A man in a dark coat turns his back to us. He is painting white letters onto a red banner draped across a table. A Venus de Milo towers before him. The room is grey, an attic, a window, the cable of the electric light, in plain sight, dangling from the ceiling with its lamp. The letters in white proclaim: ВСЯ ВЛАСТЬ СОВЕТАМ, “All power to the Soviets”. There is no palette present, a brush and a glass suffice.

Nikolai Terpsikhorov, First Motto, 1924, Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, Photo © State Tretyakov Gallery

The artist is Nikolai Terpsikhorov, a little known painter who depicts himself carrying out his new duties. By turning his back to us, he draws us into the canvas. First Motto is the work that greets me as I enter Revolution: Russian Art 1917 – 1932, the new exhibition at the Royal Academy of London (until the 17th of April).

Curated by Ann Dumas, John Milner and Natalia Murray, this exhibition takes inspiration from a grand event held in 1932 at the State Russian Museum of what was then Leningrad. “Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic” (“Khudozniki RSFS za 15 let”) was a largescale retrospective, a massive exhibition of post-revolutionary Russian Art, comprising more than 2,600 works by over 400 artists. Curated by prominent critic Nikolai Punin, it was an unprecedented opportunity for artists, critics and indeed the public, but it was also the swansong of the Avant-Garde, coming shortly before Stalin’s violent repression.

“Throughout the anniversary exhibition of 1932, diversity was a persistent feature. The present exhibition aims to refer to that multiplicity by including unfamiliar names of works throughout, not so much to reflect the scope of the 1932 exhibition, but to situate the Russian avant-garde within a wider range of production, some of which has long been celebrated in Russia and neglected in the West” writes John Milner in his introduction to the catalogue.

Boris Mikhailovich Kustodiev, Bolshevik, 1920, Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, Photo © State Tretyakov Gallery

Drawing on that exhibition, Revolution’s trio of curators present us with Avant-Garde artists alongside with those from the many different currents of Socialist Realism that sprouted from the revolutionary spirit. It was a unique period when the revolution seemed to promise freedom and limitless opportunities to transform society and create a new proletarian art. Thus Kandinsky, Chagall, Malevich and Rodchenko to name but a few, are presented side by side with Kustodiev, Filonov, Deineka, Petrov-Vodkin, Brodsky, Grigoriev, Muchina, Samokhvalov and many more (also unknown ceramic or graphic artists), all displayed very closely together for a stunning impact.

We are unused to this intimate elbow-to-elbow cohabitation, without the usual reassuring categorisations by artistic movement. It is this diversity, however, that the curators want to emphasize by focusing on a powerful plurality of viewpoints: from painting to cinema, from photography to sculpture, from architectural studies to posters, advertising, ceramics, commemorative textiles and papier maché objects.

They were all “breathing the same air,” comments John Milner. Revolution acts as the mirror of a truly multifaceted era.

In each section, historical notes tell of failures, deaths and atrocities, reminding us of a reality that cannot be seen in the images before us.

Themes and faces

Alexander Deineka, Textile Workers, 1927, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg/DACS

The exhibition is divided into broad thematic sections spanning those fifteen turbulent years in which anything seemed possible: Salute the Leader; Man and Machine; Brave New World; Fate of the Peasants; Eternal Russia; New City, New Society; Stalin’s Utopia. The sections unravel like a giant fresco, to be examined in minute detail. Over 200 works, mostly on loan from major Russian museums (the Tretyakov Gallery, the State Russian Museum of St Petersburg, the Museum of History of St. Petersburg) as well as from some of the most prominent private collections. Posters, objects, porcelain, textiles, sculptures and documents are displayed alongside a discreet but ever present protagonist: film. Short clips from the pioneering works of Dziga Vertov, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Sergei Eisenstein, Alexander Dovzhenko and others take on a new meaning here surrounded, as they are, by these paintings. Just as in Leningrad, there are two ‘special’ galleries: one is dedicated to Malevich and, for the first time after 85 years, we can experience an exact reconstruction of the original hang decided by the artist for the 1932 exhibition. Three walls are crowded with paintings (and three tables display architectural prototypes - arkhitektoniki), replicating how Malevich, by carefully blending figurative and abstract works, created a highly effective synthesis of his pictorial language.

In the second ‘special’ gallery the curators present the work of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, a fascinating and imaginative artist. Trained as a Russian icons and fresco painter, he studied in Munich under one of Kandinsky’s masters. He also travelled to France and Italy (where he was greatly influenced by Giotto as we can see from his beautiful Petrograd Madonna), and developed his own deeply personal style. He saw the Revolution as a cathartic force, and this can be felt in his works on nature and the circle of life. Theorist of pictorial space, his ‘spherical perspective’ characterises his oeuvre as intensely spiritual. Ann Dumas hopes that the room dedicated to him will be “a discovery for many and help to make this artist’s work known”.

Throughout Revolution, you meet faces you won’t forget. Each section pulls you along with magnetic gazes, some smiling, some seemingly frozen, some heroic, others robotic or dream-like. The barefoot workers of Alexander Deineka move among huge bobbins that, stored high on the right of the canvas, become a purely graphic device. At the same time, the robot-worker holding an almost invisible thread in her hands leaves me breathless. A life-size figure, she appears frozen, staring fixedly into the void (Textile workers, 161 x 185 cm). Next to her, I encounter the sunlit statuesque shoulders of a worker-hero on his iron machine “pedestal”, in Isaak Brodsky’s famous canvas celebrating the building of the dam on the Dnepr (Shock-worker from Dneprostoi, 1932). In the next gallery Boris Kustodiev transforms the view from his window into a fairy tale scene. A Bolshevik-giant strides through a crowd of miniscule figures that flood the streets (Bolshevik, 1920). The giant’s eyes look glassy; he seems to march blindly along, guided by some mysterious voice.

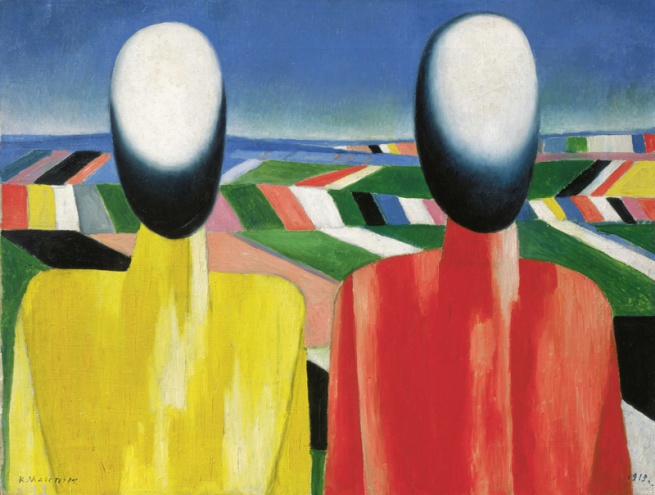

Shortly afterwards comes Malevich’s canvas - a void of total facelessness.

Kazimir Malevich, Peasants, c. 1933, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg/DACS

A few steps further on, a string of staring peasants makes me brake suddenly: the faces in the centre and the two seeming twin boys to the left, are only slightly larger than life-size, but their impact is stunning (the canvas measures 90 x 215 cm). Boris Grigoriev travelled extensively through the Russian landscape exploring the core of these peasant faces with the passion of a sculptor (he had studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris from 1912 to 1914). To them he dedicated a series of paintings entitled “Rasseya” (Russia), which he worked on from 1916 to 1917, creating very striking compositions. Religious and superstitious, the peasant class represented a problem for the Bolsheviks. In Land of Peasants (1917) the eyes already betray their tragic fate. Almost fifteen years later, during the forced collectivisation of the agricultural land, Pavel Filonov paints the two stone-like eyes of a Collective Farm Worker (1931). His gaze is resigned to a destiny that seems to weigh on his shoulders instead of the open fields. It’s nothing like the revolutionary abstraction that he painted years before: in his Formula of the Petrograd Proletariat collectivism was translated into a fluid burgeoning of small beautiful elements. Stalin had celebrated his fiftieth birthday two years earlier, in 1929, beginning the process of his sanctification as benevolent Father and friend to all children. All of the power was in his hands. The struggle against the kulaks escalated into mass executions. The systematic closure of churches began.

Boris Grigoriev, Land of Peasants, 1917, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2017, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

I return to the first hall of the exhibition, Salute the Leader, to pause again Beside Lenin’s Coffin. This is a portrait by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, one of the very few artists allowed to sketch at Lenin’s funeral. Hidden for decades from the public eye (now in the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery), Russian-born co-curator Natalia Murray decided to bring it to London. “We have other and better portraits of Lenin, so why don’t you borrow them? And, “Why do you want a portrait of a dead Lenin lying in state?”… these and similar questions were raised by the curators of the Moscow gallery, who were quite surprised by her request for it, Murray said in an interview. The tradition of the times dictated that portraits should depict Lenin alive, but here the artist’s hand accurately captured him in his coffin, and sketched “from life” what he would later work up in his studio, painting the subject in a holy light. We are transported to Moscow, inside the Pillar Hall of the House of the Unions, it is the 23rd of January, during the bitterly cold Winter of 1924 (Lenin died on the evening of the 21st). The idea of exhibiting Lenin in his coffin clashed vividly with the institutional message: Lenin is alive. Still today, this portrait is rarely displayed to the general public.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Beside Lenin’s Coffin, 1924, Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, Photo © State Tretyakov Gallery

But what made that 1932 exhibition in Leningrad so “special”, so inspiring to our trio of curators? My curiosity drove me to the British Library to delve further into the dynamics of the 1932 and 1933 (Moscow) exhibitions, as well as to explore the pages of the book that Natalia Murray dedicated to Nikolai Punin and his times.

Leningrad, 1932

On the 13th of November, the grand exhibition of Leningrad opened. The show commemorated the first fifteen years of Russian art, counting 1917 as its symbolic start date. It involved some 2,640 works (1,050 paintings, 1,500 graphic works and 90 sculptures) by 423 artists from all of the artistic tendencies that, as John Milner reminds us, “were competing for the attention of that single collective sponsor, the State”.

Masha Chlenova, in her contribution to the exhibition’s catalogue (“Soviet art in review: ‘Fifteen years of artists of the Russian Soviet Republic’ in Leningrad, 1932”, 2017, pp. 27-31), reconstructs the background to the grand event. Her research includes materials and manuscripts from the Manuscript Division of the State Tretyakov Gallery. The idea for the retrospective was conceived in January (1932), and initially the chosen location was Moscow which, however, lacked a suitable exhibition space. Leningrad instead offered the immense halls of its State Russian Museum. The bureaucracy of the period demanded: a Government Committee, led by the newly appointed Commissar of Enlightenment Andrei Bubnov (a Stalin supporter, who in 1929 succeeded the liberal Anatoly Lunacharsky, nominated by Lenin in 1917), for its general ideological direction and budget; an Exhibition Committee with artists, museum curators and scholars to select the works; and an on-site working group comprising the State Russian Museum’s deputy Director and two curators of twentieth-century art, Nikolai Punin, and Nadezhda Dobychina, both of whom had supported the Russian avant-garde.

Nikolai Punin, an influential art critic, writer and theorist closely tied to the avant-garde, was from 1926 onwards chief curator (and founder) of the Department of Newest Trends at the State Russian Museum. Nadezhda Dobychina owned an Art Bureau (1911-1919) in what was then Petrograd, and in 1915 she held the famous and well-documented exhibition ‘The last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0–10”, which was to become a milestone in history of art. Many possible exhibition titles were discussed, from Soviet Art over Fifteen Years, to Fifteen Years of Soviet Power, finally deciding upon Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic (Khudozniki RSFS za 15 let), highlighting the role of the artist; Artists of RSFS – in 15 years, it could be said.

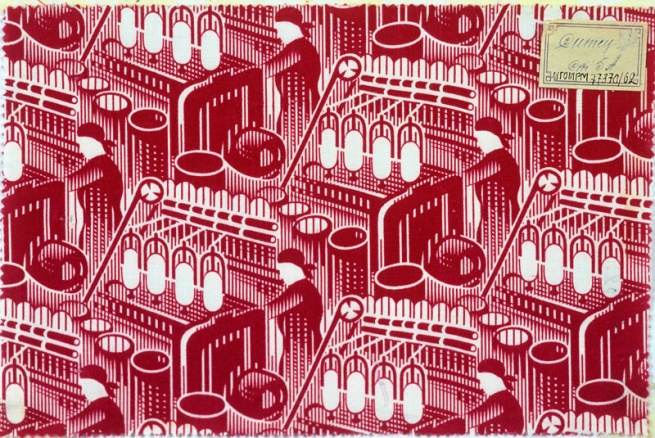

Andrei Gobulev, Red Spinner, 1930, Cotton Print, direct printing cinz, The Burilin Ivanovo Museum of Local History. Photo © Provided with assistance from the State Museum and Exhibition Center ROSIZO

This evolution is fascinating given that, in his introduction to the catalogue of the 1932 exhibition, Mikhail Arkadiev (the vice-chair of the Exhibition Committee and the Head of the Art Section of the People’s Commissariat of the Enlightenment) underlined that the main political function of the retrospective was to show how individual Soviet artists “gradually mastered the Socialist outlook of the proletariat” and “ joined the socialist construction”.

The painter Igor Grabar, another key member of the committee, described the show as “an examination for the certificate of artistic and individual maturity of single masters and of entire artistic groups” (Chlenova, ibid., p. 28).

Without doubt: the organisers had to adhere to the decree of the Central Committee of the 23rd April 1932 (while the retrospective was still in a preparatory phase), banning all of the existing artistic movements. In short, they had to show that the various artists would now work “pacifically as a united front”, with no further disagreements and no competitiveness amongst the single groups.

Petrov-Vodkin’s rider, with his uncertain backwards gaze, seems to foretell the doom of the revolutionary ideals. His mount is no longer that of the iconic work Bathing of a Red Horse, now it gallops above a shaken world (1925). A year after Lenin’s death, dreams had already begun dissolving into thin air.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Fantasy, 1925, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg/DACS

Red carpets, draperies and the hammer and sickle at the head of the grand stairway entering the State Russian Museum, with green plants and floral compositions – everything was the height of fashion at the opening event on the 13th of November. The solution: the route through the exhibition was circular, “which established a symbolic continuity between its starting and ending points” (Chlenova, ibid., p. 29).

The circular lay out was not arranged chronologically, instead it aimed to highlight the evolution of each individual artist over a fifteen year period, offering crucially important examples of how “they could adapt their work to the changing needs of the Soviet society” (ibid., p. 28).

The lion’ share of the vast space available was dedicated to artists from the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (AKhRR) who, with their central protagonist Isaac Brodsky, strongly opposed the Avant-Garde. Their works were displayed in a dialogue with the artists of the OMKh (Society of Moscow Artists), the Society of Easel Painters (OST), amongst whom David Shterenberg and Alexander Deineka figured, as well as with the Wanderers, to name but a few.

Nikolai Punin diplomatically described how the various groups interacted with each other: “The Artists of Revolutionary Russia learned to lighten up their paintings by looking at the legacy of Paul Cézanne and other Western modernists in the works of the Society of Moscow Artists, while the latter were inspired by the realist tendencies of the late nineteenth-century Russian painters known as the Wanderers” (ibid., pp. 29-30).

In an article published just before the inauguration, Punin announced that “The main principle of the display is to showcase in the best possible way the individual identity of an artist”. Seven key figures received their own room where they could hang and position their works freely.

Amongst these, the brave Punin managed to include only two representatives of the “left”: a room was assigned to the father of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich, and another room went to Pavel Filonov, the inventor of the so-called “Analytical Realism” and founder of the Collective of Masters of Analytical Art in Leningrad.

Pavel Filonov, Formula of the Petrograd Proletariat, 1920-1921, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2017, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The second gallery, however, would be bluntly cut out of the program. It “was originally supposed to showcase the period of War Communism, dominated by leftist art”. Instead, the committee decided to remove it “for reasons of space” (Chlenova, ibid., p.29). Bottom line: any other abstract or Constructivist works stayed in storage.

Moscow, 1933

The overseers decided to “repeat” the exhibition in Moscow and, on the 27th of June, it reopened on Red Square at the State Historical Museum.

The title was unchanged “Fifteen Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic” (Khudozniki RSFS za 15 let), but it was now also presented as a “Review of Soviet Art”. The artists included were nearly 500 with almost 3,500 works, distributed across several sites. The panorama of Russian art in those same fifteen years had undergone a substantial shift. In fact “only half of the paintings by the avant-garde artists which had been exhibited in Leningrad were actually shown in Moscow”, writes Natalia Murray in her book. “Miturich, Suetin and Tyrsa were mysteriously excluded from the Moscow exhibition, and only five out of the 73 paintings by Filonov exhibited in Leningrad came to Moscow”. Malevich could hang just a few paintings but his work was not included in the exhibition catalogue. Unlike Punin, the Moscow curators had no intention of risking their jobs “for the sake of an exhibition of alternative art – Socialist Realism was already knocking at the door” (Natalia Murray, The Unsung Hero of the Russian Avant-Garde. The Life and Times of Nikolay Punin, Brill 2012, p. 200).

In his inauguration speech, Andrei Bubnov said that the Moscow show “witnesses the turn of the majority of our artists to the positions of working class”. In the new catalogue, there was also an article by Mikhail Arkhadiev who proclaimed: “The Style of our era – is Socialist Realism”. He also criticised the Leningrad exhibition for its failure “to show the whole dynamics of the development of Soviet art” and “the right forms of visual art, which are necessary for the proletariat in its fight for victory of Socialism” (ibid.).

In just a few months, all of the catalogues of the Leningrad show (closed in January 1933) were removed from the shelves of every library and bookstore. “Even today, only the catalogue of the Moscow exhibition ‘Artist of the RSFSR – the first 15 years’ is available in Russian libraries”. Same title, different contents. A radical form of memory tampering. In a note, Natalia Murray adds that “In public collections, the only copy of the catalogue of the Leningrad exhibition can be found in the library of the Russian Museum, which is closed to the general public” (ibid., p. 201, note 26).

This explains why the show that inspired Revolution was never documented. It slipped through the cracks, barely mentioned anywhere in art history texts. On the contrary, it marked a turning point, a vital chapter in the history of Russian Art at a crucial time of transition. It was also a highly convenient opportunity to expedite the marginalisation and even elimination of those artists who did not correspond to the new political ideals. Shortly to be locked away in the basement of the Russian Museum, “paintings by Malevich, Filonov, Tatlin and other Avant-Garde artists were now seen as bad anti-Soviet art, which had to be avoided” (ibid., p. 201).

With Stalin’s cultural-political revision steamrolling ahead, the active artistic groups were abolished and soon transformed into the Union of Artists, the Union of Musicians, and so on. From that time onwards, art’s only function was to “re-educate” the masses. The State, interested in just one type of artistic product had to reorganise its investments to make this massive machine manufacture millions of copies of the required institutional imagery.

Ideology and mythology made into reality.

And what of Nikolai Punin, the forgotten hero rediscovered by Natalia Murray, who fought right from the start for innovation in art, openly criticising Socialist Realism?

As he adventured into ever more dangerous territory he was gradually marginalised, and his articles and books were no longer published. In mid 1930s he was hardly keeping a diary and was arrested on several occasions. In 1949, he was condemned for having criticised socialist realist paintings by Vladimir Serov as “insipid and characterless”, and sent to the camp near Vorkuta where he died in 1953.

From the left: Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Portrait of the Poet Anna Akhmatova, 1922, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2017, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; Kazimir Malevich, Portrait of the Art Critic and Curator Nikolai Punin, 1933, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Photo © 2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

He had been the companion of Anna Akhmatova, they had lived together for many years in the rooms of what is now the Akhmatova Museum in St Petersburg. It was Punin’s apartment where intellectuals met to speak freely, in the years when such a thing was still possible. Reunited in this exhibition, their portraits: on one side we see the face of Akhmatova painted by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, on the other, the profile of Punin by Malevich. Alongside them, beautiful photographic portraits draw us to the magnetic faces of Mayakovsky, Blok, Shostakovich and Meyerhold photographed by Moisey Nappelbaum and Alexander Rodchenko.

Utopia and memory

Sport, running and physical discipline are the stars of this final theme of the exhibition: Stalin’s utopia. Strong men and women – attractive and vigorous – welcome us as perfect examples of the new heroes. Here too the artists are called upon to promote Stalin’s ideology. Alexander Deineka is among the most audacious, his athletes move or better float through space weightlessly. Then it is the turn of Alexander Samokhvalov’s muscular and anonymous girls, depicted in sportswear and football jerseys (1932-1933). Nevertheless, it is a shot by the extraordinary photographer Arkady Shaiket who, with his bird’s eye view of the morning collective marches, reminds us what these vitally important public displays really were - a grandiose investment in image: Physical Training. Morning Gymnastics (1927).

At the centre of this section lies a large black cube - the Room of Memory. Entering it, I pass by a quote from Anna Akhmatova: “No generation had a fate like that in history”. Inside are two benches, the room is dark. A slideshow displays dozens and dozens of photographs from the archives. One after another, front and side prisoner mugshots, each with a number; below the footnotes tell us something of their identities and destinies. Chemists, engineers, economists, politicians, scholars, writers, composers, artists, thousands of ordinary citizens, men and women. It is now impossible to recognise some of the faces I have just gotten to know in the exhibition, like Vsvelovod Meyerhold or Nikolai Punin. We leave bidding farewell to the dead.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932

Royal Academy of Arts

London, 11 February – 17 April 2017

Nicolai Terpsikorov, First Motto, detail, 1924, Moscow, State Tretyakov Gallery, Photo © State Tretyakov Gallery

Catalogue: Revolution. Russian art 1917 – 1932, with contributions from John Milner, Natalia Murray, Faina Balakhovskaya, John E. Bowlt, Masha Chlenova, Ian Christie, Christina Lodder, Nicoletta Misler, Nicholas Murray, Mike O'Mahony, Evgenia Petrova, Zelfira Tregulova and Lauren Warner.

Since 2011

Since 2011