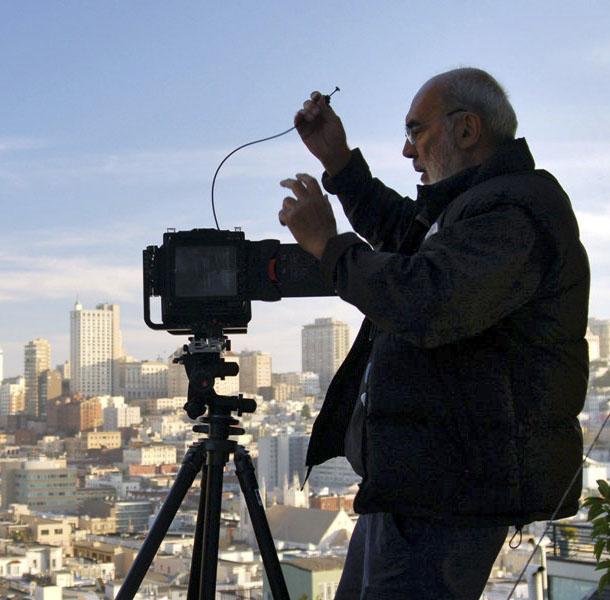

I presented Gabriele Basilico’s last book, Lezioni di fotografia (Rizzoli, 2012), at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan at the end of 2012. Looking tired, but with all his lucidity intact, Basilico spoke about his photography, his choice of themes, his travels, his thirty-year career, and some of his most famous photographs. He also contributed his views on urban landscapes, and on photography as a daily habit and as a life choice.

I have never really believed that the photographic medium has its own specificity. Rather, as I have studied the endless variety of their characters, grammars, functions, vocabularies and themes, I have always seen in photographs as images a deeply uncanny element; in things portrayed are “as they are”, whether they are famous or anonymous, I sense a ghost-like quality, an unexpected hardness, an alien gaze can suddenly transfix me: the darker side of things revealed as a further possibility, a jetty from which to cast off.

In their apparent objectivity, their masterly teasing with metaphysical suspension, Gabriele Basilico’s photographs, in my view, express the turmoil of a sudden recognition – “this is it, it is here, it is this place” – at the same time as the melancholy of a farewell. The places he photographs are depicted as they have never been seen before and will perhaps never be seen again, precisely because the force of Basilico’s images has torn them from their indifferent tranquility – I almost want to say from their invisibility. Basilico’s capacity to grasp shadows, emptiness, nothingness even – a nothingness that leads us to ask all the important questions – is the heritage this great artist of our time leaves us. His photographs, in fact, are so surprising precisely because they are both cosmic and pedagogical, objective and yet theatrical.

The following is my Preface to the book, with a few changes.

Le Touquet, 1985

How can one “read” a photograph? And how does a photographer “read” his or her photos? Gabriele Basilico provides an unexpected answer to these two questions, which would appear to be related and reversible. Reading a photograph, he claims, does not mean making a grammatical analysis of the image. It is not a matter of searching for that elusive formal principle that would identify a point of contact between subjectivity and objectivity, or between interpretation and factual evidence. Nor is it a question of justifying the recurrent traits of the style. Reading a photograph is, on the contrary - as the twelve lectures in this book, Basilico’s testament to his work, show – the practice of intensifying the “impure”, ambivalent nature of the medium. This is both a document and an abstraction, an emotional utterance and an inventory, a story and an eye witness account, a visual sign and a written text. In order to decipher this medium, it is essential to gather together all of its potential cultural ramifications, raise the issue of its use value, and disentangle its more subtle allegorical threads. Hence the necessity for a photographer to remove every image from its dimension as a “message without a code”, and methodically distinguish two levels within each image. First the unique sign, indicating – as semiologists would have it – a place, a landscape, a city. Second, the result of a negotiation with an intention, a project, a commission, a problematic background or an emotional atmosphere. It is the attrition between these two that creates the cognitive and creative value of a photograph, and this has been one of the basic elements of Basilico’s work from the start.

Few photographers have managed to weld their search for more visibility for architecture with landscape art. Visibility, in this sense, meaning the heuristic process that “leads you to see” – with a clear definition of an individual poetic approach - thus creating a dialogue that is on a par with other experiences in contemporary visual arts. Basilico grafted references from the great tradition of documentary report photography, such as Walker Evans’s work, to the typical cataloguing of Ed Ruscha, and to the series of “anonymous sculptures” by Bernd and Hilla Becher. His training as an architect during the critical transition years between modernism and postmodernism served him well. He revolutionized documentary photography by transforming it into a tool for reflecting on urban and natural forms. His militant approach analyzed the complex and never neutral metamorphoses of these forms, while reinforcing the value of self-production. His interpretations of places are both powerful and memorable. They shed light on the story of their survival, of the recurrences and removals that make up the tableau, and form its psycogeographical map.

Dunkerque, 1984

You cannot look at Basilico’s photographs without being affected by a sense of silent immanence. The grandiose changes in scale of the cities, factories, ports, and coastlines in his pictures transfigure the scenes in an almost physiognomic way. The buildings, signs of human labor, ruins of the past and of technology, the generic and the exceptional, are all made up of ‘bodies’, the articulations of which Basilico studies carefully. At the same time, his slow gaze holds them all in a collective embrace. This effect is achieved by means of highly controlled expressive techniques. These include: aligning vertical lines perfectly; studiously but instinctively pointing out the spatial wings or joints that guide the eye towards the depth of the picture; a sense of the horizontal plane being opened wide; the close focus that makes objects seem close up and tangible; the burnished, solemn appearance of the black and white prints; the transparently airy atmosphere of the color images. Basilico’s style is highly personal, one could say he was an immediate classic. And yet, for the same reason, his work was easily surveyed and almost automatically reproducible. In fact, his influence can be felt in much Italian and international urban photography over the last few decades.

The large scale landscape photograph, Le Tréport (1985), is a manifesto of the artist’s desire to forge a startling synthesis between the great tradition of western painting and the very contemporary need to reveal the contradictory nature of the visible world: its historical structure, its palimpsest, the concretion of different imaginations held there, the mystical and cosmic excess that tenaciously inhabit it. In-depth vision and birds-eye views, with their multiple echoes, from Altdorfer to the painters of the Hudson River School, are not so much a topography as a secular and self-aware, yet intimately participated, version of this tension.

Le Tréport, 1985

When Basilico takes pictures, it could be said that he works as an architect. Rather than erecting buildings, he constructs new demands for meaning, new hypotheses for interpretations, which are thrown into both the living space and the natural space. He thus challenges the supposed transparency and objectivity of photography, evidencing its potential to compete with visual experience. At the same time, he highlights the nature of photography as a creative process, which is destined to modify its own starting point just as a work of architecture transforms the collective experience of space. This idea of transformation lies behind Basilico’s decision to compose homogeneous “series” (place and typologies) as well as his choice to present his work as a teaching tool, using contact sheets on which to make annotations, highlight sketches, suggest affinities, recover the latent story of the image, and present them as photograms in a film. Series and “strips” are used by the photographer to gather together and reconfigure visible signs and to reflect a posteriori on their accidental genesis. Once this is done, the photographer can bring their optical subconscious to the surface, and tease out the disturbing elements that inhabit the images as a latent trace, so that they are ready to be activated by our gaze.

Taking a photograph is the equivalent for Basilico of re-learning the hybrid nature of reality. Taking another look at your own images means re-experiencing the same problems as when and how you first set eyes on them. What were the actual conditions that generated the image? How did the image, when it appeared, irreversibly modify the gaze that generated it, by revealing the real and metaphorical shadow of the photographer trapped inside it? It is thanks to this self-conscious virtue that Basilico’s photographs can diverge from their task of documenting reality, without abandoning it altogether. His photographs can transform themselves into an artistic tool that operates on (and by means of) what is visible in order to build new indices of visibility, new aggregations of form and sense, with esthetic and political value. Basilico’s photographs renew the perception and examination of the inter-dependence between uniqueness and context, and between individuals and communities.

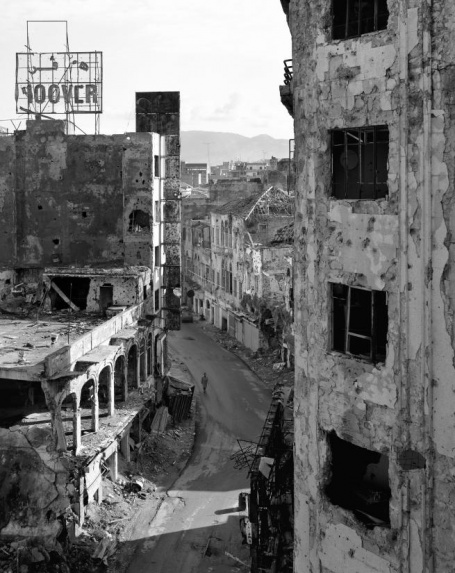

Beirut, 1991

Since 2011

Since 2011