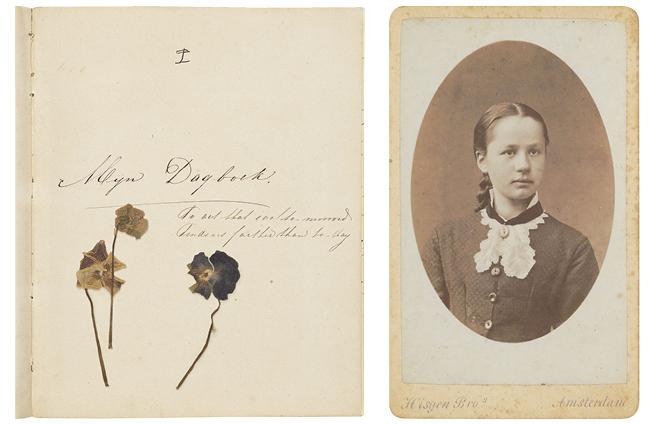

‘Today I begin my diary. I used to laugh at anyone who did it, for I thought it foolish and sentimental […]. For in the routine of daily life there is so little time to reflect, and sometimes days go by when I don’t actually live, but let life happen to me, and that’s terrible. I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life: “I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble,” and yet I believe that something like that could happen’. Amsterdam, March 26th 1880, Jo Bonger is seventeen years old. This is the first page of her diary, ‘Mijn Dagboek’, to which she will entrust her musings on and off until 1897. For the title page of this first notebook she chose to transcribe two lines from the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, ‘To act that each tomorrow/find us farther than today’. These words would become her motto for the rest of her life.

From the left: Jo Bonger, Diary n. 1 (1880-1881, 20,5 x 16,6 cm), © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam; Jo Bonger, ca. 1880-1882, Friedrich Carel Hisgen, photograph, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

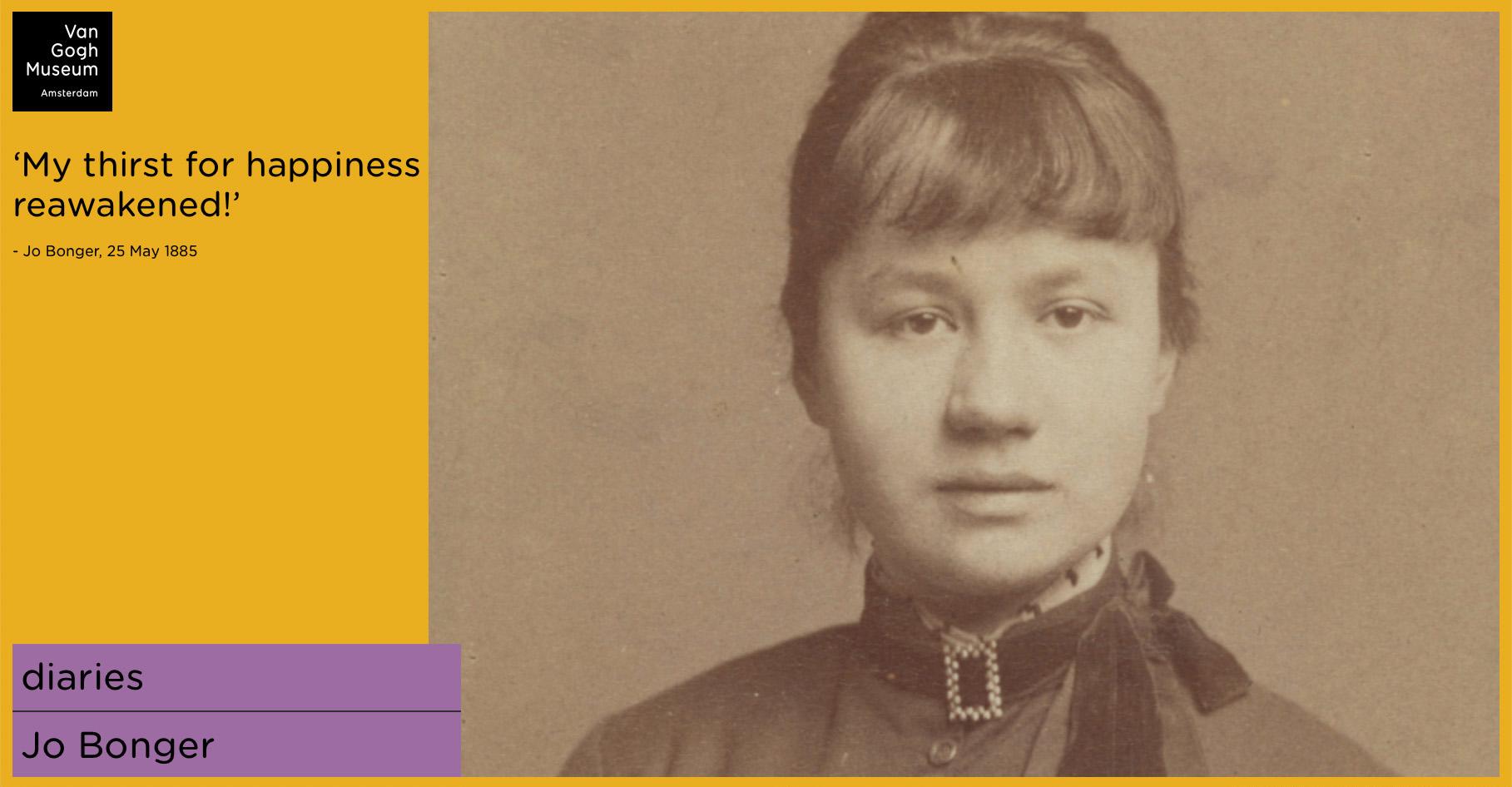

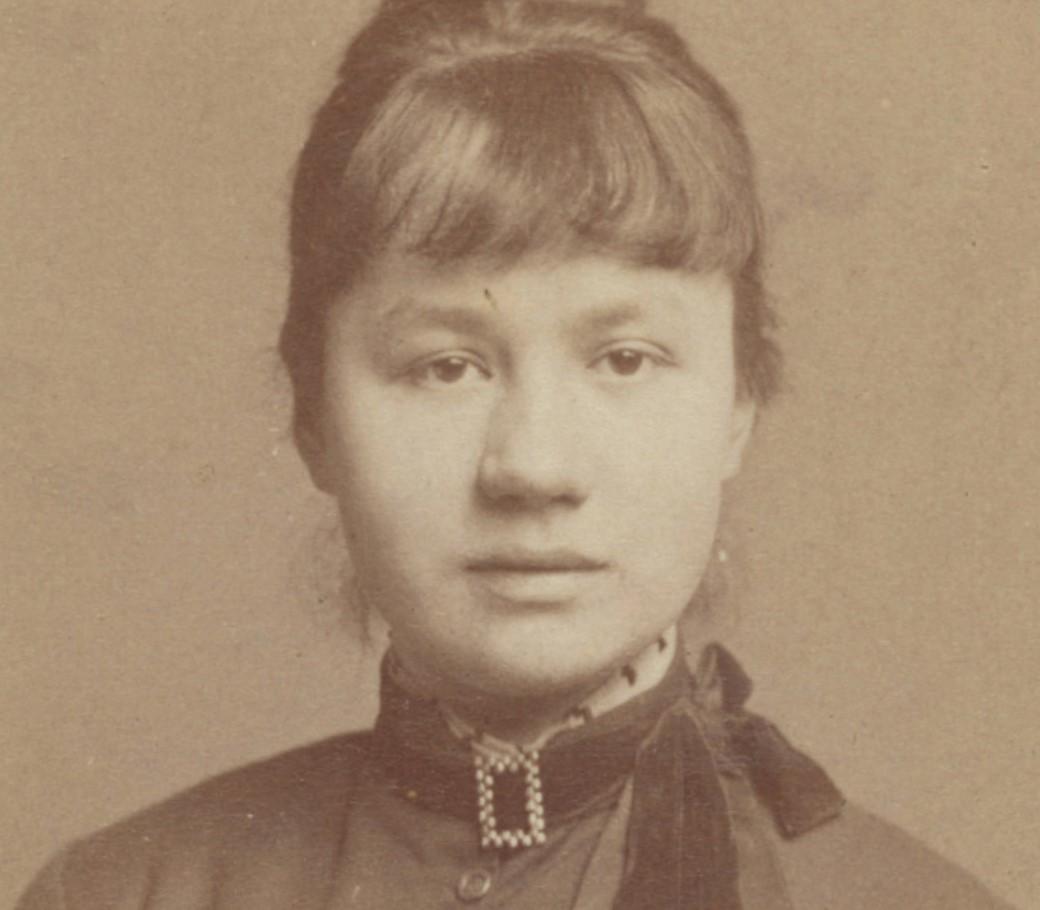

Little known but highly influential: Jo van Gogh-Bonger (1862-1925), wife of Theo and sister-in-law of Vincent van Gogh. Over 500 pages in four unpublished diaries, which from this September 18th can be read in English in the digital version edited by Hans Luijten, senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum (bongerdiaries.org). Enriched with annotations, references and precious insights, the diaries dive into the world of the thoughts, doubts and aspirations of a young girl at the turn of the century.

Like many of her contemporaries, Jo was determined to explore her own emotions, melancholies and joys through writing. Born in Amsterdam to a middle-class family, she became an English teacher early in life. She adored music, theatre and especially literature. She was an admirer of George Eliot whom she considered a ‘superior woman’; and devoured Anna Karenina, certainly in French (diary 3, pp. 34). A poetry-lover too, she enjoyed a moving visit to the Poet’s Corner of London’s Westminster Abbey and was struck by the sight of Dicken’s simple grave (diary 2, p. 23). The second diary was written almost entirely in English, while Jo was spending a few months in London to perfect her command of the language (July-September 1883). She read piles of books, Byron, Carlyle, Dickens among others, and often went to see plays. She saw Sarah Bernard on stage in Fedora, but was not impressed: ‘She is a beautiful woman, splendidly dressed; she is languissante, charmante, but not full of “high art” as I should like to call it’ (diary 2, p. 9). There was no doubt in her mind, the French actress would never be a role model for her.

After a romantic entanglement that didn’t work out, Jo accepted the courtship of Theo van Gogh. She was 26 at the time, and he was a friend of her brother Andries. Lovestruck, they quickly got married and set up house in Paris. For three years she did not keep a diary, but we still have the letters she exchanged with Theo (Brief Happiness) and, soon afterward, with Vincent. She experienced her marriage as ‘the most beautiful one can dream’, she later wrote (diary 3, p. 137). There were tragic moments too though, like Christmas Eve 1888, when Theo rushed to Arles: Vincent had cut off his ear and been hospitalised. Less than two years later, at the end of July 1890, Vincent would commit suicide, shooting himself twice in the chest. Six months on, January 25th 1891, Theo also passed away, leaving her with their baby, named Vincent after his uncle. At 28, Jo suddenly found herself alone in the Paris apartment surrounded by a colossal burden. Hundreds of paintings, not just hung on the walls but stuffed under beds, thousands of drawings by a virtually unknown artist, piles of letters, and a child, whose first birthday fell just a week later, on January 31st.

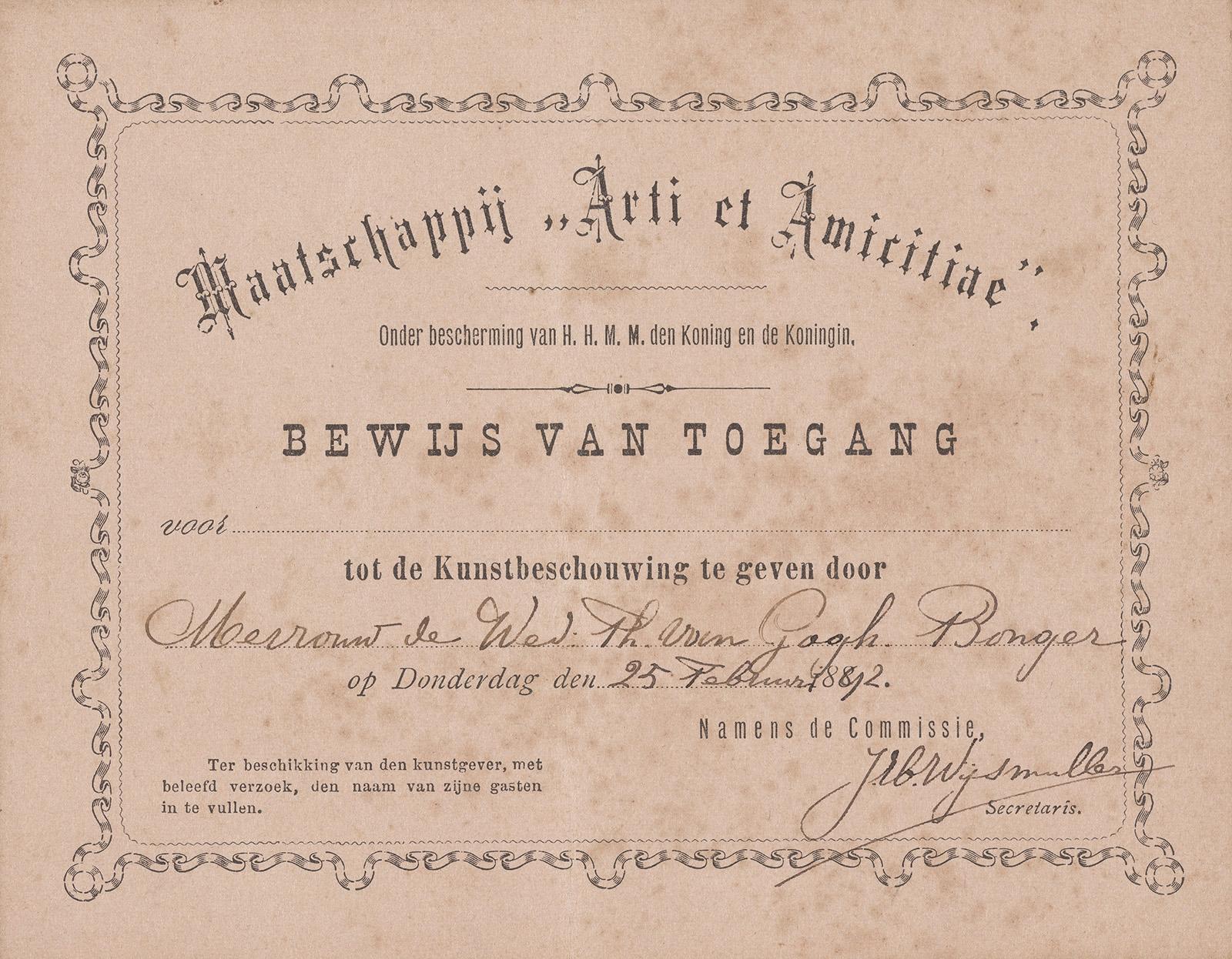

She returned to Holland as a young widow in late November of that same year. She took-up writing again to find some moments for ‘self-analysis and self-examination’… ‘I must use all my strength to learn again so that I may be of some use to my boy’ (diary 3, pp. 138-39). Vincent was her ‘little angel’. She opened a boarding house to ‘earn a living’ for both of them, Villa Helma, in Bussum, which was a lively cultural hub not far from Amsterdam. There she would begin to weave together a web of contacts, working like an industrious spider, as Luijten describes her: critics, painters, writers – anyone who could help her to gain recognition for Vincent’s work in a country which had so far shown no appreciation for his genius. After just three months back in Holland, February 1892 saw Jo eagerly awaiting the public’s reactions to the ‘art appreciation session’ held by Arti et Amicitiae, an influential artist’s group based in Amsterdam. The secretary Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller, had asked Jo to loan some of Vincent’s drawings for this event-exhibition dedicated to him. We don’t know if Jo spoke during the evening, her diary doesn’t mention it. ‘She always kept her personal ticket carefully’ says Hans Luijten, author of the first ever detailed biography of her ‘multifaceted life’, Alles voor Vincent (in Dutch; an English translation is in preparation, All for Vincent. The Life of Jo van Gogh Bonger). The day before the event she wrote in her diary: ‘The art appreciation session on Vincent’s drawing is in Arti tomorrow evening. – I have high hopes – I have a feeling of indescribable triumph when I think that it’s finally arrived – the appreciation – the liking – I must go to hear what people are saying – what their attitude is. The ones who used to ridicule Vincent and call him a fool.’ (diary 4, p. 2). Her struggle was great, especially in the 1800s which were so heavily dominated by men – just think of George Eliot (one of Jo’s favourite authors), who used a male pen-name and hid her gender in order to be taken seriously. In the Netherlands things weren’t much different, Jo was not ‘Jo’, but instead the widow of, as it was customary at the time. The original admission ticket signed by Wijsmuller reads ‘Mevrouw de Wed: Th. Van Gogh Bonger’, literally ‘Miss the Widow: Th. [Theo] Van Gogh Bonger’. Embattled and resolute, she did not retreat when her determination and passion for Vincent’s revolutionary work was taken for petulance, fanaticism or even incompetence (diary 4, p. 21).

Admission ticket from Jo van Gogh-Bonger for the art review at Arti et Amicitiae, 1892, Amsterdam, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

Working tirelessly from 1882 to 1900, she managed to coordinate some 20 highly strategic exhibitions around Holland, displaying Vincent’s great masterpieces alongside his minor works. Thus, she was able to progressively build recognisability for his oeuvre. This tactic was successful, for each exhibition she got articles published in the Dutch newspapers in a country where, she wrote: ‘people are not so generous as far as Vincent’s work is concerned’ (diary 4, p.2). This gave her a sense of fulfilment and serenity. In 1905, when at last she felt the moment was ripe, she organised the largest show that has ever been held to date: she rented the galleries of the Stedelijk Museum of Amsterdam, where she presented no fewer than 484 of Van Gogh’s works – ‘an exhibition of this magnitude would never again be matched’, says Luijten. She continued with the same strategy abroad, especially in Germany, through influential art dealers like Paul Cassirer. By 1914, about 150 of Vincent’s works were found in German public and private collections, strongly influencing the emergence of modernism in Germany (at the centre of the exhibition open at the Städel Museum of Frankfurt). Careful not to over-saturate the market, in a 34-year period Jo sold or donated about 192 painting and 55 drawings, leaving the majority of the collection to her son, who would continue her mission.

Her fourth diary, which sadly ends on May 8th, 1897, tells of a young woman, both progressive and conflicted. On one hand lay her motherly duties and the monumental task of ‘keeping all the treasures that Theo and Vincent had collected intact for the child’. On the other hand was her highly independent spirit, her desire to be a woman – free to live and free to love… Five years after Theo’s passing she had a relationship with the painter Isaac Israëls, which she chose to end at a certain point, ‘I don’t want to play with fire’, she wrote; but in the final pages of her diary she confesses, ‘oh, if I was free and independent – how I would give myself to him – how he would enjoy my beautiful young body – how I would stand free and pure before him – no egoism […] But I may not, if I did – I would make it impossible to earn for the child – so it’s better that we don’t see each other for the time being’. (diary 4, p. 98). Isaac painted the boy’s portrait, little Vincent, and Jo cherished it.

![From the left: Isaac Israëls, ca. 1888 (Joseph Jessurun de Mesquita [attributed to], photograph), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Isaac Israëls, Portrait of Vincent Willem van Gogh, 1894, oil on canvas, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam](/sites/default/files/3.israels_vwvg.jpg)

From the left: Isaac Israëls, ca. 1888 (Joseph Jessurun de Mesquita [attributed to], photograph), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Isaac Israëls, Portrait of Vincent Willem van Gogh, 1894, oil on canvas, © Van Gogh Museum, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Amsterdam

With a life full of passions and a free spirit, Jo was also active in the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP, the predecessor of the Labour Party). The party had a branch in Bussum, and she participated vigourously. A staunch defender of women’s rights, in 1915 she travelled to Switzerland to attended the International Socialist Conference for Women’s Peace in Bern; in 1917, while in the USA, she went to a conference given by Leon Trotsky. Wealth was of no interest to her. She had a sole mission: to make Vincent’s work known to the world, and complete the task her husband had only just begun. She succeeded in the endeavour using her strategic intelligence: first the works, then the letters to Theo, which, after years of transcribing, she published in 1914, in both Dutch and German. ‘She had a mission. To get Vincent’s work known first, and then the letters. She followed this order’, says Luijten.

She died in 1925, at 63. Just over a year had passed since she had sold the Sunflowers to one of the most prestigious public collections in the world, the National Gallery of London, ensuring global visibility for Vincent. Two years before she died, she summed up her life in a letter to the French art critic Gustave Coquiot, bringing us back to the words with which she began her first diary: “It’s lovely, at the end of my life, after so many years of indifference and even hostility from the public towards Vincent and his work, to feel that the battle has been won”.

A digital edition of Jo’s diaries, bongerdiaries.org, was launched by the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam the 18 September 2019, together with the publication of the first biography of Jo, written by Hans Luijten, the result of ten years of research, Alles voor Vincent (Prometheus 624 p., in Dutch; English translation All for Vincent. The Life of Jo van Gogh Bonger). On the first floor of the Museum a themed wall has been installed for two months, presenting Jo’s crucial role in raising awareness of Van Gogh’s work.

Note: The exhibition Making Van Gogh. A German Love Story, at the Städel Museum of Frankfurt, is dedicated the posthumous reception and influence of Van Gogh’s work in Germany (23 October 2019 – 16 February 2020).

(Translated from the Italian by Louise Fitzgibbon)

Since 2011

Since 2011