“I’m in Japan here”

Vincent, letter to his sister Willemien, Arles, 14 September 1888

Every exhibition or catalogue on the Japanese artists of The Floating World mentions Vincent van Gogh as one of the figures who, more so than his contemporaries, was inspired by the charm of the first ukiyo-e images that reached the Parisian market in the mid-late Nineteenth Century. But how did Van Gogh imagine ‘his’ Japan?

From his first celebrated paintings after Hiroshige, The Plum Tree and The Bridge in the Rain, from Père Tanguy to the Shoes, from the Parisian self-portraits to the Self-portrait as a Bonze painted in Arles, so many of Van Gogh’s paintings were inspired by the Orient. A look behind the scenes of these pictures draws us into the exhibition Van Gogh: my Japan, at Palazzo Sormani in Milan (until 4 December 2017). Here we are presented with a series of surprising encounters – the literature that inspired the artist, the publishing context of the period, the illustrations, the magnetic covers of Le Japon Illustré, the artworks that Van Gogh himself hung on the walls of his studio in the South. On show are a fascinating array of prints by the Japanese masters of the ukiyo-e genre so loved by Vincent. Among the highlights are the three albums of Hokusai’s renowned One hundred views of Mount Fuji with the great wave (Fuji at sea), Kunisada’s actors and courtesans and Hiroshige’s landscapes.

The exhibition is divided into themes, following the various periods of the life of the Dutch genius. It shows how Van Gogh absorbed the poetry of the Japanese aesthetic and reinterpreted it in a deeply personal style creating a profound synthesis between his inner self and the greatness of Nature.

From Antwerp to Paris

Van Gogh collected “hundreds” of Japanese prints, as we can read in a letter from Arles of the end of March 1888 to his younger sister Willemien. His collection had a joyful start in Antwerp, in November 1885, “My studio’s quite tolerable, mainly because I’ve pinned a set of Japanese prints on the walls that I find very diverting. You know, those little female figures in gardens or on the shore, horsemen, flowers, gnarled thorn branches”. He had just left Holland and its rural palette, and now a new world lay before his eyes: “Well, these docks are one huge Japonaiserie fantastic, singular, strange”, he wrote to his brother Theo.

Vincent was a voracious and multilingual reader. When he joined Theo in Paris in February 1886, he had already read the latest French novels, with their Japonaiseries, especially well described by brothers Jules and Edmond de Goncourt. The novels of the period on show, such as Chérie, Manette Salomon, En 18.. tell of how in the Parisian salons everyone was ‘crazy’ for Japan. Vincent was a great admirer of the Goncourt brothers, as his letters show.

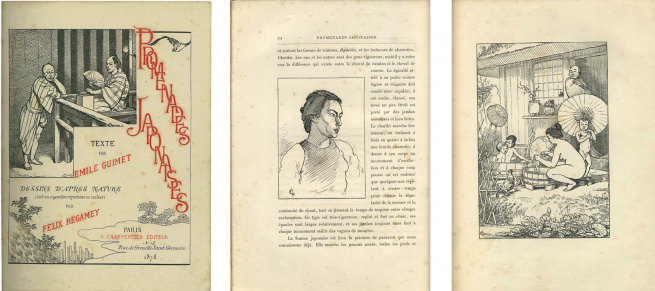

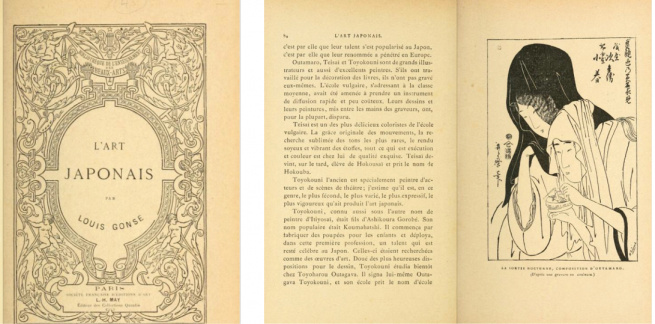

We know little of the two years that the artist spent in Paris. However, on examining the pages of some of the period’s most influential illustrated books on Japan, we discover the visual contamination and the overlaps between western artists of the period and the Oriental approach. Important examples (on show) include Promenades Japonaises (Paris 1878) by Émile Guimet illustrated by Félix Régamey (presented at the Exposition Universelle of 1878) and L’art Japonais by Louis Gonse (Paris, 1883). The publishing world of the epoch exhibited is extremely rich and intriguing: from the magnificent watercolours and drawings from life by Régamey (an ethnographic diary of his long journey around Japan at the side of the collector Guimet), to the curiously imagined drawings of French artists who had never seen Japan, and to the faithful illustrations in Louis Gonse’s volume, in which we see fascinating d’après that bear a double signature (Orient- Occident).

In May of 1886, a special edition of Paris Illustré edited by Sigfried Bing was released. Its renowned cover showed the courtesan by Keisai Eisen reinterpreted by Van Gogh and inside was a lengthy text by Hayashi Tadamasa: for the first time a Japanese native was speaking of his country.

All of this mesmerised Van Gogh, perhaps even more than the Impressionists’ radical theories. From February to March 1887, he exhibited part of his collection of ukiyo-e prints, a real Parisian preview. The show was held at Le Tamburin, a restaurant assiduously frequented by artists, and managed by his friend and model, Agostina Segatori, of whom we have two orientalised portraits. As he had years before with his drawings after Millet, he began his oriental apprenticeship with two famous d’après, after Hiroshige, but he also delighted in experimenting with Japanese calligraphy: he painted ideograms and signatures in the guise of frames for his canvases Flowering Plum Tree and The Bridge in the Rain.

The enigma of the Shoes

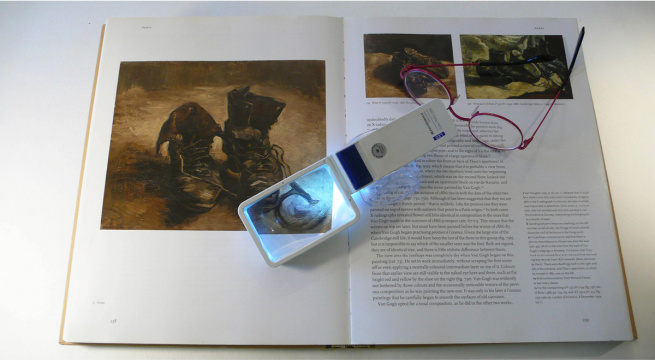

In this visual context, with its porous confines and its desire for experimentation, an “enigma” awaits us, hidden in one of van Gogh’s most famous works. It is a small detail in the right foreground of one of the five versions of the Shoes he painted in Paris. The frontality of the Shoes that so intrigued Martin Heidegger monopolises the attention of the observer, and so this fascinating detail has remained unnoticed for more than a century. Here it is finally brought to light and analysed. Where lies the enigma? Van Gogh transforms the thick lace of the left shoe into something else: a rotund little sprig or root. Oriental writing . . . or so it would seem. This metamorphosis is stunningly impactful. We have a shoelace that is no longer a lace, and that can never again be tied.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Station 40, Chiriu; Utagawa Hiroshige, Station 30, Hamamatsu (ca. 1855)

We are not looking at knotty and twisted branches or roots such as those Vincent had drawn until this point, like in Tree Roots in a Sandy Ground which he produced in The Hague. Instead, something quite different appears, a tiny root that comes to life… like a Japanese tree…? In the joint estate of Vincent and Theo there were many of Hiroshige’s prints – including twenty prints of the Tokaido series of 1855 – in the “tate-e Edition”, the so-called “vertical” Tokaido (the series, part of the collection of the Van Gogh Museum, was completed in 1986 thanks to the gift of 35 prints by the Tokyo Shimbun in Japan). Extraordinary landscapes, where man and nature meld in a perfect balance of strengths. Many of the trees seem to move, contort, even break themselves. Naked roots seem to dance.

Left image, Vincent van Gogh, Shoes (1886), Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum

Beside the Shoes, lit by the light of the lens, we see a rounded root that is tied to a gesture, a gesture of the body and of the mind. It lies there on the canvas that bears it - as if the canvas itself had suddenly been transformed into a piece of writing paper. In the eye of the spectator, it seems like a reassuring, almost poetic gesture. An echo of Japanese calligraphy? There is no stress, no drama in that shape. In a deft brushstroke, the essence of an instant is captured.

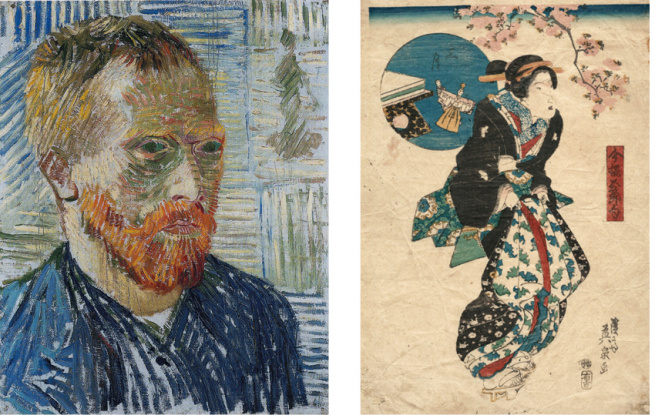

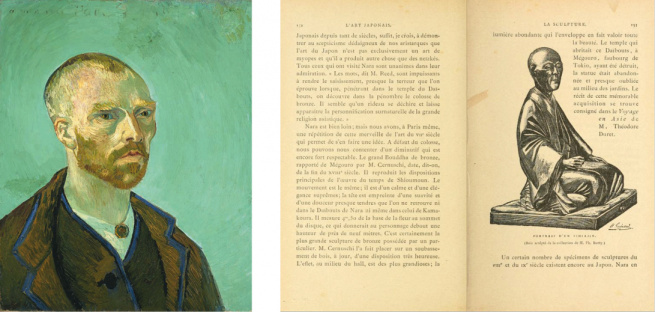

This leads quite naturally to the gaze of the artist as seen in the Self-portrait with a Japanese print, which Van Gogh painted shortly before leaving Paris. Here for the first time his eyes take on an almond shape. Green eyes in fragmented tones, earthly green for the iris and pupil – a sea green for the rest. Provence is calling him and so the dream of the Orient.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait with a Japanese Print (1887), Basel, Kunstmuseum, Dreyfus Stiftung; Keisai Eisen, Woman standing (1820s)

In Provence

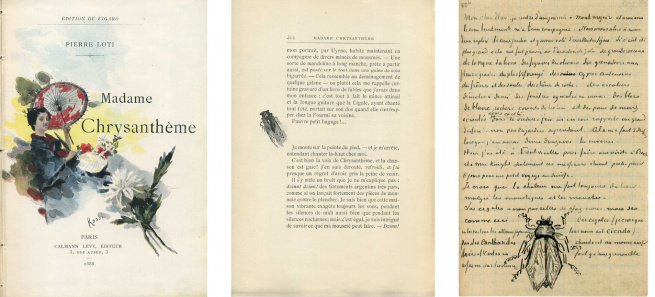

At the end of February 1888, Vincent is in Arles, searching for a livelier sun, a stronger light. “I’m in Japan here”. He plans out small albums of 6 or 10 or 12 views, “like the albums of original Japanese drawings”. In June he reads Madame Chrysanthème, the novel by Pierre Loti set in Nagasaki: “Have you read it?” he writes to his brother, “It really gave me a lot to think about, that the real Japanese have nothing on their walls”. Japanese essentiality. Its beautiful illustrations (by Rossi and Myrbach) enthral him. The girl in the title page was likely the inspiration for his mousmé : “A mousmé is a Japanese girl – Provençale in this case – aged between 12 and 14”.

Loti’s discriptions of nature are very poetic, from “a luminous, calm moon”, to the “warm silence of the mountains”. Illustrated insects are scattered here and there. They must have caught Vincent’s attention: as a young boy he collected aquatic insects, as we read in his sister Elisabeth’s memoires. Crickets, coleopters, cicadas seem to be resting on the pages. The solitary cicada is so beautiful, it appears as though it is almost ready to fly off the page… Loti describes their song in many chapters, according to him this is the “characteristic noise of this country”, a “strident, immense, eternal sound that echoes night and day in the Japanese countriside”.

During that highly creative summer, Van Gogh felt like a cicada: “I even work in the wheatfields at midday, in the full heat of the sun, and there you are, I revel in it like a cicada”, he writes to his painter friend Bernard. Also in Arles cicadas are very noisy, “these cicadas (I think their name is cicada) sing at least as loudly as a frog” he tells Theo in July. Amidst the words he sketches a cicada “not those at home but like this [Vincent’s sketch], you see them in Japanese albums”. He knew the ‘worms and insects’ print by Utagawa Yoshimaro, but Loti’s book really nourished his imagination (as a later sketch of three cicadas from Saint-Rémy also suggests).

Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysantème, title page and one illustrated page (Calman Lévy, Paris 1888); on the right, Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo [638], Arles, 9-10 July 1888, Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum

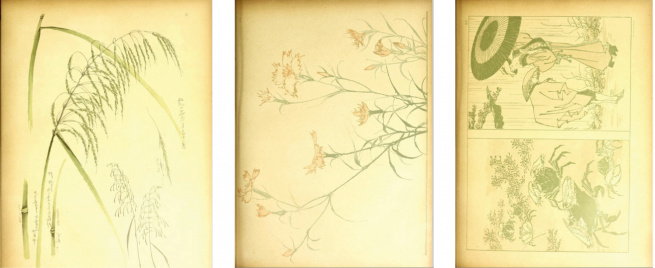

Meanwhile in Paris, in May 1888, Sigfried Bing inaugurates the first Le Japon Artistique. Its cover designs would become iconic: this new monthly magazine was enriched with lengthy articles describing the Japanese way of life, its customs and artisans. It had colour illustrations and many prints and manga that were faithful to the original, with photogravures by Charles Gillot, some of which were included as loose sheets. Vincent soaks up every detail: “Among Bing’s reproductions I find the drawing of the blade of grass, and the carnations, and the Hokusai admirable”, he writes to Theo from Arles.

Anonymous, Study of grasses; Bumpo, Study of pinks; Hokusai, Crabs and seaweed, Persons caught in a shower, in Le Japon Artistique, May and June 1888

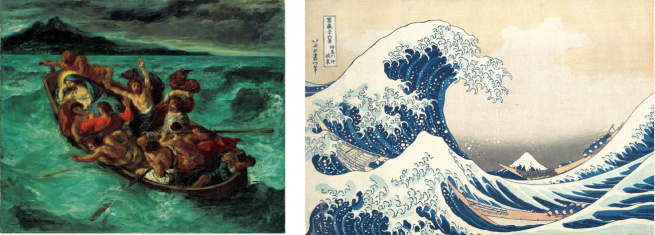

Hokusai holds a place of honour for Van Gogh. He compares him to Delacroix, and to his Christ asleep during a tempest, in a small boat among the waves, that he had seen with Theo on the Champs Élysées. The strength of the colour in that little canvas had struck the critic Paul Manz: “I did not know that one could be so terrifying with blue and green”, he wrote in an article. Van Gogh takes up from here, “Hokusai makes you cry out the same thing – but in his case with his lines, his drawing […] those waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it”, he says in a letter to Theo dated September 8, 1888.

Eugène Delacroix, Christ asleep during the tempest (ca. 1853), New York, Metropolitan Museum; Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa (ca.1830-32)

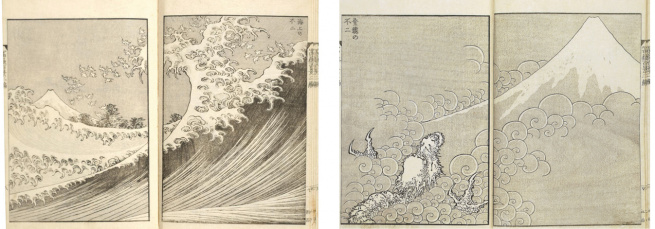

From Provence, he asks his brother to acquire more Hokusai prints from Bing, the “300 views of the sacred mountain and scenes of manners and customs”. Hokusai, following the success of the first series of 36 views in colour, began travelling and created the famous three-volume book of One hundred views of the Mount Fuji, considered his masterpiece. In the second album, we can admire the grayscale version of the great wave, entitled Fuji at Sea, as well as other images of waves and billows that most probably passed through Vincent’s hands. They inspired his thoughts, his backgrounds, his desire to be able to draw at lightning speed. “The Japanese [artist] draws quickly, very quickly, like a flash of lightening, because his nerves are finer, his feelings simpler”.

Katsushika Hokusai, Fuji at Sea; Mount Fuji and ascending dragon (ca. 1843-1835), in: One hundred views of mount Fuji

Thus for Van Gogh, Hokusai was one of the “most skillful of all the artists who sketch from life”, unbeatable for speed and synthesis. Utagawa Kunisada (though never named in Vincent’s letters), must also have been among his favourites for his impactful and evocative portraits. Actors, courtesans, warriors, in his collection there were dozens of them, as well as many other works by artists including Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Toyohara Kunichika and Keisai Eisen. Triptychs of everyday domestic life, of nightlife, of theatre performances, of seasons, flowers, insects, birds and little albums were also well represented. The more than 600 Japanese prints now in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum can be explored online. The collection hails from the joint estate of Vincent and Theo, and was later expanded by Theo’s son, Dr Vincent Willem van Gogh, so it is impossible to reconstruct its genesis.

Utagawa Kunisada, Kabuki Actor (1860), Portraits in mirrors; Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Izutsu Princess (ca. 1842)

Provence, with its uncontaminated nature, its strong sun, was for Van Gogh his “Japan”. “I’d like you to spend some time here”, he wrote to Theo in June 1888, “after a time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye, you feel the colour differently”. The Yellow House in Arles was his Japanese dream, but also a cultural project, a place where painters would live like Japanese artists, immersed in nature, studying “a single blade of grass”. A little corner of the world “with no intrigues” far from Paris, this is what Van Gogh wanted, a community of painters, simple, essential: “it seems, too, that those Japanese earned very little money and lived like simple labourers”, he writes to his friend Bernard.

A labourer of the Arts since 1882, the times of The Hague, Van Gogh knew how to immerse himself in the Dutch woods so deeply that he could make “shorthand notes” and then transcribe onto canvas what nature had “told” him. Thus, more so than other artists, he was naturally inclined to blend with the poetry of the masters of landscape like Hiroshige and Hokusai. For them the natural world with its various elements corresponds to a unique universal force, a unitarian concept of being. Man and nature, nature and man – fundamentally this was the same challenge that Van Gogh struggled with in his constant, ceaseless search: “I always seek the same thing, a portrait, a landscape, a landscape and a portrait […] art is man together with nature”, he wrote from Arles to his sister Willemien.

Today, it is hard for us to imagine the impact those Japanese prints had on the Paris of Van Gogh’s days. It was a time when the Western tradition led the gaze of the spectator towards a vanishing point, gave him a specific position, while Japanese painting instead refused the fixed gaze, allowing the spectator to roam free inside the image. It was a revolution therefore, not just for its flat colours, the structure of the image, the composition, the weights, but also because it was a new window onto the world. Van Gogh welcomed it with open arms and morphed it into his language. He writes Theo with his usual simplicity: “these two drawings of the Crau and the banks of the Rhône which don’t look Japanese and which are perhaps more so than others”. He goes further with his friend Bernard, telling of the hills of Montmajour, where he very often returns to breath in the sensations of that flat landscape below him. “I’ve done two drawings of it – of that flat landscape in which there was nothing but . . . . . . . . . . the infinite . . . eternity”.

He suspends time for his friend as he reads, leaving wide spaces between the dots in the letter; a full line of dots, and in the middle, the infinite. This is the deepest meaning of his personal Japan, and perhaps the most authentic aspect of the Japanese civilisation: at one with the rhythms of the cosmos, and with its spiritual force.

Vincent van Gogh, La Crau seen from Montmajour (1888); The Rhône seen from Montmajour (1888), Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum

The almost aerial views, the tall horizons without a sky, the ink drawings, the waves, the backgrounds or skies sketched with a reed pen at Japanese speed – all in an increasingly personal style – by now these have become a genuine “hand-writing”, personal, confident, unmistakable.

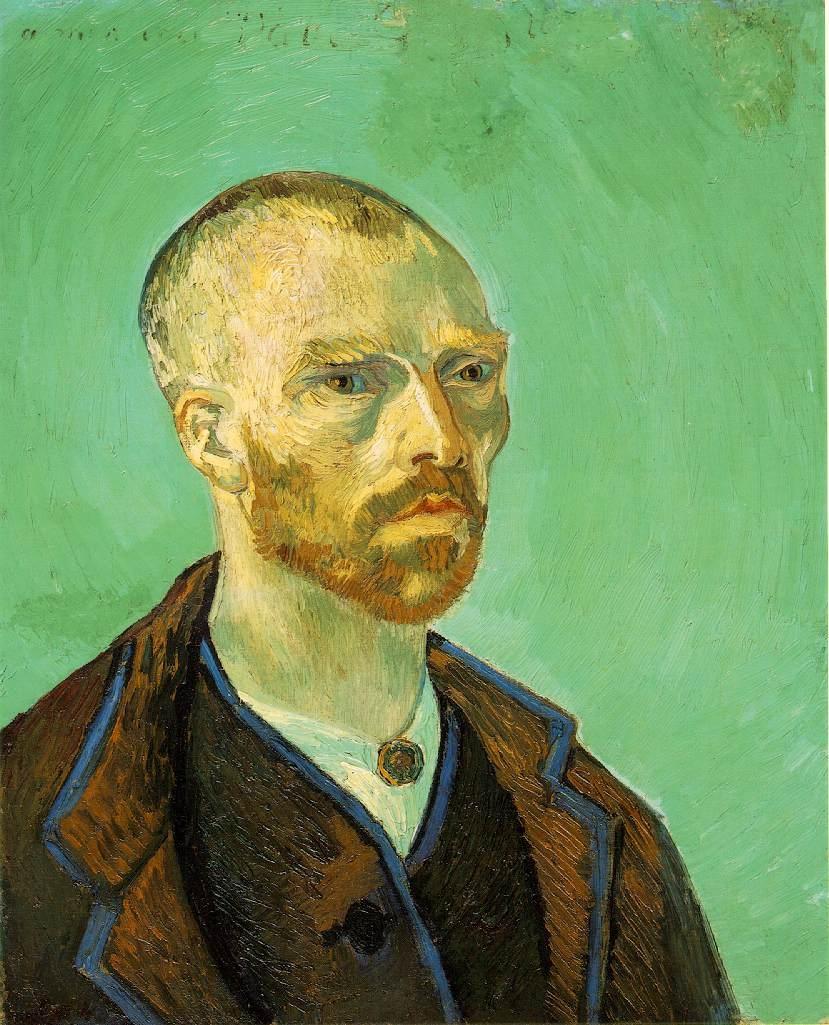

The transformation is also visible on his face – in September 1888 Van Gogh paints the most stunning of all his self-portraits, the artist as a Japanese monk, a “simple worshipper of the eternal Buddha”, his revolutionization of the modern portrait. “The weather’s still fine here, and if it was always like that it would be better than the painters’ paradise, it would be Japan altogether”. September 29 1888.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, Cambridge (MA), Fogg Art Museum; Henri Guérard, Portrait d’un Tshiajin, in L’art Japonais

The English version of Van Gogh’s letters quoted in this article is from: Vincent van Gogh. The Letters (2009), edited by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker (vangoghletters.org). The Van Gogh Museum’s collection of Japanese prints (which includes Vincent and Theo’s collection) can be consulted online. See also Japanese prints. Catalogue of the Van Gogh Museum’s Collection, edited by Keiko van Bremen, Willem van Gulik, Tsukasa Kōdera and Charlotte van Rappard-Boon (Van Gogh Museum, Waanders, 2006); Louis van Tilborgh, Van Gogh and Japan (Van Gogh Museum, 2006); Hokusai, il vecchio pazzo per la pittura, Gian Carlo Calza (Electa, 2010); Ukiyoe. Il mondo fluttuante, Gian Carlo Calza (Electa, 2004). Le scarpe di Van Gogh, Elio Grazioli and Riccardo Panattoni (Riga 34, Marcos y Marcos, 2013) discusses and reconstructs the philosophical debate begun by Martin Heidegger around the painting The Shoes (illustrated above). Also note that the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum is currently holding the exhibition Van Gogh & Japan (24 October 2017 - 8 January 2018) which will then travel to Kyoto (National Museum of Modern Art). The show will open in Amsterdam at the Van Gogh Museum, where it is scheduled from 23 March to 24 June 2018.

(Translated from the Italian by Louise Fitzgibbon)

Van Gogh: my Japan

Milan, Palazzo Sormani, Central Library

The exhibition was on view from 7 November to 4 December 2017

See also on doppiozero: Rocco Ronchi, Van Gogh’s Shoes and Japan

Since 2011

Since 2011