On September 8, 1981, Ettore Sottsass and Barbara Radice roll up in a taxi a the Design Gallery in Milan. They’re excited and a little scared. That afternoon was the launch of an exhibition of a group of designers who had got together the previous December in their apartment and called themselves Memphis: Martine Bedin, Aldo Cibic, Michele De Lucchi, Matteo Thun and Marco Zanini. They rub their eyes in disbelief as more than 2000 people crowd the showroom to see 31 pieces of furniture, three clocks, ten lamps and eleven ceramic pieces.

The crowd spills out into the street, blocking the traffic. Sottsass and Radice have no idea what is going on. They think there must have been a road accident. No design event has ever attracted a crowd like this, and nobody can tell them how so many people came to be there that day. The invitation to the private view was a T-Rex with his toothy mouth wide open and his eyes sharply focused. A suggestion of things to come, a provocation almost. Will Memphis devour modern design? That day in September, 1981, the founding father of the new movement reached the acme of his success and popularity.

Ettore Sottsass was born in Innsbruck in 1917, towards the end of World War One. His mother was Austrian and his father from Trento, an architect who named him after himself, with the unusual addition of ‘Jr.’. Memphis lasted only five years before Sottsass left the group despite its huge success, with over 400 articles devoted to the designers in newspapers and magazines. Acclaimed and persecuted as a celebrity, the object of media scrutiny just as newspapers and magazines started to extend their range to art, design and show business, Sottsass decided to cut himself off from Memphis in 1985, bringing the fabulous 1980s to an untimely close just as the decade was reaching a turning point.

The main focus of the packed exhibition, its totem, was a Carlton bookshelf. Designed by Sottsass, it comprised brightly painted wooden shelves stacked horizontally, vertically and diagonally to look like a human figure, arms up in the air and legs wide open. The lower part of what looked like a primitive altar, comprised diagonal shelves sticking out on both sides, and a set of drawers resting on a black and white rectangular platform. The Carlton bookshelf became the centerpiece of the Memphis group.

Carlton bookshelf, 1981

It cannot be called a movement because there was never a founding manifest and there was never meant to be one. There was no explicit program, but simply a promotional campaign, press releases, a book and several exhibitions in quick succession, marking the irresistible rise of what was later defined as the Italian postmodern movement. The name Memphis came from the title of a song that was on the gramophone in the apartment as the group decided to form: Bob Dylan’s Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again (Blonde on Blonde, 1966). “OK,” Sottsass must have said. “let’s call ourselves Memphis.”

Bob Dylan featured in a photo Sottsass took in 1965 in San Francisco, alongside Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, and Peter and Julian Orlovsky. This was when the designer used to hang out with members of the Beat generation, together with his wife, Fernanda Pivano. In 1981, the year of his triumph, Sottsass was 64 and had already had a long career, starting in Turin in the 1940s where he worked with the founding father of social architecture at the Olivetti factory, surrounded by prototypes of computers, typewriters, calculators and publicity messages. Sottsass’s unique and original career path has recently been reconstructed in a coffee table book edited by Philippe Thomé called simply Sottsass (Phaidon Electa, 2014).

Who was Ettore Sottsass, and what role did he have in the world of international design? In the opening essay, ‘Design: the path towards Memphis’, Francesca Picchi argues that Sottsass was the first designer to claim a role as an intellectual, staking for himself a kind of freedom to move inside, around and outside the industrial culture from which his designs inevitably stem, despite their highly artistic flair. Sottsass’s career started out in the field of architecture, then moved towards fine art and painting, and then went on to find expression in the privileged world of Olivetti, the industrial leader of the 1950s. His career path reached its zenith when he carved out an autonomous role as designer and invented a field of action where the nineteenth century heritage of form and function gave way to a new sensorial esthetic. Comparing his work to a designer of his generation such as Dieter Rams, who worked with the German industrialist Braun, it soon became clear the extent to which Sottsass’s work was more visionary and poetic, and at the same time more critical. It could perhaps be said, after reading this book, that Ettore Sottsass’s greatest achievement was Ettore Sottsass himself. His ability to re-invent himself constantly, change strategy, adjust tactics, and make U-turns in order to make himself what he probably already was – that is, an artist determined to live the adventure of his life intensely. Francesca Picchi writes that design is a “discipline that tends to wonder what man’s destiny is in the context of industrial civilization.” Designers are forced to measure themselves against the yardstick of this innovative but often destructive force that is implicit in the industrial transformation of their life.

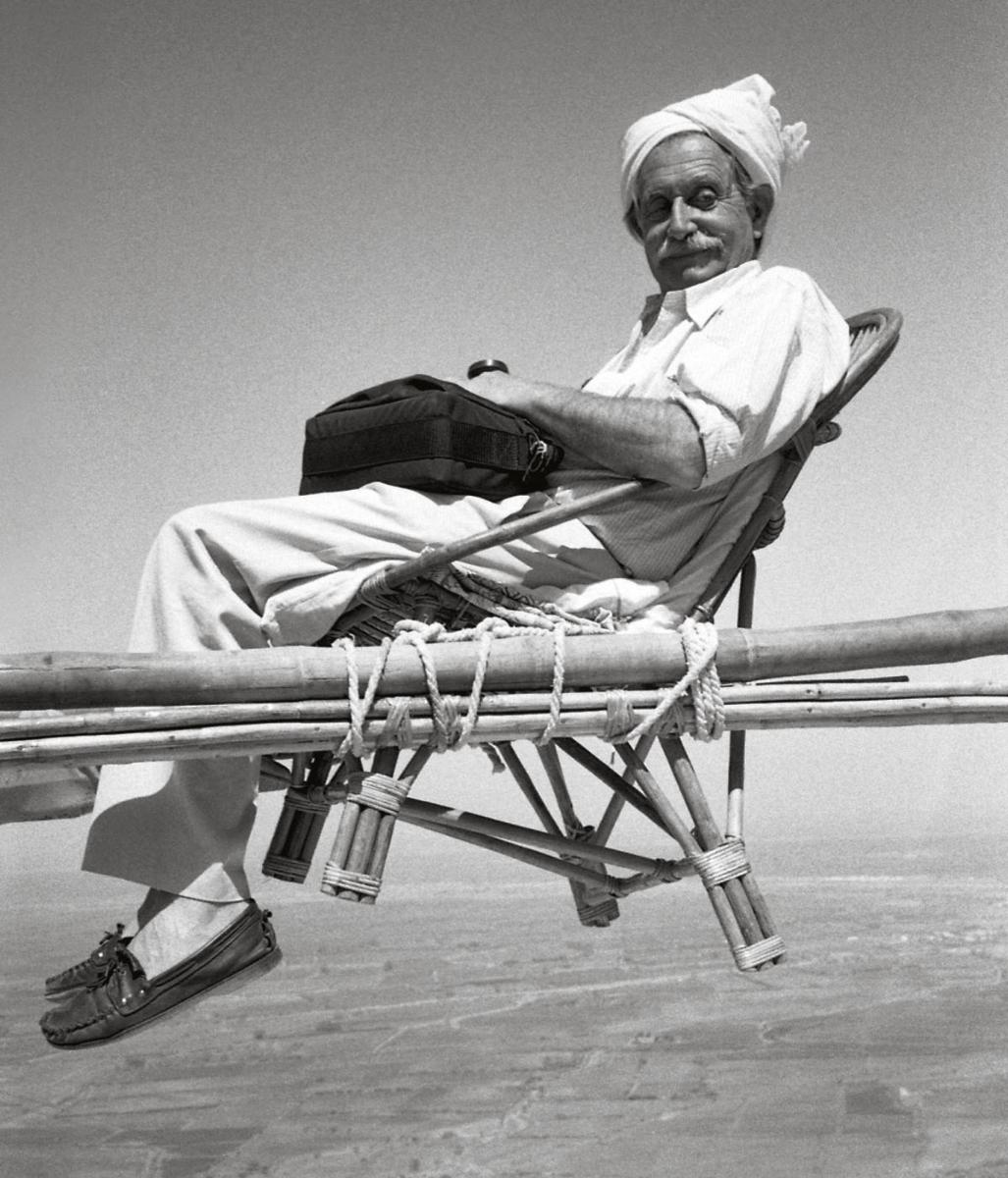

In his way, Sottsass was at the margins, even though he occupied a central position at a focal point of this transformation. He was at the margins because, year after year, he shifted the very idea of design, taking it back both to its pre-industrial, artisanal beginnings and to its artistic roots. His pieces lived in the middle, and Sottsass widened the space there, inhabiting the in-between that has always existed in design. Perhaps his Austrian origin played a role, as well as his love for Biedermeier, his father’s draftsmanship, his years at the Turin Polytechnic, his mingling with the artist Luigi Spazzapan, his fundamental hedonism, his quest for beauty, his belonging culturally to the experience of the 1930s, post-Fascism and post-ideology, his love for objects and for paper, his profound melancholy. Photographic portraits of Sottsass are highly revealing in this regard, as the recent book by the photographer-philosopher Giuseppe Varchetta shows (Ettore Sottsass, Tornano sempre le primavera, no? Johan & Levi, 2013). His difficult pursuit of happiness emerges clearly too in his masterful and literary autobiography, Scritto di notte (Adelphi, 2010). For all these reasons and many more, Ettore Sottsass is one of the most interesting characters on the Italian and international design scene, alongside two others: Bruno Munari and Enzo Mari. This trio of very different personalities and styles all converged towards a non-functionalist idea of design.

The book traces Sottsass’s life-path with profiles about his work and images from his and Barbara Radice’s archive. Barbara is the force behind the book, his biographer, wife and partner, collaborator and observer of the artist’s whole life’s work. The book starts with the sudden death of Sottsass’s father in October 1953, after a period of working closely together. Ettore had already been married to Fernanda Pivano since 1949, and was mainly an architect at the time. His paintings followed the style of the period, halfway between Picasso and Arp, a form of the Informal, with a hint of the abstract. He also held exhibitions, and it soon became clear that giving shows suited his character and his talent perfectly. Sottsass drew and painted for himself, but the communicative element – when it was given expression in an exhibition – was also very important. He always wanted to communicate, with sketches and with words. He used both languages, especially in his working relationship with Domus and other journals. He also liked to theorize. He was not a born teacher, in the way Achille Castiglioni was (notes from his lectures have just been published in Eugenio Bettinelli’s La voce del maestro, Corraini, 2014) but he liked to pronounce on general ideas, on his activities, on things that needed doing. His vocation, typical of the twentieth century, was to become an artist-theorist.

His writing is at times oneiric and poetic, at others practical, at still others theoretical. His style is reminiscent of Brancusi’s – whom he and Pivano visited – and of Alberto Giacometti’s obsessions published in his collected works. Sottsass’s theoretical analyses are light and airy, almost impalpable, as seductive as a soft cloud. His habitual state of creativity is fizzy, gaseous. As a counterpoint to this volatility in his theoretical framework, he mastered the art of pottery. From talk to action. Pottery was art, in Sottsass’s view: color was more important than form, and form – which was clearly connoted in his work, served only the senses.

In 1958, Sottsass started working at the Electronic division of Olivetti, engaged at the time in constructing a huge electronic calculator known as Elea. Sottsass was given the task of ‘dressing’ the machine, giving it a form that would create an interface with the people working with it. He designed a modular system and transformed it into a piece of furniture. Every cabinet containing a calculator was clothed in aluminum mirror-like panels which gave a diaphanous, steamed over impression. This idea planted the seed for almost all of his future work, though the shapes are still contained in an industrial packaging. In the meantime, Sottsass started experimenting with his esthetic ideas in his painting and pottery, which became a testing ground for the bright colors and playful shapes that would dominate his later work. In these shapes and colors, Giorgio de Chirico’s sense of mystery, together with the painted toys of his brother, Alberto Savinio, are combined. Sottsass continued the tradition, moving into three dimensions, occupying the space of the home, of the shop, of architecture in general. His art was essentially three-dimensional.

Valentine typewriter (1969) for Olivetti

It took him many years longer to achieve a fully mature expression of this combination of playfulness and fun mingled with melancholy and regret: future and past. Sottsass’s creations increasingly acquire an anti-functionalist, playful charm. And yet they are also touched by a sense of the tragic, which is almost invisible but tangible. Like a string that vibrates when it is in proximity of other strings being played. The passing of time is a dominant theme. The fact that Fernanda Pivano was by his side, as many biographers and critics stress, gave Sottsass an entrée to the Beat poets, pop music and India – all of which were formative. In many ways Sottsass was ‘pop’ long before pop hit the scene. He was pop because of his Austrian origin, his love for decoration, for the Baroque, and for anything that belongs to the sphere of popular culture – whether it was a farmhouse of a tram ticket. He was also pop because of he had always been a collector, as he wrote in Scritto di notte, since childhood. His privileged rapport with every day “things” is no different, in his view, from a relationship with “people”, though he often seemed to prefer things to people.

Travelling around the United States with Pivano led to many discoveries that were enacted most successfully in the late 1970s and the early 1980s. This was the legendary side of the story: Sottsass spending time with Alan Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, Bob Dylan and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. A disease, perhaps picked up on his first voyage of discovery in India, nearly struck him down. Roberto Olivetti – an extraordinary character who merits a biography in his own right, given that he founded the Italian publishing house, Adelphi - saved Sottsass’s life in Palo Alto, where his nephritis was finally cured. Convalescing in Room East 128 of the Palo Alto clinic, Sottsass created the first of three journals, ‘Room East 128’ (1962), later to be followed by ‘Pianeta fresco’ (1967-68) and ‘Terrazzo’ in the 1990s.

Journals, in Sottsass’s mind, were art objects themselves, as well as being a transversal message and a privileged act of design on paper. He was a perfect journal maker. Not only was he a proto-hippy, he was also both a designer and a master of internal design, the creator of the Asteroid lamp, of the Olivetti typewriter ,“Valentina”, and of the “Poltronova” armchair. Keeping track of his many activities could be dispersive, but Sottsass’s work challenges this chaos with his total and absolute coherence. The fulcrum of everything is himself, his unequivocal identifying trait that is his own person. He marks himself closely, even when he takes a break, or sets off on a tangent that could take him miles away from everything. Ettore Sottsass’s polar star is Ettore Sottsass. His personality and his activity as a designer and maker of things is marked by irony and melancholy in equal measure. Irony needs a dose of melancholy if it is to avoid becoming sarcasm, if it is to stay light, stay playful. If it is to constantly bounce between making statement and denying it, if it is to make a claim by denying it. Deyan Sudjic, the director of the London Design Museum, confirms this idea when he writes that Sottsass’s approach is the same in all his projects. His houses, Sudjic claims, look like a “free assembly of distinct elements”, like little cities, with buildings grouped around squares. Talking about the architect, Aldo Rossi, Sudjic argues that the feature Rossi and Sottsass share is the “destruction of stable architecture” in order to achieve a “higher level of re-composition” in Deyan Sudjic, Norman Foster: a Life in Architecture, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2010).

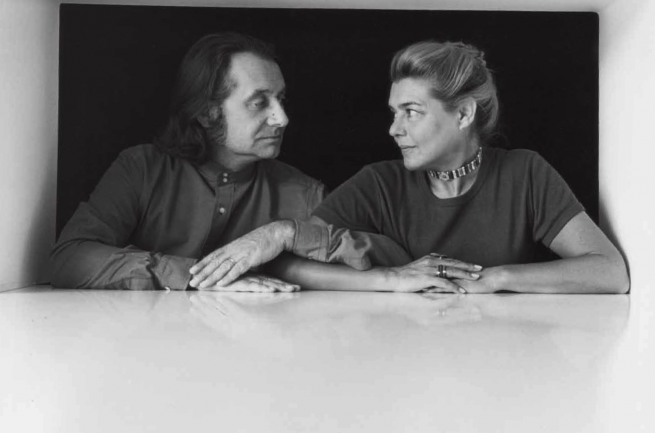

Ettore Sottsass and Fernanda Pivano

This higher level, as Rossi himself said, was the vital erotic charge behind all of Sottsass’s art, including his writing. It is curious that the need for a vital erotic charge, combined with “dissolute melancholy” (Aldo Rossi’s definition) produced in both architects work that was so far from erotic, where color played the most important role. It may perhaps be useful to remember that both Rossi and Sottsass’s building blocks are reminiscent of children’s toys, where stacking blocks is a building game, reusing the same material and creating different aggregates. The shapes are given: a giant Lego or Meccano by means of which the child Eros channels his creative energy and triumphs.

There is so much more to tell about Sottsass’s rich and intense life, from his extensive travels to his founding of Sottsass Associates, from his decision to stop working with Olivetti to his activity as designer of objects and shapes for various commissions, including Alessi. The book contains much of this material. Leafing through it is like dipping into an album, a ring file, a rolodex, the story of his life where his biography and his designs blend into each other and can no longer be separated. The texts are by Emily King and Francesco Zanot, who analyses Sottsass’s photography, which was for the artist a way of seeing, representing, exploring, remembering, recording and enjoying the world around him.

To close this review two quotes from the book may be useful. The first is provided by Francesca Picchi, who cites Sottsass himself, when he claimed his intention was to “place rationalist ideology side by side with a culture of the senses, a culture of weight, smoothness or ruggedness, silence or noise, temperature, asymmetry and dissymmetry, or anything else.” This phrase reminds me of the short stories Calvino planned to write about the five senses ( ‘Under the Jaguar Sun’, Harcourt Brace Jovanovic, 1988) as well as his ‘Six Memos for the Next Millennium’ (Harvard, 1988). There would be an interesting parallel to draw between Calvino and Sottsass for their role in defining the epoch of the 1980s.

The second quotation I would like to give to close this review is from Barbara Radice’s contribution: “Sottsass’s long term aim was not to give form to the world according to the image of design, but to re-formulate design according to the image of the world.” Again Calvino comes to mind, signor Palomar and the failure of the “system of systems”, which were no other than the political and social ideologies during the first half of the twentieth century that Sottsass was so familiar with. In Sottsass’s view of design, the world looks at the world, whatever the established categories of the design world are. Ettore Sottsass had no heirs, Andrea Branzi writes. The only inheritance he leaves behind is himself. A world of objects, images, thoughts, hints, memories. A great deal.

Since 2011

Since 2011