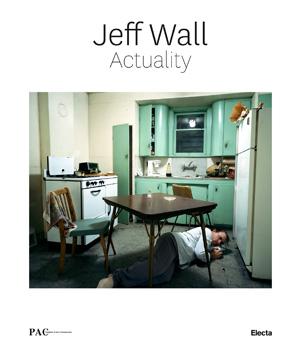

Retrospectives of contemporary photographers have only been hosted in contemporary art galleries in the past ten years, on a par with monographs of other visual artists. One of the better known examples was the retrospective of the Canadian photographer, Jeff Wall, held at Tate Modern and MoMA in 2006 and 2007, and later on show at Milan’s PAC art space with a smaller selection of works.

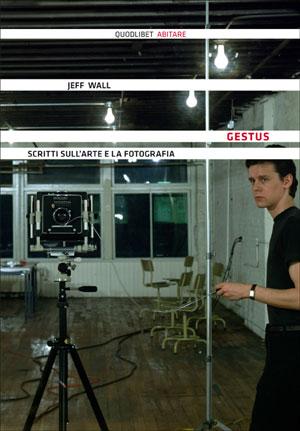

Thanks to the efforts of Stefano Graziani, Italians can now read Wall’s most important writings, collected in an anthology he edited, published by Quodlibet (Gestus. Scritti sull’arte e la fotografie, 2013). Personally I would have added Depiction, Object, Event, published by Afterall in 2007, but nevertheless the anthology contains some of the most important and influential texts on contemporary photography in the last thirty years. These include Dan Graham’s Kammerspiel (1982), and Signs of Indifference: Aspects of Photography in (and as) Conceptual Art (1995). In Sign of Indifference, Wall offers both a photographer’s and a critic’s interpretation of photographic practice in the 1960s, which has been much debated both because it is regularly cited by historians of art and photography, and because it has been accused of being an impartial account.

What happened in this period that was so important for the cultural history of photography and for the way the medium was perceived? While photography was invented in 1839, Douglas Crimp suggests, it was only in the 1960s and 1970s that it was discovered, exhibited, researched and collected by critics as well as by contemporary artists. In France, during the same few years, articles which are now classics were published and disseminated, such as Roland Barthes’s semiotic text The Rhetoric of the Image (1964), and André Bazin’s Ontology of a Photographic Image (1967). Photography, in this period, was freed from the archives where it was destined to remain, and became part of the lettres de noblesses moderniste. Photographs migrated from the musty library rooms where they were held prisoner onto the walls of contemporary art museums. Moreover, the medium entered the international art circuit, and became part of important collections and trend setting institutions.

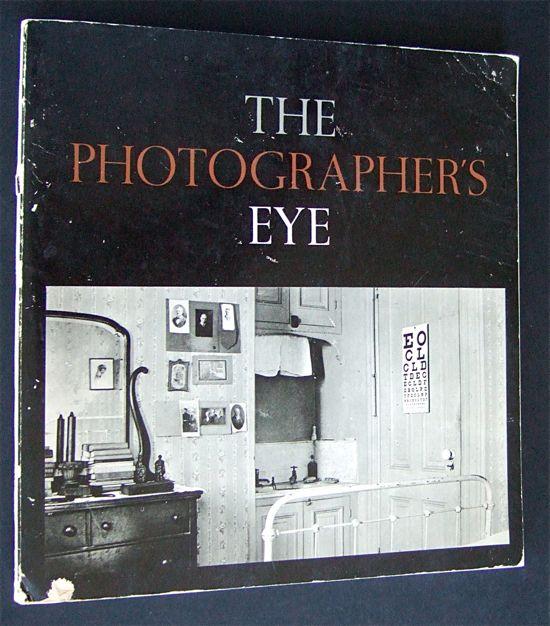

The process was gradual. Even cities at the heart of the art scene such as New York were indifferent to photography at the time. One of the first to react at an institutional level was John Szarkowski, photography curator the Museum of Modern Art from the 1960s to the 1990s. His first show was The Photographer’s Eye (1966). Szarkowski contributed to establishing an esthetic and formal value for photography by adopting the same categories used for fine art, rather like the pictorialist photography of Alfred Stieglitz. This legitimation marked the historic passage from photography to photographic art, from the sphere of documentation to that of esthetics, from illustration and information to the autonomy of fine art. At the same time, however, it hindered the construction of a socio-political context, the circulation of images in the press, the potential revolution of photography as a mass medium. In short it reduced the impact of photography’s impact in the 1920s and 1930s as an allegory of the capitalist mode of production.

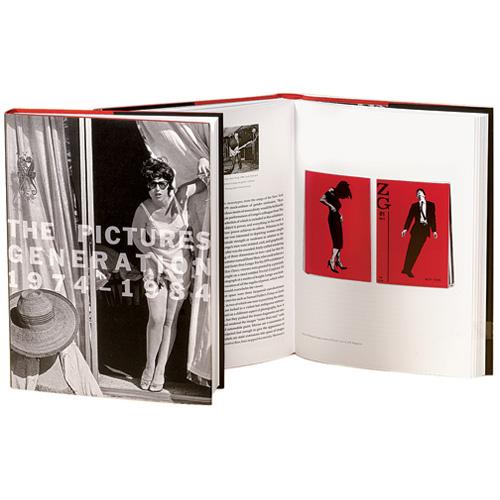

In the 1970s, when Susan Sontag was writing her articles later published in ‘On Photography’, the debate returned to the production, circulation, dissemination, consumption and power of photography, to the construction of its social meaning, the ideological and political effects of representation, the relationship between photography and a society based on showmanship, and to questions of subjectivity and agency. What Craig Owens and Rosalind Krauss called ‘the discursive space of photography’ or the ‘photographic’ was again the object of the debate: a form of representation that gives itself together with its reproducibility, and is therefore reluctant to any form of modernist recovery. The term ‘pictures’ was used as early as 1977 to define the postmodernist practices of appropriation and re-photography. A ‘picture’ denoted something more generic than a photo, less restricted to a specific medium (painting, drawing, sculpture, photo, film, performance). The name “Pictures Generation” – John Baldessarri, Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Sherrie Levine, Richard Longo, Richard Prince, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, Philip Smith – was later coined at an exhibition held at the Metropolitan in 2009.

Forme tableau/Reportage

What was Jeff Wall’s position? His work teems with references to the history of painting, and so I would not hesitate to answer that Walls opted for the term ‘photo’ rather than ‘picture’. Jean-François Chevrier called it a forme-tableau, that is a photograph conceived as an image to be hung on a wall which requires a wall exactly as a painting does. In his view, photography did not become pictorial, it simply inherited the typical problems of modern art. This interpretation was re-launched by the historian of art, Michael Fried, with his usual acumen. His idea of the ‘photographic turn’ was developed 1996 when he met Wall in Rotterdam and realized they shared the same preoccupations about art.

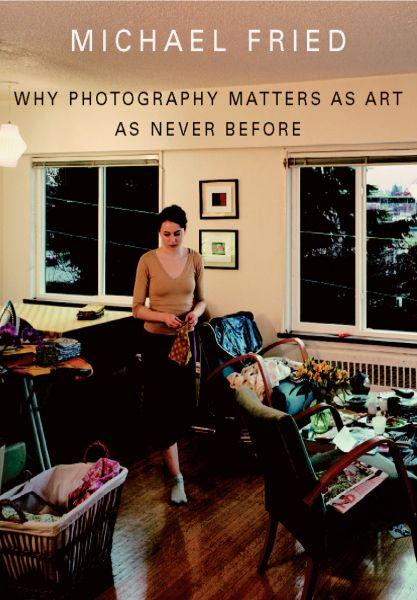

Their meeting marks a return to the modernist experience, as Fried noted in a book with the unequivocal title, ‘Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before’ (Yale University Press, 2008). This work is a critical revision of postmodernism through photography. That is, by means of one of the very mediums that most contributed to postmodernism. The expectations of modernism frustrated by a minimalist sensibility, Fried argues, had been at the heart of photographic research since the end of the 1970s. He cites three points in support of this: large formats, the focus on the frontal aspect of photographs with regard to the spectator, which had until then been the prerogative of modernist art, and the forme tableau.

And yet, Wall’s writings, in particular Signs of Indifference, give us a more multi-faceted view than the mere counter-positioning of the terms ‘photo’/’picture’, or Fried’s modernist reductivism. Wall takes a leap back to the 1930s - Reculer pour mieux sauter – when artistic photojournalism was first developed. This form of expression, Walls claimed, was a “social institution” that “can be defined most simply as a collaboration between a writer and a photographer,” with the added ingredients of a quest for spontaneity, an ability to capture the fleeting moment , and the capacity to abandon oneself to the flow of events. Wall traces the emergence of photojournalism even further back in time. That is, to Mallarmé and French Symbolism, when poetry was no longer compared to prose but to the way journalists manipulated language. In a history of art perspective, he placed this to the period between Manet’s Execution of Maximilian (1868) and Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

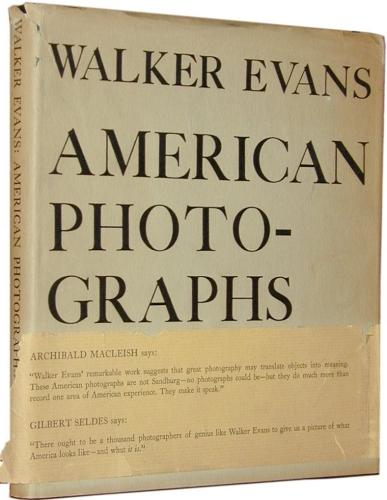

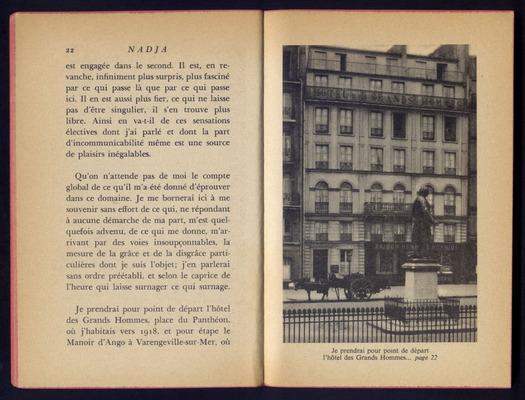

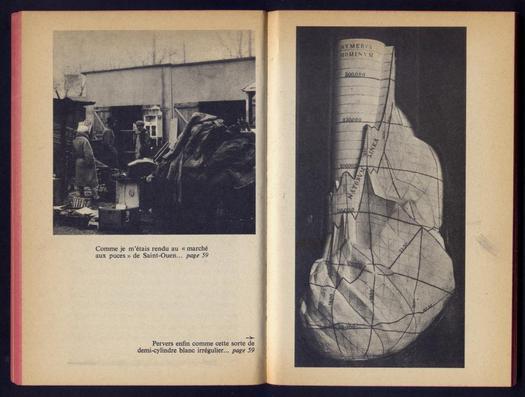

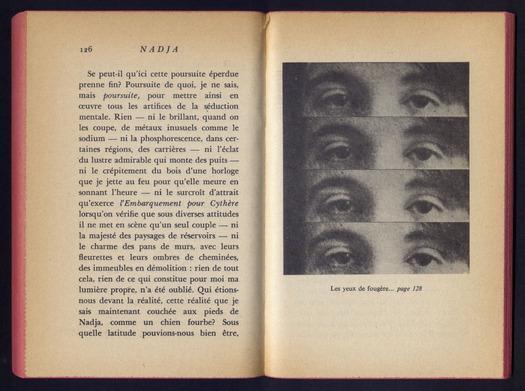

At the end of the 1920s, these ideas converged, when, as Wall put it, the idea took hold that an artwork could be an imitation of photojournalism. At that point, photojournalism started to look like art, and art started to look like photojournalism. Wall cites two essays and a novel as evidence: the essays were The Author as Producer (1934, in Understanding Berthold Brecht, Verso, 1998) by Walter Benjamin and the exhibition catalogue American Photographs (MoMA, 1938) by Walker Evans; the novel was Nadja (1928) by André Breton, with photographs by Jacques-André Boiffard, which Wall considered the first expression of the “concept of photojournalism as a work of art”.

Walker Evans was for Wall a model. Employed as a photographer, he turned freelance and became a photographer/modern artist who bridged the gap between photo-journalism and artistic photojournalism and between working for magazines and experimenting with a personal style. The reason for this important shift , in Wall’s view, was that photojournalism was limited in its scope. Innovation was fueled by the shortcomings of photojournalism rather than by its success. Only by focusing on the limits of journalistic photography, Wall concluded, is artistic journalistic photography possible.

Art/Photography

This is at the root of Wall’s philosophy, which is expressed more fully when he tackled the period between 1955 and 1978. This is the period Wall found most interesting, when photography gained institutional and commercial legitimacy in its own right. They were the years of the neo-avant-garde, activism and experimentalism, conceptual and post-conceptual art, performance and land art. Wall cites in particular: the integration between reportage and performance (Richard Long, Bruce Nauman); the parody of photojournalism in the “mock travelogues” of Robert Smithson (The Crystal Land, The Monuments of Passaic, Incidents of Mirror-Travel in the Yucatan); Dan Graham’s photographic essay Homes for America, 1966; Ed Ruscha’s books between 1963 and 1970; Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter and On Kawara’s interest in photo-journalism, “an attempt to re-create a sort of peinture de la vie moderne”; Marcel Duchamp and other artists who dealt with the esthetic issues of photography without falling into the trap of adopting a facile multi-media hybrid style (which Wall frowned upon); the work of photographer-critics such as Alan Sekula and Victor Burgin, not to mention Bernd and Hilla Becher, Douglas Huebler, Keith Arnatt, John Hilliard, Mel Bochner, Joseph Kosuth, and Art & Language.

Ed Ruscha

What did such wildly different practices have in common? The fact that they resisted the modernist tyranny - despite many differences and distinctions - of the autonomous esthetics of the 1940s and 1950 launched by Michael Fried. In terms of autonomy, photography abandoned the idea of composition, borrowed from the tableaux of classical painting and still operative in the works of Paul Strand, Brassaï, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. As far as authorship was concerned, “skill, craft and imagination” came to be less valuable when “the image-producing capacity of the average citizen was about to take a quantum leap”. That was when, Wall claimed, “amateurism” ceased to be a technical category and revealed itself as a “mobile social category” in which limited skill became an open field of research.

In the modernist perspective adopted by Wall in his history of photography, there were no alternatives: “Autonomous art had reached a state where it appeared that it could only validly be made by means of the strictest imitation of the non-autonomous.” Wall points out the paradoxical nature of this phase. On the one hand, he knew well the classic masters of photo-documentation (Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, August Sander) and artistic photojournalism (Bill Brandt, William Klein, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Weegee). These are the photographers he has studied most deeply and respects the most. On the other hand, however, he seemed unable to avoid preferring artists who parodied photo-documentation and artistic photojournalism . He felt that Evans, Atget, and Strand produced “better” photographs in terms of art, “pure and simple”, than Smithson and Ruscha. The problem was that the concept of “better” was forbidden at the time.

In the section on ‘Amateurization’, Wall is even more explicit. After the 1960s, photography was no longer rated on its artistic value, even though it was deeply rooted in the pictorial tradition of modern art, and developed an esthetic based on a “look of non-art”. The intentions of a photograph were less rated than their automatism. Conceptual photography was seen more as a conceptual use of “readymade” photography.

Wall considered this de-skilling of the photographic medium, this appropriation of amateurism and reduction to the “anesthetic”, an “act of internalization of society’s indifference to the happiness and seriousness of art.” In this view, citing Adorno’s ‘Esthetic Theory’, art was tolerated by society only when it was reduced to “signs of indifference”. The avant-garde shock could only have come about by means of this self-critique – a self-imposed deposition - of the esthetic principles of the artistic medium of photography. For a talented artist with technical skill, it became “subversive” to imitate an unskilled artist. Wall underlined the risk of this operation: the extreme reductivism of amateurism accentuated the similarity between “art and non-art”. This mimesis of the “an-esthetic” risked identifying with “the aggressor” in the case of Warhol, for example. “Photoconceptualism” opened the way to the complete acceptance of photography as art – “autonomous, bourgeois and collectable” – by insisting on the idea that photography was “a privileged means” for denying the idea.

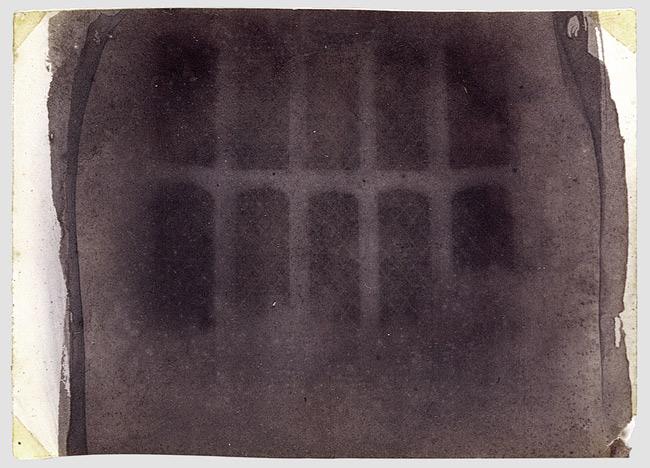

The twofold nature of photography is part of its history. Thierry de Duve observed a curious coincidence. The death of art was prophesied by Hegel in 1839, the same year that William Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre independently made their invention of photography public. Fiat photo et pereat ars. The death of art was accompanied by the birth of a medium that, as Jeff wall reminded us, set in motion the historical process of modernity.

Since 2011

Since 2011