisting of conservators, conservation scientist and art historians, was able to study the unframed paintings up close at the Van Gogh Museum, the Metropolitan Museum, the Museum of Modern Art and the Kröller-Müller Museum. It was an honour to be part of this interdisciplinary research project and an absolute treat to get to know these beautiful paintings by Van Gogh so well.”

Photomicrograph of traces of an insect walking in the wet paint, in the lower left corner of Van Gogh’s Olive Grove, July 1889 (illustrated above and signed ‘Vincent’). Photomicrograph by Margje Leeuwestein, © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

The question of colour and how it fades over time – a theme already analysed by the Van Gogh Museum with surprising results for The Bedroom – on this occasion again reveals critical points regarding some colours. The greatest problem is the fading of the red lake pigments, in particular geranium lake, an extremely light-sensitive organic red pigment, containing eosin. Too beautiful for Vincent to resist, he uses it abundantly: “You were right to tell Tasset that the geranium lake should be included after all, he sent it, I’ve just checked”, he wrote his brother from Arles, continuing and heavily underlining: “all the colours that Impressionism has made fashionable are unstable, all the more reason boldly to use them too raw, time will only soften them too much”.

Indeed, when Van Gogh writes of purple, red and pink tones – diligently describing the colours of his progressing works – often these colours no longer match what we see today. Almost all of the canvases in the olive tree series have suffered to a certain degree. As Kathrin Pilz and Muriel Geldof point out in their contribution to the catalogue, “The extensive application of geranium lake and two variants of cochineal in some of the works – pure as well as in a large number of mixtures with other pigments in various ratios – and their discoloration as a result of exposure to light have resulted in major colour shift and altered contrasts”. Vincent loved to make use of these bright pigments to obtain more vividly contrasting tones – as he did for the earth or for the skies. Thus, for example, the blue shadows of the olives with red blossoms (Kansas City, the first illustrated), would have been violet and, as he wrote: “their cast shadows violet”; the skies of the final canvases of December were initially more intense in the pinks and the reds (Otterlo, Athens, illustrated above, and recreated in the exhibition), following a very precise artistic colour scheme – yellow-violet, red-green, blue-orange. And so we are stunned to realise that the “arbitrary colourist” that he wanted to be was, in reality, even more audacious then we perceive today.

A triptych of the mind; “Reminiscences of Provence”

Van Gogh often thought of his works in pairs, in triptychs, or multiples like a “kind of ensemble”, as we see in his sketches scattered among his letters to Theo. The olive grove, a vitally important theme for him from the artistic and from the human standpoint, is no exception. At least in his mind. At the centre of this triptych was his great favourite, books and reading, in a luminous bookshop that he never got to paint. One the one hand the olive trees, perhaps just those he signed, and on the other a wheatfield. Let’s try to imagine it – it’s not so hard. In a symphony of greens, pale blues and yellows, a light in the shadows. Rembrandt’s diptych, “La lecture de la Bible” and Agony in the Garden, the matching set of prints that kept him company from his bedroom walls in Laeken, seem to return here like an eternal beacon, in modern key:

“I keep telling myself that I still have it in my heart to paint a bookshop one day with the shop window yellow-pink, in the evening, and the passers-by black – it’s such an essentially modern subject. Because it also appears such a figurative source of light. I say, that would be a subject that would look good between an olive grove and a wheatfield, the sowing of books, of prints. I have that very much in my heart to do, like a light in the darkness”, he wrote to Theo in late November 1889, when he was still working on the olive trees.

Vincent van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, May-July 1890, Pencil on paper in sketchbook, courtesy and © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

On 20 May 1890 Van Gogh left Saint-Rémy, and moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, some thirty kilometers from Paris. In his last sketchbook, a small notebook of 13×8 cm, he dedicated some pages to a group of images after his Provençal paintings, drawn from memory. It’s rare to see these little treasures, so delicate and fragile, they are very rarely exhibited. His idea was to create an album of engravings that he could print on Dr. Gachet’s press – “Reminiscences of Provence”, and give to friends. Among sketches after his Irises, Sunflowers, The Ravine and Les Alyscamps, there are also Women Picking Olives – a sign of the importance he attached to his final painting, on this beloved Provençal motif.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, July 1889, oil on canvas, © Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

11 March – 12 June 2022

Further reading:

The exhibition catalogue, Van Gogh and the Olive Groves, is edited by Nienke Bakker (Van Gogh Museum) and Nicole R. Myers (Dallas Museum of Art), with essays by Nienke Bakker, Teio Meedendorp, Nicole R. Myers, Kathrin Pilz and Muriel Geldof, Louis van Tilborgh (Yale University Press, 2021). For more on a comparative, scientific study on the three versions of The Bedroom by Van Gogh, see Van Gogh’s Bedrooms, edited by Gloria Groom (Yale University Press, 2016). Among recent books: Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame, by Martin Bailey, a definitive account of the final days of Van Gogh’s life (Frances Lincoln, 2021); Through Vincent’s Eyes. Van Gogh and His Sources, edited by Eik Kahng, with contributions by Todd Cronan, David Misteli, Rebecca Rainolf, Rachel Stokowsky, Sjraar van Heugten, Marnin Young (Yale University Press, 2022).

- The exhibition Van Gogh. Self-Portraits, curated by Karen Serres, is currently running at The Courtauld Gallery in London; it’s the first show devoted to Vincent’s self-portraits across his entire career (3 February - 8 May 2022).

(Translated from the Italian by Louise Fitzgibbon)

Since 2011

Since 2011