The pig and its history, Pier Paolo Pasolini, the history of towers in the West, Philip K. Dick and science-fiction literature, the films of Andrej Tarkovskij and Rossellini, the cultural history of calendar formation. And: metaphors of death, rites and myths in the context of historical anthropology, ethical, aesthetic and cultural models of Western history. What might sound like entries in an impossible and ironic encyclopedia in the spirit of Borges and Foucault are in fact all subjects of some of the courses held and the books written over the past few decades by a man who in Germany is considered the Kulturwissenschaftler par excellence: the Austrian Thomas Macho. What is a Kulturwissenschaftler? To understand it, we need to dig into the history, as well as the etymology, of the German term Kultur, and we will ask Macho himself to do just that during the interview. For now, by way of introduction, a brief clarification: if we wanted to translate Kulturwissenschaftler literally into Italian and thus into English, the closest rendition would be “scienziato della cultura” or “scientist of culture.” But we must keep two points in mind: first, that in German the term Kultur indicates a broad and complex semantic field, which comprises both “culture” and “civilization,” as well as many other concepts deriving from them. And second, that, historically, in the field of human sciences in Italy, ever since the famous translation of the title of Sigmund Freud’s essay Das Unbehagen in der Kultur into Il disagio della civiltà, the German word Kultur has often been translated as “civilization.”

Macho, now sixty-three, with a doctorate in musicology and certification to teach philosophy as well as a few hundred books, articles, essays and curatorships under his belt, has since 1993 taught “the History of culture” [Kulturgeschichte] at one of Germany’s oldest and most prestigious universities, the Humboldt Universität in Berlin. If we look closely at this incredibly prolific author’s body of work, even just from a thematic point of view, we can clearly see why Macho is currently an essential reference point for anyone who deals with the history of culture. In fact, in decades of research in the most disparate of thematic fields, he has managed to bring together sound historical and philosophical methodology with factual analysis of some of the themes (as vital as they are all too often relegated to the margins) located at the intersection between human sciences and natural sciences. Hence his writings and courses on themes of death, solitude, animality, rituals, suicide and religious conversion. These are also the cardinal themes of Kulturwissenschaft, the science of culture which, poised on the line that unites and separates philosophy, anthropology, psychoanalysis, sociology, media theory, art history and ethnology, attempts to carry out a global analysis of the macro-themes of which each of these disciplines can offer only (necessarily, for intrinsic methodological reasons, although this is not in itself a negative factor) a partial analysis.

These subjects, so existential, so essential and so incredibly neglected by what we call “scientific” research, have been analyzed by Macho using a methodology that has now become seminal in the field of sciences of culture in Germany. Macho’s methodological process, in his writing as in his thronged university courses, is illustrative for an understanding of how a scientist of culture differs from a philosopher, a sociologist or a scholar of literature, even while embodying – in part – all of these figures. The preliminary operation Macho normally starts with when beginning a research effort (an operation he himself defines as “casuistry”) consists, initially, of collecting a large amount of data, events, descriptions, case studies, visual documents, video, audio, film, literary narrations and artistic expressions that focus on the theme that is the object of his research. In this first phase, then, the scientist of culture works with philological, historical and anthropological methods: archival and - whenever possible - field research.

In the second phase, the materials are analyzed in relation to the expressive medium (written, visual, film, audio) and divided according to historical and cultural areas concerned. This part of the research lies within the sector of media studies (and its relative sociology) and sociology in general. Finally, the materials are assembled around a central theoretical thesis, or a recurrent question, which thematically and methodologically permeates the study, both as an underlying question and as an arrow pointing towards the conclusion from the outset. This theoretical and methodological framing is the most authentically philosophical thing that Maco in particular, and the scientist of culture in general, does, or should do. So we have what Macho often calls, in his essays, books and courses, a “Kulturgeschichte von …”, that is, “a cultural story of …” a theme.

So, to clarify the modus operandi of a cultural historian and “scientist of culture” like Macho, we must first of all understand the peculiar method and the specific object (or rather, the objects) of research of this discipline – Kulturwissenschaft, the “science of culture” – which has not yet been codified and classified in the spectrum of Italian academics. Beginning with this thematic and methodological clarification, we asked Macho to outline the path of his research and study, the themes that have most fascinated him, his ties to Italian theory and culture, and his future projects, in the belief that the best way to understand and spread awareness of the science of culture is to give the floor to one of its greatest living practitioners.

(translated from Italian by Theresa Davis)

Thomas Macho

AL: Professor Macho, you have studied musicology and you have written your Habilitation on metaphors of death. You are a philosopher as well as a Kulturwissenschaftler and since 1993 you work at the Humboldt University as a professor of Cultural History. In many of your publications you deal with the works of Martin Heidegger, Simone Weil, Jacob Taubes, Ludwig Wittgenstein, or Jean-Paul Sartre. Furthermore, you have written about rituals, visual images, art, media, technology, literature, and film. Could you explain to the international audience – to whom the figure of the Kulturwissenschaftler is probably unknown – which research topics bring together these heterogeneous themes? Simply put: what is it that a Kulturwissenschaftler ‘does’? How can (s)he be characterized?

TM: Kulturwissenschaft is a field of research that in the third decade of the twentieth century emerged in the wake of neo-Kantianism and Lebensphilosophie. Authors that may be associated with this field are: Walter Benjamin, Ernst Cassirer, Georg Simmel, but also Max Weber and Johan Huizinga. In 1933 the Dutch cultural historian even wrote a review of Aby Warburg’s collected works and gave it the title ‘Een cultuurwetenschappelijk laboratorium’ (‘A laboratory for the science of culture’). At that time Kulturwissenschaft was an interdisciplinary European network that could also be associated with the foundation of the French Annales as well as with the history of psychoanalysis, the beginnings of research on sexuality, ethnology, and film theory. In the US, however, William M. Handy, commissioned by the American Society of Culture, published a four-volume work titled The Science of Culture. This work deals with the rules for correct behavior, such as table manners, matters of conversation, fashion, dance, letter writing, appropriate public appearance, and the etiquette between men and women. Today, such a work may be classified as a guidebook. During the 1960s several Eastern European states re-established Kulturwissenschaft as a scholarly free space that was opposed to the confines of a dogmatic Marxist-Leninist philosophy and sociology. In the same period, the Anglo-American world witnessed the heyday of what is called ‘Cultural Studies’. In 1964 Stuart Hall and others founded the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. Since then the study of everyday life became a principal thread and it forms an important precondition for the study of the world of things (Dingwelten), which today finds its strongest representative in Bruno Latour. But in Berlin it was in 1993 – in the wake of the so-called Wende – that Kulturwissenschaft as a field of study linked to the field of aesthetics was founded after the appointment of professors Hartmut Böhme, Christina von Braun, Friedrich Kittler, and myself. Research themes that since then became central are, amongst others, media history, the theory and history of cultural techniques, transformations of antiquity, and gender studies. Moreover, there were fruitful attempts to renew the interdisciplinary and transnational orientation of Kulturwissenschaft: many of its methods have found their way into literary studies, philosophy or art history – especially since the much discussed ‘iconic turn’ in the Bildwissenschaften.

AL: Many thanks for this historical reconstruction of the origins of the German Kulturwissenschaft, especially in relation to Anglo-American Cultural Studies. Continuing this line I would like to ask you if, in your opinion, there is a specific difference between the German and Anglo-American variety when it comes to research topics? And, more specifically, is there a methodological difference between the two? With the concept of ‘Cultural Studies’ in mind, I would also like to ask you if you deem the singular Kulturwissenschaft or its plural form Kulturwissenschaften more adequate? Simply put: must one speak of Kulturwissenschaft or of Kulturwissenschaften?

TM: Both in matters of content as well as method, there are many intersections between Kulturwissenschaft and Cultural Studies. However, it is true that Cultural Studies is more interested in contemporary issues, while Kulturwissenschaft also deals with questions of longue durée. In regard to the question of naming the discipline in singular or plural: in the German speaking parts of the world institutes for Kulturwissenschaft in singular, such as those in Berlin, Bremen, Marburg or Tübingen, can be opposed to the research centers, departments or faculties that prefer the plural. The difference between singular and plural, which is only occasionally overcome by the adjective kulturwissenschaftlich, refers to the respective curricula and research interests of the staff. As an academic discipline, Kulturwissenschaft does not only refer to a tradition and a scientific identity, but also to the consecutive education on a Bachelor and Master level up to a PhD and Habilitation. The foundation of research centers or departments of Kulturwissenschaften, in contrast, follows mostly a strategy in which existing disciplines are integrated in a spectrum of cultural study and research. The affiliation with Kulturwissenschaften then results, more or less by chance, from the question which disciplines are interested in contributing to such a programme and field of research. In any case, I believe that the debates on the correct name stem from a shift: the critical question of the singular or plural does not concern the sciences, but a concept of culture which is all-too-often being essentialized (like it was formerly done with God or Being). There are many cultures, irrespective of whether we view them from a relativist perspective or from a critical universalism. In the German debate about the concepts Kultur or Zivilisation, Johan Huizinga opted for the Italian camp: he saw Dante’s civiltà as the “sublimest of all definitions of the phenomenon of culture.”

AL: Your books on death (Todesmetaphern [Metaphors of death] and Die neue Sichtbarkeit des Todes [The new visibility of death]) have become key publications in the field of thanatology. However, in Italy this discipline remains – apart from the recent and valuable studies by Davide Sisto and Marina Sozzi – somewhat marginal. Why is it -from the perspective of a Kulturwissenschaftler - important to study death? What can the Humanities reveal us about death?

TM: Death remains an existential enigma, also for the ‘Humanities’, which operate beyond religious rituals and hopeful consolation. This mystery stems from some kind of division of the subject: the one who tries to imagine what it is like to be dead could always only ignore the imagined, not the one who imagines. In twentieth-century literature and philosophy death has become a dominant theme, at the very latest since Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. In the Kulturwissenschaft on the other hand, one is concerned with the history and comparison of cultural attempts in finding an answer to the mystery of death: in poetic or visual anticipations of one’s own death, in mourning or in remembrance. Since a few years Kulturwissenschaft witnesses the emergence of a very important research object: i.e. the emergence of a new death and mourning culture beyond hope for immortality and also beyond the once very common repression of death. This emergence is not only articulated in new funerary and remembrance practices, but also in biographical testimonies, documents, novels, films, or TV series. Above all, it is visible in the various discourses one finds in social media.

AL: Recently you have given a course on the topic of suicide. Could you please explain to us how a Kulturwissenschaftler approaches such a topic? Which new perspectives could (s)he open up beyond the more common sociological or psychological interpretations of suicide?

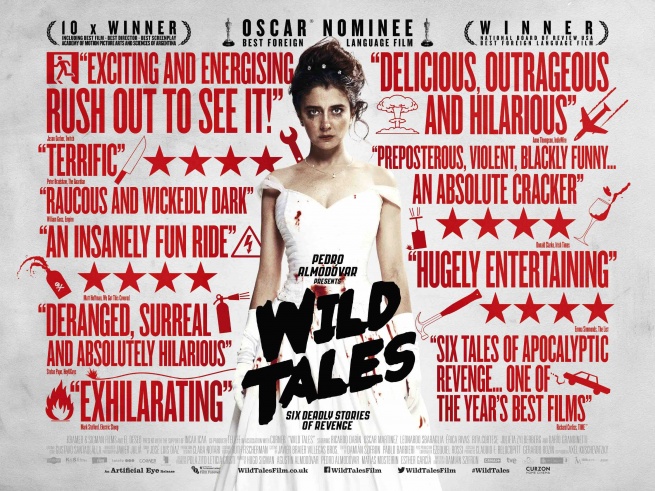

TM: It was at the end of the Second World War at the latest that a remarkable revaluation of suicide – on the one hand as a process of breaking taboos, on the other as the extension of a technology of the self, in the sense of Svenja Flaßpöhler’s Mein Tod gehört mir (2013) – took place in several cultural fields: in politics (suicide as a form of protest or murder-suicide), in law (the liberalization of euthanasia), in medicine (assisted suicide, palliative care), in philosophy and aesthetics (literature, visual arts, film). In the nineteenth century suicide was mostly dealt with as a sin, a disease or as some kind of sacrifice. But this twentieth-century revaluation has opened up a vast field of cultural research, especially because since the early nineteenth century the cultural roots of suicide – take for instance the so-called ‘Werther Fever’ – had been heavily discussed. Central to a cultural inquiry into suicide are two questions: 1. The question of historical and actual appearances of suicide cultures, and 2. The question of resonances between the aforementioned fields of politics, jurisdiction, aesthetics, and philosophy. And, up until now, those questions have been discussed with mainly film and computer games and their influence on suicide attacks in mind. In the UK, people discussed the postponement of the premiere of Damián Szifron’s Wild Tales (from 2014) till 27 May 2015, because in the first episode of the film the flight attendant Gabriel Pasternak locks the door to the cockpit so that he could bring the airplane – in which all seats are taken by people that have done harm to him – to crash above his parents’ house. The crash of the Germanwings flight 9525 in the Alps in southern France took place, as we know, on 24 March 2015. By the way, Wild Tales premiered in Germany – under the title Jeder dreht mal durch! – already on 8 January 2015.

AL: In addition to other topics you have also been interested in catastrophes, not least in the sinking of the Costa Concordia. What did you find interesting about this history?

TM: As you know, most forms of political theology also deal with the end of the world, the apocalypse. Even in Jérôme Ferrari’s novel Le Sermon sur la chute de Rome, which was awarded with the Prix Goncourt in 2012, this topic was extensively dealt with, especially in regard to St. Augustine. I believe that the sinking of the Costa Concordia, on which Jean-Luc Godard has filmed part of his Film Socialisme (2010), may be seen as an apocalyptic warning sign, not least since some months after the accident the centennial of the sinking of the Titanic was celebrated. Without a doubt, the rhetoric of catastrophes is one of the most pertinent themes of a Kulturwissenschaft as a discipline for a diagnostics of our time. The Costa Concordia is in Godard’s film also a symbol for the crusades and the brutalization of the Mediterranean spirit, which in the 1940s was described by Albert Camus or Cesare Pavese as the very source of European identity; already in the first few minutes of the film a woman cries out with heartfelt groan: “And as we have, once again, given up Africa”. Only a few months after the accident with the Costa Concordia this became reality right before the island of Lampedusa, where with the sinking of a ship 300 people died, while fleeing from for starvation and destitution in Africa.

AL: The most recent of your great books is one on economical themes. It was published as Bonds: Schuld, Schulden und andere Verbindlichkeiten [Bonds: Blame, Debts and other Liabilities] in 2014 and comprises a large series of perspectives and discussions on the different aspects of the ‘economical ordering of our present’. Could you please explain the basic idea behind this book? In what way could, in your opinion, a cultural perspective contribute to an understanding of our contemporary economical situation?

TM: That book is the result of a conference that was organized in December 2012 and at which many different perspectives on the financial crises and its consequences were discussed. Not only economists took part; philosophers, ethnologists, historians, sociologists, psychologists, reporters, and artists participated as well. My own contribution dealt with the question of whom we can owe something because we are owned by him and belong to him: the forefathers and the family, a god and a church, the state, a bank or ourselves. I was inspired by a critique of the relational systems of genealogy and the project of an existential economy, which, so to speak, respects the rules of ‘vertical migration’, rules of birth and death. Not for nothing all of our well-known travel documents misrepresent the place and moment of the passage through which we come into this world only to leave it a bit later. Two claims may be drawn from the concept of existential economy: the demand for a fundamental critique of inheritance (as, for instance, Thomas Piketty has recently formulated), and the demand for the introduction of a basic income as a Begrüßungsgeld [a ‘welcome fee’] that makes up for the fact that no one has voluntarily decided to come into this world. Fundamental to civil rights (oder: constitutions) is the assertion that we are all born equal and free. Boldly put: just as naked as we will die. We must also think about why some children come into this world with a rich bank account, while others are born into poverty and destitution, often with debts that take a lifetime to redeem. Those themes I have also tried to analyze in a longer essay titled Das Leben is ungerecht [Life is unfair].

AL: You have also worked a lot on Italian culture, art and philosophy: from Pier Paolo Pasolini to contemporary Italian philosophy or the so-called ‘Italian Theory’. Do you think that today we may speak about an Italian Kulturwissenschaft? In which aspects and authors of Italian culture are you mostly interested?

TM: There has been an Italian Kulturwissenschaft since long, even though it may not have been designated as such. Belonging to such a circle of scholars are Paolo Mantegazza, Camillo Sante de Sanctis, Ernesto de Martino, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Carlo Ginzburg, to name but a few. I also believe that the debates over ‘Italian Theory’ will help the emergence of new forms of Kulturwissenschaft in Italy, especially when the differences between several concepts of ‘life’ and their corresponding forms of biopolitics – ranging from Giorgio Agamben to Roberto Esposito – can be elaborated upon as a critique of genealogical ordering systems. Not for nothing have I taken the liberty to associate the current debt negotiations with a passage from Mario Puzo’s novel Godfather: “I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

AL: Your most recent book deals with the cultural history of pigs: how did you get to this subject? Could you perhaps situate your work in the field of Animal Studies?

TM: There’s almost no other field in which the critique of the demarcation line between nature and culture can be brought to the fore with such clarity than in the sketch for a cultural history of animals. Since the early 1990s, I have been concerned with the topics of the current Animal Studies. I have published essays on the history of domestication, the cultural transformation of birds into angels, the devil’s accompanying animals, pastoral practices or dietary behavior and nutrition. One who thinks about life (Leben) must also think about food (Lebensmittel). And when it comes to this topic it was probably Pasolini who took the most radical stance – simply put: capitalism as eating disorder – not only in his essays and films such as La Ricotta or Teorema, but also in his stage play and film Porcile. The pointe of this film about a pig barn, one that I also try to develop in my portrait of pigs, can easiest be summarized in that line from Elias Canetti’s Masse und Macht: “That what is eaten eats the one who ate it.”

AL: To end with: What are you currently working on? What future projects do you hope to develop?

TM: In the following weeks I am going to work on the edition of a collection of short texts on Opera; and I have just finished a concept for an extensive study of suicide cultures. On my desk, however, lies the German translation of the dissertation that Susan Taubes – under Paul Tillich’s supervision – has written on Simone Weil; and also there is the first volume of Johan Huizinga’s correspondence (with Luigi Einaudi among others). In addition to that I dream of writing some essays on cinema – a big passion of mine – pieces on Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky, or the Dardenne brothers.

(translated from German by Geertjan de Vugt)

Since 2011

Since 2011