In 1964, Renzo Zingone decided to found and build a new town on farmland in the province of Bergamo. Zingone was a wealthy businessman from Rome who owned the Banca Generale di Credito and had made his fortune mining gold and copper in Venezuela. He had already built the Zingone quarter in Trezzano sul Naviglio just outside Milan. In both cases the choice of name – Zingonia – had been dictated by Zingone senior who, in a letter dated 1930, had advised his two sons, Renzo and Corrado, to “always strive to valorize the family name”.

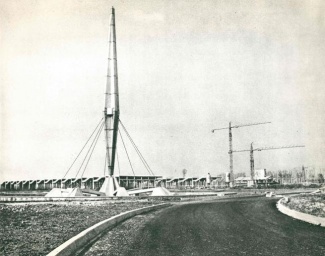

Zingonia, Missile

Both the Zingone quarter and the new town Zingonia, were designed by the architect Franco Negri, born in 1923, who graduated from the Milan Polytechnic in 1956. The foundation of both projects was the prefabricated industrial depots produced by the family company, Zingone Structures, which in Renzo Zingone’s mind were to become the productive heart of the new settlement. There was an essential difference between the two designs, however. The Zingone quarter was to assimilate the already existing industrial and productive businesses in the Milanese hinterland. In the new town, Zingonia, by contrast, the industrial warehouses were supposed to become the vanguard for a vast operation aiming not only to radically transform the outskirts of Bergamo, but also alter the customs and actions of the life of its inhabitants.

Renzo Zingone. Zingonia

At the basis of the Zingonia concept there was an aspiration which was without a doubt financially motivated, but also embraced a fundamentally utopian vision. Planning residential areas and industrial facilities in one area, thereby potentially solving the problem of commuting, was an attempt on Zingone’s part to modify profoundly a deeply rooted social structure of Italian society. Added to this, Zingonia designated green areas for sport and leisure pursuits, which provides further evidence for the claim that this new town was not very far from the new cities theorized twenty years or so earlier in the Athens Charter (Charte d’Athènes) by French urban planners headed by Le Corbusier.

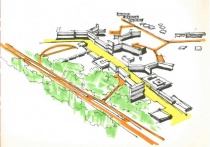

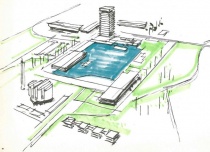

Zingonia, Splint, Swimming Pool, Cinema

Yet, in reality, what happened is that the new social and urban model, predicated on American style mobility both in labor and in housing, situated in an area that was labeled as ‘depressed’ by Italian legislation, soon met with incredibly strong resistance. It was the internal migration from the South of Italy, rather than the reallocation of productive forces from Milan or Bergamo (as Zingone had hoped), that provided the labor force for most of the businesses and factories that eventually moved there.

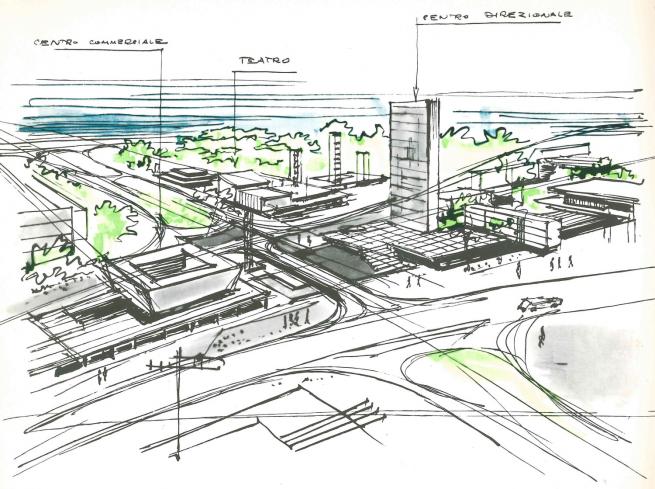

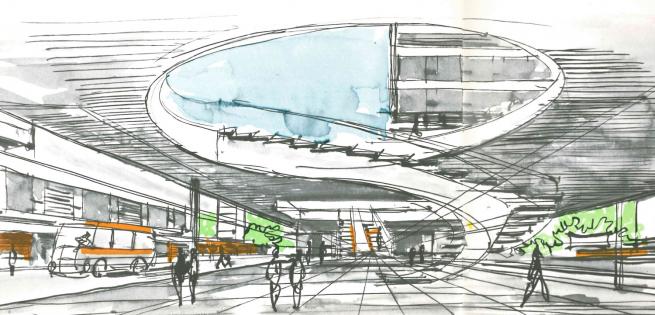

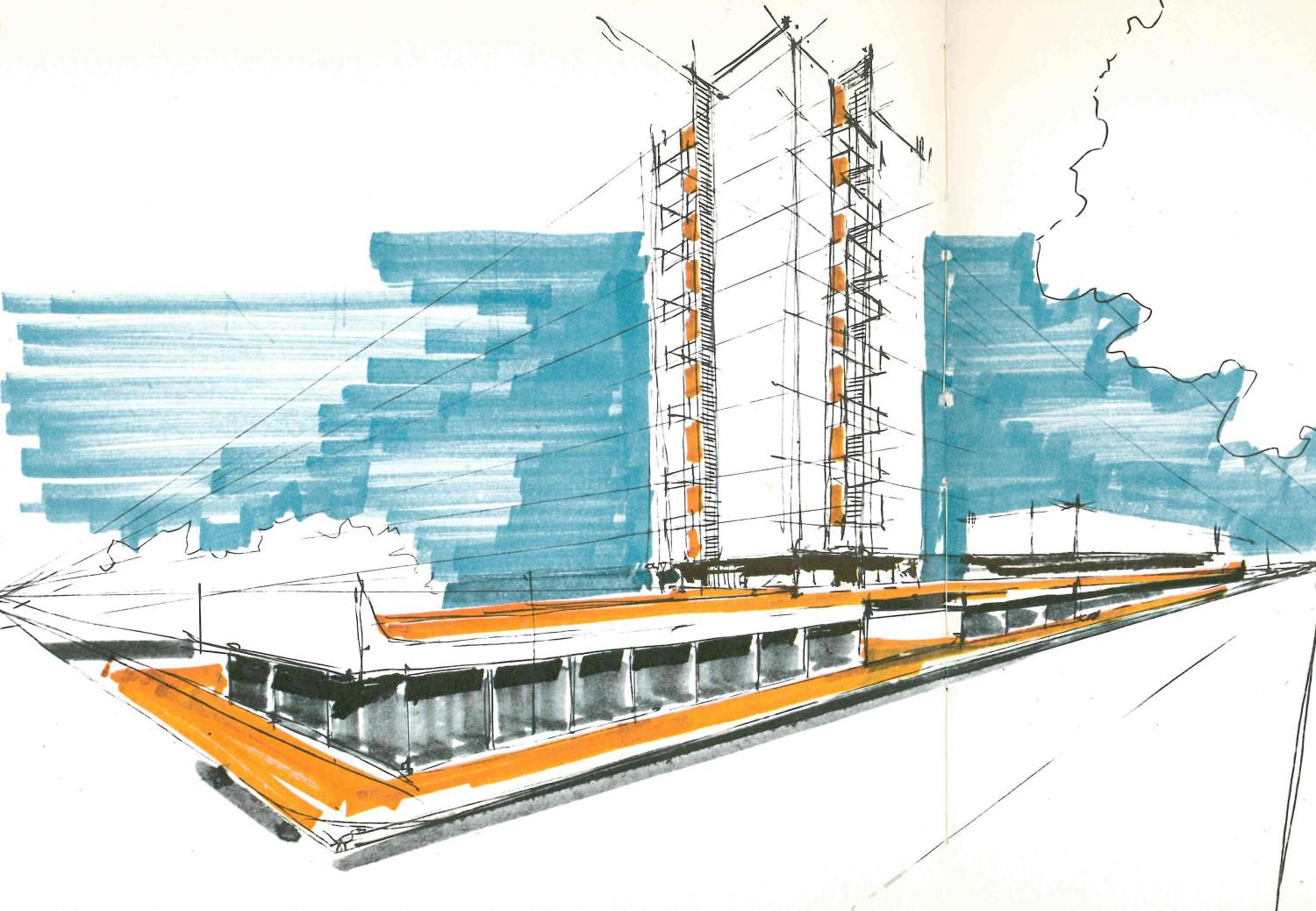

The blueprints for Zingonia reveal the full extent of its founder’s utopian dream, which, unsurprisingly, was never fully realized. These drawings are presented in their entirety in this new Italian edition (Zingonia, la nuova città, Luca Astorri, Marco Biraghi, Matteo Poli eds., Lettera 22, 2014), originally published by the family house, Zingone Iniziative Fondiarie in 1965. The plans are lightly sketched out and are not signed, though they can be ascribed to Franco Negri in terms of their conception. They are rapid visualizations which, on one hand, reveal interesting influences from the recent past (from Le Corbusier to Smithson, including Soviet architects from the 1930s and Mies van der Rohre) and on the other, prefigure architectural solutions still in the future, in particular designs by Rem Koolhaas and OMA).

Zingonia, Shopping Center

This Lombardy version of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, commissioned by Zingonia, envisaged skyscrapers and residential blocks, detached family houses and shopping malls, industrial areas, theatre and public spaces - at least in the drawings. The dream vision was that of a modern city with 50,000 inhabitants, an Italian Brasilia, with a heliport and connections to the nation’s motorways by means of the Milan-Venice highway close by, and links to the great rivers of the north by means of an artificial navigable canal equipped with a harbor and free port.

The failure of the Zingonia utopia, however, was not only the result of the gap between the city as it had been imagined at the drafting board, and the reality of the years that followed. It had been utopian in itself –especially when compared with today’s cities – to have imagined a city built from scratch with the sole force of one businessman behind the project. Zingone always referred to his activism as “following an ideal” or as a “vocation”. His self-described profession – “city builder” – is itself an invention. There were illustrious precursors of this invented profession in Italy, including Adriano Olivetti. To follow, one stands out in particular: the young Silvio Berlusconi.

In 1960s Italy, the idea of investing vast amounts of capital in a project as ambitious as founding a new town was not entirely unthinkable or rash, especially if you had the wherewithal. Zingone cannot be blamed for the incongruity of the project or for its recklessness. What he could be held responsible for, however, was not having spotted its fatal flaw in administrative terms: the fact that the new town was planned to cover territory in five different city councils. His mistake was to think like an entrepreneur and imagine he could found the new town without involving local politicians, who were, of course, the missing link in terms of managing and controlling public goods. His other mistake was, more in general, to have failed to anticipate – as any good businessman would have done - the change of political tide after 1963, when the economic boom was held back by the first wave of strikes and frequent changes in government.

Having said this, construction started apace, and the first inhabitants of Zingonia came to live in the residential districts between 1965 and 1966. It became immediately clear that the ambitions of the early blueprints had been curtailed. Not only was the project much smaller in scope, the quality of the single buildings was also sacrificed. Negri unsurprisingly considered Zingonia one of his less successful projects and the one he liked least. The only parts to survive the original drawings were the industrial depots, built in rows according to three different typologies – Bergamo, Rome and Vittoria – depending on their size and characteristics.

The proliferation of these depots, which was beyond expectations, was enough to produce an immediately recognizable ‘brand’ style and became the distinctive feature of the urban landscape of Zingonia. In addition to these warehouses, residential blocks were built, as well as detached family homes, a sports center, a cinema, a hotel, a hospital and a church (with a later project signed by Vittorio Sonzogni). The fountains and sculptures (including one drawn up by Mario Radice and Ico Paris which never saw the light) were the only decorative elements planned for the new town. The projected 50,000 inhabitants were reduced to a few thousand, even at the time of greatest expansion. Only the wide avenues and the street names bear witness to the grandeur that never was: names of cities, capitals, continents, or flowers, while the residential areas bore the names of girls (Anna, Athena, Barbara, Bettina).

Zingonia, Plate

In the end, the residential areas were the ones called upon to bear witness to the Zingonia project over the years: the best and the worst. The buildings were solidly constructed and a certain amount of attention was paid to the quality of the common areas. The apartment blocks were well spaced out and the 14-floor Verdellino tower was well built. The six Ciserano towers, on the other hand, as well as the other two residential complexes, were cheaply put together with much less care. Having started out as a symbol of the kind of progress the new town of Zingonia wanted to emblematize, these buildings came to incarnate the socio-economic and physical decrepitude they themselves represented.

Before this decay set in, however, it is important to note Renzo Zingone’s exit from the scene. The eponymous hero of the Zingonia drama was understandably discouraged by the downturn of the Italian economy, disappointed by the inadequacy of the local political class, and irritated by the increasing pressure exerted by political parties. At the same time, he was attracted by more lucrative possibilities across the ocean. Construction, and the subsequent commercialization of Zingonia properties, passed into the hands of a company called Coima, founded by Riccardo Catella in 1973. This change in ownership did little to improve the situation. Neglect and lack of maintenance work in the residential buildings spelled the beginning of the end. The apartments were progressively abandoned and then sold off cheaply, or occupied by squatters. Recent proposals include their total destruction and rebuilding.

Today 80 percent of Zingonia’s apartments are occupied by immigrants from 40 different countries of origin. However, the productive capacity of the new town’s industrial sector is high, with some points of excellence, thanks in part to the same immigrants who provide the workforce. The situation is mixed and contradictory, as is real life. Real life here is as far away from utopia as anyone could imagine, but no more than any utopia can ever expect to resemble real life.

This is perhaps what makes Zingonia so interesting and emblematic. It is a mirror in which – like in a neo-realist Italian film which swerves unexpectedly from the dramatic to the comic – all the vices and virtues, all the impulses, ambitions, fragilities, illusions and disillusions are reflected, alongside all of the human features, social trends and tensions that have pervaded Italy over the last 50 years. The gap between the initial blueprints for the new town and its final destination (or at least today’s point of arrival) is precisely what separates Italy as it was in 1964 from Italy in 2015. Similarly, both the dream and the reality – however extreme or exasperated - represent the two Italies they are the product of. This is why the story of Zingonia is worth exploring both as a utopia and as a lesson in life as it really is. Both are irreconcilable faces of the same fascinating and terrible mystery that is Italy.

Z! Zingonia Mon Amour was part of the exhibition Monditalia in the XIV Venice Biennale Internazionale di Architettura. The exhibition was curated by Argot ou La Maison Mobile and Marco Biraghi (with Maria Elena Garzoni, Hiroyuki Kakiuchi, Anton Kotlyarov, Giulia Maculan, Giacomo Mezzadri, Nicolò Ornaghi, Riccardo Radaelli, Giulia Ricci).

Since 2011

Since 2011