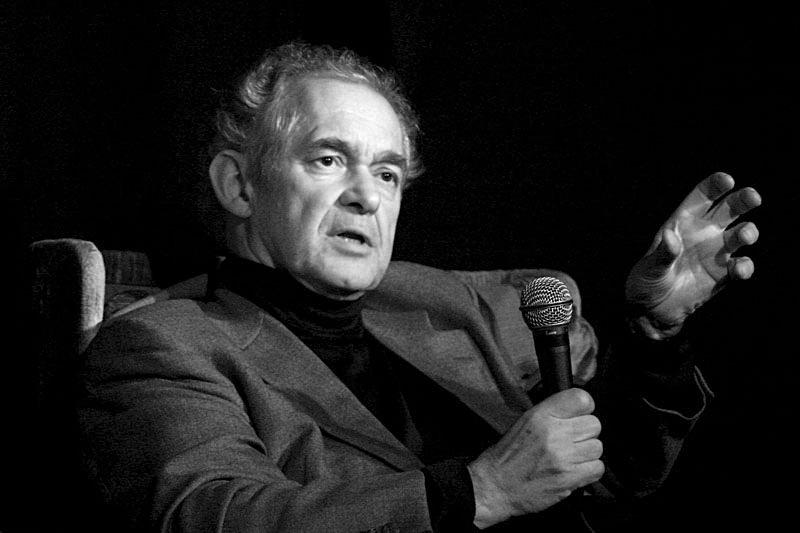

Christoph Wulf teaches Anthropology and Pedagogy at Freie University Berlin, where he is a member of the Interdisciplinary Center for Historic Anthropology, of the collaborative research center (SFB) on Performativity, of the center of excellence ‘Languages and Emotions’ and of the Graduate School ‘InterArt Studies’. Wulf studied History, Pedagogy, Philosophy and Literature at Freie University and received his PhD at Marburg in 1973 where he also passed his habilitation in 1975. In the same year he was given a chair in Pedagogy at University of Siegen. As professor he returned to Freie University Berlin in 1980.

Wulf was a founder member and is one of the main exponents of the Berlin school of historical-cultural anthropology, which combined methods and research topics from different academic disciplines in a transdisciplinary and trans-cultural perspective; he is one of the world’s best known scholars in pedagogy and anthropology. His work in anthropology and pedagogical anthropology is considered as a milestone in the field. In particular, his studies on mimesis, performativity and rituals are important reference points for researchers.

Because of the importance of his research, Wulf has been invited to serve in many German and international research commissions; He has been visiting professor at the universities of Stanford, Tokyo, Kyoto, Beijing, New Delhi, Paris, Lille, Strasbourg, Modena, Rome, Amsterdam. Stockholm, Copenhagen, London, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. Since 2008 he is Vice President of the German Commission for UNESCO (see Christoph Wulf Der Mensch in der globalisierten Welt. Anthropologische Reflexionen zum Verständnis unserer Zeit. Christoph Wulf im Gespräch mit Gabriele Weigand. Muenster: Waxmann: 2011).

In this interview, Wulf reviews his historical-cultural anthropology and demonstrates the unique approach of the Berlin school of historical cultural anthropology and develops some of the main categories and dimensions that form his anthropological theory and method.

***

Berlin is very well known as the research place where – at Humboldt University, starting with F. Kittler’s work, as well as at the Freie University thanks to your own research – important new “schools” of researchers and academics started working on innovative subject matters, with the common interest in interdisciplinarity. This research gave rise to the so-called “Kulturwissenschaften” (Humboldt University), on one hand, and to cultural-historical anthropology (Freie Universität), on the other; both schools have achieved significant results in terms of scientific achievements, publications, workshops, and research exchanges and continue to prove vital and attractive to young researchers. In our series of “doppiozero” interviews, we have already met Prof. Thomas Macho from Humboldt University, who told us about his research in the field of “Kulturwissenschaften” and their the methodological and theoretical problems. Now we would like to discuss with you the research school based at the Freie University and to learn something more about your effort to promote a new understanding of anthropology, by theorizing a “cultural-historical anthropology”, which seems to combine two different approaches. What did the combination of these two adjectives – historical and cultural – to characterize anthropology mean for you, when you first started developing this discipline, and what does it mean for you today?

Our anthropological research started ten years before Kulturwissenschaften was founded at Humboldt University; we have always maintained close research affiliations with their school. From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, Ditmar Kamper and I set up a far-reaching trans-disciplinary and trans-cultural research project called Logic and Passion (Logik und Leidenschaft). More than 150 colleagues from more than 25 academic disciplines and ten different countries took part in this project, which was the first of its kind at the time. Collaboration with our Italian and French colleagues was an essential component. The first volume of our ten-tome series, The Return of the Body (Die Wiederkebr des Körpers) marked a milestone in the development of the corporeal paradigm in the humanities. Collective studies on the anthropology of the senses, on time, beauty, holy, love, the soul, laughing and silence followed. The conferences that took place in Germany, France and Italy were the early seeds of what became the Berlin school of historical anthropology. We were interested in developing an anthropological perspective within different academic disciplines and to promote transdisciplinary and transcultural research on the basis of different disciplines. That is why, in the early 1990s supported by several colleagues I suggested the foundation of a commission inside the German Society for Educational Science (DGfE) devoted to Pedagogical Anthropology (Paedagogische Anthropologie), which by now has produced more than 25 volumes on Pedagogical Anthropology based on the results discussed in annual conferences.

In the first ten years we focused on research into the historical anthropology of Europe, which produced knowledge that also was essential for the pedagogical anthropology commission. We published a selection of our main research results in a volume with the title Logic and Passion (Logik und Leidenschaft, Berlin 2002). When we talk about historical-cultural anthropology what we mean is a conceptual widening of the field, that I have developed both in a diachronic and synchronic dimension. This widening started by conducting in-depth research in the context of the Berlin studies on Rituals and Gestures (Berliner Ritual und Gestenstudien) which studied rituals in four different areas of socialization – family, school, peer groups and the media – and which led to a rediscovery and new appreciation of rituals (see Ritual and Identity, London, 2010). The research produced 20 doctoral theses and became the bedrock of ethnography of education that gained increasing importance in the years that followed. Given its long-term nature, the research that widened this specialized field from within also achieved international renown. Further research on the meaning of birth, family happiness and emotions was to follow. The common feature of this vast range of research was its ethnographic approach. Thus, it was the historical and cultural anthropology (or ethnography) approach that formed the historical-cultural character of the Berlin school of anthropology.

How would you specifically describe the role of philosophical anthropology, namely of that German tradition that is mostly linked to the names of Max Scheler, Helmuth Plessner and Arnold Gehlen, according to your conception of anthropology? Thanks to the new lines of research opened by ethnological studies, which have brought an end to the primacy of the White, Western (i.e., European) male as the focus of anthropological investigation, it seems that philosophical anthropology has gained a renewed significance, helping researchers face the methodological problems derived from comparativism. However, this discipline first had to give up all essentialist conceptions of the human being. What role does philosophical reflection play in your understanding of anthropology?

While philosophical anthropology, developed by the authors you mention, aimed at understanding people in general, the aim I pursue by means of historical-cultural anthropology is to focus on particulars, and discover their historical and cultural uniqueness. This does not mean that the question of what we all have in common does not have resonance for me. Anthropological philosophers have tried to identify what distinguishes people from animals. They were interested above all in the differences between human beings and animals. Today people want to know what humans have in common with non-human primates and with animals. Unlike anthropological philosophers, my research has underlined the significance of culture in the genesis of humankind. I am interested in people’s historical and cultural variety, in alterity and its significance for living together within a globalized world.

Anthropological philosophers have attempted to contain humankind in a single conception, and I have seen the evident limits of this approach. It necessarily leads to abstractions and generalizations that create problems in their turn. By contrast, I am drawn by the conviction that humankind cannot be explained by one or two principles. Its complexity can only be understood in terms of a mutual co-penetration of varying dynamics. What historical-cultural anthropology enquires into is precisely these dynamics. Research takes place in the full awareness that there is a double historicity and culturality. Historical-cultural anthropology has grown from, on the one hand, through the historicity and culturality of the researcher, and on the other, through the historicity and culturality of the phenomena under observation, as well as their social interconnections. I claim that the double historicity and culturality of the subject and the object plays a vital role in today’s globalized world (see, for example, ‘Anthropology. A Continental Perspective’, Chicago, 2013). A pluralism of perspectives cannot be changed at whim. Rather than disclaiming supporters of anthropological philosophy, I’m insisting on the complexity of anthropology, which makes it impossible to gain complete knowledge of humankind (see Mensch und Kultur, 2010). In my view, self-reflection and a critical conscience of the possibilities and the limits of anthropological research are fundamental cornerstones of the discipline of anthropology.

A core theme of both Kulturwissenschaften and anthropology is the concept (and the event) of death, its symbolization, interpretation as well as representation. Both Thomas Macho and Byung-Chul Han, whom we have already interviewed, started their academic careers by writing on this topic, which you have also investigated over the past years. It seems to me that, since the concerns about something like a “human essence” are no longer at the core of anthropology and the answers coming from religion are no longer satisfying – when the issue is scientifically addressed – the intricate problem of the meaning of life has now turned into the (possibly more intricate) problem of the meaning of death. The history of such a theme is of course a long one, but what I find most interesting is the fact that we are currently witnessing, at least in philosophy (starting from Foucault’s biopolitical paradigm), a new understanding of life, which is inextricably connected to the notion (and practices) of death, since the way in which bio-power essentially governs human lives is by governing (the techniques of) death. How would you interpret this problem from your point of view?

As long as the inconsistency and the caducity of humankind is insuperable, research on death will always be a central pillar of anthropology. As the process of hominization shows, human mortality is a basic condition for the development of homo sapiens sapiens. However painful it is on an individual level, the development of humanity has only been made possible by the death of single individuals. The awareness of the caducity of our bodies is a constitutive element of our temporal and spatial conscience. The awareness of our mortality and historical and cultural enquires linked to this awareness of death are both essential research questions in anthropology. Death and dying, however, are not challenges only for the individual. They are also an element of collective cultural and historical life, in variously structured ways. It is a fact that social power is ultimately based on holding power over human life. The intensity of debate today over euthanasia, organ donations and our relationship with death are an eloquent illustration.

In any case, in addition to being interested in death I am also fascinated by birth. For this reason I led a research project funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinshaft), which looked into the transition from being a couple to being a family after the birth of a child (see Geburt in Familie, Klinik und Medien, 2008, or Das Imaginäre der Geburt, Munich 2008). Part of this project focused on representations of birth developed by hospital administrators and in birth clinics. Furthermore, we were interested in the practices linked to birth within these institutions. Finally, we analyzed the conceptualizations of birth offered by numerous television programs on the theme. The overall picture of the social and cultural significance of birth was highly variegated. As a corollary, we also researched the theme of the birth of our society – and in this area references to biopolitics were essential. I would be interested in working on a historical-ethnographic study of the relationship between birth and death where the multiplicity of representations elaborated by mankind are taken into account.

With Thomas Macho we discussed the problem of the method to be followed by researchers in fields such as anthropology, ethnology and cultural studies which are characterized by multiculturalism and cross-disciplinarity. In these fields it is difficult to point to fixed criteria we can rely on without doubt, in order to avoid the weaknesses caused by a methodology that is too vague. You work on a variety of themes and a range of different fields as well, so I guess the method you follow in each case mostly depends on the specific problem you are addressing and on the aims of your research. However, are there any principles or procedures that you would describe as being constant in your work and essential to your own method?

Unlike the epistemological conception of critical rationalism, which considers the character of science as guaranteed inasmuch as it follows a normatively and scientifically determined method (that is the quantitative research method), studies in the humanities usually try to develop their methodology in relation to the research question that has been posed and to the state of art of the situation. In my research methods, procedures and orientations from the study of history, literature, ethnology and philosophy all play a vital role. Normative questions also play an important role in the methods proper to social science and spiritual enquiry. In ethnographic research, for example, these questions are already apparent in the way we perceive phenomena. This aspect became particularly evident when I was working on a project with three teams of researchers, each with one German and one Japanese researcher. In this trans-cultural project, it was not only the interpretations of phenomena that presented differences; perceptions and descriptions of phenomena revealed cultural differences from the start. Managing a trans-cultural project of this kind is a challenge in itself and the search for solutions by means of innovative research methods is essential in a globalized world. In addition to the cultural background of the various interpretations and perceptions, the differences of perception and interpretation of the supporters of the various academic disciplines are also revealed. I have experimented with this in particular in the collaborative research center on Performative Culture (Kulturen des Performativen). Historical-cultural anthropology is less an academic discipline then an approach to study phenomena, themes, issues, and ways of dealing with them; research in historical cultural anthropology is a dynamic process that can be developed interculturally in the framework of one or more academic disciplines (see ‘Anthropology. A Continental Perspective’, Chicago, 2013).

In 1996 you edited a book on the theme “anthropology and violence” (Das zivilisierte Tier. Zur historischen Anthropologie der Gewalt, ed. by M. Wimmer, C. Wulf, B. Dieckmann, Fischer Verlag 1996). Violence has always been a huge topic in philosophy and cultural studies and in contemporary debate (at least from Michel Foucault’s analysis onward) its relationship with power and life has become a central topic of biopolitics. Could you sketch out the significance of such a topic from the point of view of historical and cultural anthropology, as well as from the point of view of pedagogic anthropology?

Already in the early 1970s I had started researching the issues of peace and conflict. In 1972 I founded the Education Commission within the International Peace Research Association, which is still active today. By means of its mission statement I contributed, to a certain extent, to developing the idea of Critical Education for Peace (see Kritische Friedenserziehung, 1973), which was based on the conviction that the problems linked to peace are not only a matter of individual behavior or attitude, but are strictly linked to social and international structures and their potential for violence. In addition to manifest violence, it is important to consider structural and symbolic violence, which is essential to analyze in the context of political education or in connection with Global Citizenship Education. When we talk about globalization, poverty, oppression, exploitation and violence must also be taken into account as manifestations of globalization.

My ideas are based on the belief that the future of humanity will be determined by how it responds to three challenges. The first consists in the violence endemic in the world, its international system and its social structures. The problem is not only constituted by manifest forms of violence such as war, terrorist attacks et alia (although there are still 18,000 atomic and hydrogen bombs that could be used to blow the world up at any time), but also by a multiplicity of other daily forms of structural and symbolic violence. The aim of peace education is to create positive peace by reducing hunger and poverty, bringing about social and labor equality, and eliminating human rights violations.

The second great challenge lies in our relationship with outsiders and with otherness. In a globalized world, with its enormous flows of migrants and refugees, the ability to relate peacefully to others is of vital importance. In this regard, we also need to learn to deal critically with our own egocentrism, logocentrism and ethnocentrism, developing in their place a heterogeneous way of thinking stemming from an appreciation of otherness.

The third challenge that will determine the future of humanity is that of sustainability and the task of educating the world towards sustainable development. In September 2015, representatives of states across the globe met in New York and came up with 17 sustainable development objectives for the years to come. All of these objectives were known to be important, but for the first time they were accepted by the entire community of states. These resolutions were the first step towards a utopia, and raised many hopes. All the objectives aim to reclaim a non-violent relationship with nature and with the earth’s resources, with other humans and with other living beings. These three challenges overlap, and there is no certainty whether and to what extent we will succeed in achieving the progress we all hope for. Lyotard’s skepticism with regard to grand narrations is still highly relevant.

You have also worked on the role of the body and bodily abilities in relation to knowledge and cognitive processes. You have developed a theory of mimesis in order to explain how the body “works” in these processes and how intellectual activities are grounded in the body. The relationship between body and mind has always been a central topic in philosophy (and may be traced back to Cartesian dualism). In particular, it has influenced the history of philosophy through the problem of so-called ‘substance dualism’. Even though one might think that it is an old problem which has been overcome through the latest achievements in the field of the cognitive sciences and neurosciences, its repercussions are still visible in some debates in the field of analytic philosophy, as for instance in the controversy about first or third-person description. How would you explain the relationship between mind and body from the perspective of your theory of mimesis?

By ‘mimesis’, that is behaving or acting ‘mimetically’, I mean forms of productive imitation. In my view, cultural learning is essentially mimetic (see ‘Mimesis, Art, Culture, Society’, Berkeley, 1995). Let me give three examples: learning to walk in the upright position, learning language and learning many of our sentiments (together with their expressive forms).

According to missionaries’ reports and documents from India, children who were brought up with animals crawl and never adopt the upright position. Looking at young children, it’s incredible to watch how much energy they expend to try and get onto their feet like the other members of their family. Children want to be a part of the family, and to behave just like the people they live with and love. As Wittgenstein made clear, language too is learned through active language games. Children take part in the actions and in the language games of the adults around them. Their motivation is their desire to be like the others. Through their perception of the adults’ actions and their participation in these actions, children assimilate themselves to adults, or to their siblings. This is how they learn to behave and how to speak. The desire to behave like the people they love is an expression of the social character of humans. To a far greater extent than in other non-human primates we are social beings who acquire most of our cultural capacity as part of a social process.

In a project, funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) I was able to observe how sentiments towards others are learned and expressed at a very early age. Early interactions between mother and child take on particular significance here. I was also able to show how important the development of positive feelings is for the personal growth and development of human beings.

Many learning processes take place through mimetic actions. In young children, the process of distancing and separation between the child and the world of objects has rarely started to take place. Young children see the world as if it were magic, or animated. Mimetic learning does not only take place by mimesis of other people, however. It also comes about, as Walter Benjamin demonstrated so clearly in his book, ‘Berlin Childhood around 1900’, by means of the mimetic appropriation and elaboration of space, contexts and things. In these processes, children amplify their imagination, create a reproduction of the world around them and embody it. Learning is mostly a bodily function in these processes. What we call spirit – which still has a corporeal element - is gradually developed over time. This early learning is essential for the later success of more complex social and spiritual processes.

The importance of mimetic processes is often underestimated, even though they were already taken into account by Plato and Aristotle. The latter defined the human being as the animal most characterized by mimesis. Research into neuron mirrors today shows how the perception of social action activates in the observer similar processes to those taking place in the person undertaking them. Research into evolutionary anthropology also supports the claim that young children have access to a range of mimetic possibilities which allow them to perceive and understand the intentions of other humans. This ability is unheard of in other non-human primates. In esthetics too mimetic processes play an important role in the way art is received. The iconic nature of an image can be experienced only through mimetic processes and can only be integrated in the imagination through these processes. The same is true for listening to music. Its quality can only be appreciated by means of a process of reproduction and coproduction. Dance can only be learned by practicing it. Explanations and descriptions merely support their learning.

Another area of mimetic learning is practical knowledge. We learn most of our daily actions, such as cooking or driving, mimetically. We assume a reproduction of the practices of daily life and we incorporate them. Mimetic learning is based on the ability of the imagination to exchange exterior modes with interior modes. We can even talk about mimesis as a premonition.

As an anthropologist and a pedagogist, how would you address – methodologically as well as theoretically – the problem of comparativism, i.e. the problem of comparing cultures and different systems of thought in one's research? Your studies usually combine themes crossing different cultures, with special attention to Asian contexts. Where would you draw the limits of such a comparison and how would you describe them, since they also determine the fruitfulness of these studies in the present day?

From a methodological point of view, comparisons are extraordinarily interesting. In order to improve our knowledge we need to work on differences and these can be learned by comparing. In my research in historical anthropology, my enquiries into historical issues have served as a mirror for contemporary life. In this sense I am different from historians within the field of historical anthropology, who are less interested in pursuing knowledge about the present or about themselves in their historical research. What I am referring to, of course, is diachronic comparison, which is a valid source of knowledge. Comparison, however, also plays a role – inasmuch as it is synchronic – in cultural anthropology. In choosing a field of enquiry, for example, selecting a group to interview, comparison plays at the least an implicit role. It determines the reasons for choosing one group within the field of research or for not choosing that group.

In our study of family happiness, which I undertook with many other colleagues, the first thing we had to do was choose three German families and three Japanese ones. The choice was clearly to find families that were different, and certainly not too similar to one another, in order not to limit our field of research. Since we had to visit the families on Christmas Day or New Year’s Day it was not easy to find families willing to admit outsiders into their intimate sphere over the holidays.

The aim of this research, to start with, was not to discover what the members of the families thought constituted family happiness. Rather, it was to observe how some members of the families recreated the rituals of Christmas or of New Year’s in order to make the other members happy or put them at their ease (see Das Glück der Familie, 2011). In focusing on the performativity of the members of the families we followed a principle which placed the perspective of the observer at the center. That is, third person observation. Every Japanese-German team researched one German and one Japanese family in order to understand in what way the members of each family created their wellbeing and happiness. To this end, we concentrated on the performativity of their actions and interactions. As a follow up, we didn’t make comparisons either within the three German families (or the three Japanese families) or between the two different groups. If we had wanted to do so, we would have met with considerable methodological difficulties, which, in their turn, would have had implications in other spheres such as the differences between the languages and the different representations of happiness. For this reason we went down another route, which was anyway comparative. That is, we researched all the families ethnographically. We let the families discuss what happiness means for them and what they did to achieve it, even in discussion groups outside our third person observation perspective. We thus used both third person observations and self-enunciations from the members of the families (first person perspective) in order to build up a more complex picture of the representation of happiness in each family. On the basis of this research, we developed (and this was also possible only by means of an implicit comparison) the following five trans-cultural dimensions of family happiness, its representation and performance.

Religious Practices: A church visit with the German family I was researching (Christmas carols, Christmas stories, repeated and modified in the family), a visit with the Japanese family to a Buddhist temple and a Shinto reliquary in the early morning of New Year’s Eve, after a visit to the family tomb on the afternoon of Boxing Day.

Common Meals: In the German families, sitting around the table, each member was sitting in his or her own chair. Simple food is served, so that there is time to spend time together. In the Japanese families, the food is complicated (especially on New Year’s Eve), prepared by the women with special foods, and many symbolic dishes, which express the wish for a long happy life. In the families we visited women had the task of cooking the food which suited the family taste, and which gave everyone in the family the same sensations.

Gift Exchange: The exchange of gifts played an important role in the German family I and my Japanese colleague researched. Since it was a family of six, the gift exchange and the dialogues associated with this activity took up a great deal of time. In my view, it was not just a matter of the material value of the gifts but rather the significance they played for each member of the family and for the family as a whole. In the Japanese family, gifts consisted simply in small sums of money given by the adults to the children.

Family Narrations: In both families the narration of typical family stories played an important role and contributed essentially to building up the family identity. For this reason many of the stories were told again and again. In the Japanese family, for example, the centerpiece was the grandson’s heart operation that saved his life that had already been told various times and in various forms over the holidays by all the other members of the family. In the German family, likewise, there were several equivalent narrations by means of which family identity was reinforced.

Free Time: The fact that in these holidays there was a great deal of unstructured free time played an important role in both sets of families because it gave time for spontaneous interactions among the members of the family, characterizing the type of holiday and its quality. In the Japanese family, the women played intensively with the children. In the German family there was a great deal of space for individual and collective family discourse, as, for example, when the behavior of children towards their parents was praised.

These five dimensions are trans-cultural, and could only have been developed by means of an implicit comparison between the Japanese and German families. Each ethnographic study provided a specific character of each family, which was an essential finding of the research. Developing the trans-cultural dimensions made it possible to design a representation of the things that not only the families that belong to these cultures do, but also what other families belonging to other cultures do in order to make their members happy. On the basis of numerous discussions that have taken place, for example in China or in Iran on matters relating to the structuring of family holidays, I have become convinced that these five dimensions play an important role in the Chinese Spring Festival and in the Iranian Nowruz holiday, and for this reason they can legitimately be called trans-cultural.

By means of this procedure, which operates by making implicit comparisons, a precise ethnographic enquiry on the peculiarity of every family can be carried out. At the same time, however, the results are translated into a trans-cultural issue. This procedure seems to me to be innovative for conducting research within anthropological-cultural anthropology, which takes into account both the particular and the universal aspects.

One of the most frequently applied categories in many fields of research is “performativity”, which is also a topic cutting across all your fields of study – from anthropology to pedagogy and philosophy. I have two questions regarding this concept: first, how would you describe (and evaluate) the effect of performativity in subjectivation processes? And, second, regarding the relationship between performativity and the concept of medium/media and the transformations that are modifying bodily skills and abilities by incorporating virtual and mechanical elements (just think about the new forms of digital communication), how is this trend changing, in your opinion, the anthropological understanding of the human being? In other words, where can we draw the line between what is “human” and what is not?

I have dealt specifically with questions regarding performativity in the context of my research into the Culture of Performativity (see Kulturen des Performativen). In my view, this concept helps us develop an important perspective in the humanities, especially in pedagogy. What does this mean precisely? With the concept of performativity the significance of the performance in a social sphere is placed at center stage. The body and its gestures also take on particular significance. By stressing performativity, therefore, it is possible to rediscover and research a fundamental dimension for learning processes and training. It has a great deal to do with the active role of the child, which is made evident by the fact that a child actively appropriates his world and doesn’t wait for the world to be explained or demonstrated to him or her. Thus, emphasizing performativity in pedagogy means that learning processes are focused on the capacities of the child.

It is possible to identify a series of important principles for developing a theory of performativity. First and foremost, the ideas of John Austin, according to whom words are actions in certain social contexts. This is the case, for example, when a couple pronounces the words “I do” at their wedding. The word “yes” becomes an action that transforms the rest of their lives. Judith Butler has quite rightly pointed out that when children are referred to as “boys” or “girls” certain expectations are placed at center stage, in a clearly performative manner, and these words contribute to developing their gender identity. The arts, with their concepts of performance have also contributed to our knowledge of human behavior, namely the fact that it cannot be reduced to a question of language, or to rational actions. All social interactions take place through the human performativity of elements, and the significance of this has long been misunderstood. Performativity has a lot in common with the mimetic transmission of culture we already talked about. Performativity plays a central role in the interaction that takes place among human beings. For every person it expresses something that could not be expressed in any other manner and that is of great importance in the way humans represent their own identity (see Die Pädagogik des Performativen, 2007).

Performativity also plays a significant role in new media, as a lot of our research has shown. In this case it is a form of performativity produced through media, such as images or movements, that play a role in computer games as well as in other actions online. In my view, the performativity of human actions in the media is represented in different ways. Its expression in new media is certainly determined, but in no way superseded by the media’s characteristics.

Could you briefly outline the themes and problems at the center of your current research?

If you’re asking me what I am researching right now, the answer is, just as before, some of the fundamental anthropological questions. After bringing to an end in 2014, at least for now, my years-long research into the imagination (see Bilder des Menschen. Imaginäre und performative Grundlugen der Kultur, 2014), and, in 2016, my equally long research into alterity (‘Exploring Alterity in a Globalised World’, Routledge, 2016, and Begegnungen mit dem Fremden, Munster, 2016), I have also been working for years on the significance of other forms of knowledge. Together with a colleague I have organized a couple ol lectures on of the Knowledge of the Body (Körperwissen) at the Freie University in Berlin (see Paragrana, 1/2016). I have also organized, with a Brazilian friend, a far-reaching interdisciplinary and transcultural conference in Sao Paolo on the subject of Wisdom: An Archeology of Forgotten Knowledge. (Weisheit. Zur Archäologie eines vergessenen Wissens), the findings of which will be published in Brazil in 2016. Moreover, after a research period at the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute for Advanced Studies in New Delhi, I launched and conducted a conference on the topic of Scientification and Scientism in the Humanities, where we discussed the problems stemming from the scientification of our lives and our world and the way non-scientific knowledge is evaluated socially. This conference was an ideal continuation of research I had undertaken in 2013 with a colleague at the Russian State University for the Humanities (RGGU) in Moscow on the significance of the humanities in society (see Paragrana 2/2015). At the moment together with a friend I am preparing a conference at Stanford University to be held in the Spring of 2016 where we plan to analyze the significance of “Repetition, Recurrence, Returns” (Wiederholung). Finally, together with several colleagues, we are planning to publish a compendium on the significance of implicit knowledge (Schweigendes Wissen, Weinheim, 2016). In this handbook we will look into the significance of implicit knowledge in education, training and socialization. To conclude, I would like to mention an interdisciplinary project I am engaged in with colleagues from the fields of psychoanalysis, dance science and linguistics called “Rhythm, Balance and Resonance”.

Since 2011

Since 2011