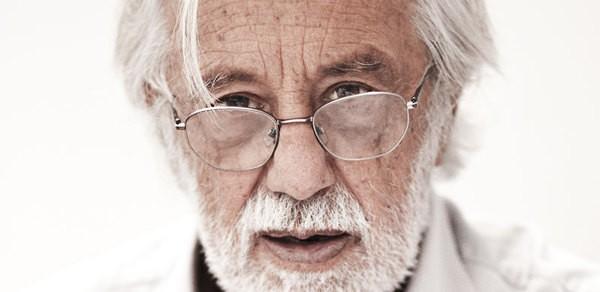

Luca Ronconi, one of Italy’s greatest theater directors, died on February 21, 2015, just before turning 82. His last productions touched on the theme of death, which he probably felt breathing down his neck during his countless sessions on the dialysis machine, during those innumerable hours of immobility. A man who was constantly boiling over with new ideas was forced to face up to the ghosts of his mind, the same ghosts that were represented on stage. Suspended deaths, like in his recent production of ‘Celestina’ that opened with the body of Melibea. Doors on set opened to reveal pulsating worlds of sex and intrigue, then led back into emptiness before returning, at the end of the play, to the lifeless corpse of the young protagonist. Ronconi’s rendering of Spregelburd’s ‘Panic’ comes to mind, as well as his final production, Stefano Massini’s ‘Lehman Trilogy’ performed at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan after his death. In this play, the world of the living - thanks to further doors designed by Marco Rossi, which were more ethereal and minimalist than those in ‘Celestina’ - intermingled with the world of the dead. In the case of the Lehman Brothers saga, people who had no desire to leave this world, relatives and descendants of the tragedy, a trapeze act, balancing precariously on the high wire of the volatile economy.

Ronconi was an inventor of spaces. Spaces to contain words. Spaces to give a dimension to texts. Texts which were destined to be unpicked, analyzed and re-interpreted so that they could be understood. Texts which could even be over-ruled by Ronconi’s actors applying his famous technique. This involved dilating, highlighting, or accentuating certain parts of the text in a continuous quest for the subtext, the life that lives inside the words, the hidden intention of the language, the potential multipliers of meaning or opacity.

In addition to these acting techniques, Ronconi also adopted mechanical devices to further his ends. These include Baroque theater carts, as in his unforgettable ‘Orlando Furioso’ labyrinth, or adaptations of theatrical space, such as his reconstruction of a train station in the ‘Last Days of Humanity’ staged inside the Lingotto, former FIAT car factory. Mirrors were another favorite, mirrors reflecting, for example, a historical street in Ferrara in his ‘Amore allo Specchio’. Or flying machines on stage, creating a sense of vertigo in the audience by means of contemporary physics, such as in the Milanese production of ‘Infinities’. Or again, journeys. Archaic journeys, such as in his 1972 production of ‘Oresteia’ and journeys in the contemporary world of subprime mortgages, as in the ‘Lehman Trilogy’. Or journeys from novels, such as in ‘That Awful Mess on the via Merulana’ , Brothers Karamazov, and Lolita, a production from many years ago on Lake Zurich (Kleist’s Kätchen von Heillbronn, with an oscillating mechanism that accompanied the emotional swings of its protagonists). Other experiments included the use of photography, as in Ibsen’s ‘Wild Duck’; an itinerant production with the Prato Laboratory of ‘The Bacchae’ inside a former orphanage back in the 1970s with an unforgettable solo performance by Marisa Fabbri; another over-ruling of the text in a production of ‘Ithaca’ by Botho Strauss, and a reversal of expectations in Emanuele Trevi’s Cave of the Nymphs, where the entire audience was on stage and the dress circle and balconies completely empty. There are so many productions to his name that one could go on indefinitely. He never stopped experimenting. For him, creating innovative theater was the quintessential cultural challenge.

Calisto (Paolo Pietrobon) e Melibea (Lucrezia Guidone) in Celestina, di Michel Garneau, regia Luca Ronconi

Calisto (Paolo Pietrobon) e Melibea (Lucrezia Guidone) in Celestina, di Michel Garneau, regia Luca Ronconi

Ronconi started out as an actor in 1953. There is a famous photograph of him stabbing Vittorio Gassman during a production of Squarzina’s ‘Tre Quarti di Luna’. He was a symbolic figure from the outset, an intellectual artist who soon went to the other side and began directing other actors. Some say he bent their thespian instincts to his vision; others that he created a dialogue with his actors, and strived to teach them to penetrate the text the same way he did in order to discover surprising and original interpretations. This was his key skill. He forged many brilliant actors through this dialectic exchange, and he urged young actors to rise to his challenges. In his imposing project for the Turin winter Olympics, ‘Domani’, for example, he tested them with ‘Silence of the Communists’, an exchange of letters between the left-wing journalists Vittorio Foà, Miriam Mafai and Alfredo Reichlin on the identity of the left. This piece was influential in the maturing of talents such as Maria Paiato (who worked with the director in his last productions), Luigi Lo Cascio and Fausto Russo Alesi. Teaching was his vocation, and in his famous Santa Cristina summer schools in the Umbrian countryside, Ronconi exchanged views with new generations of directors. In an interview he once rejected the title of ‘Maestro’, justifying this by saying people called him ‘Maestro’ only because he had worked for many years in the Opera, “and everyone is a Maestro there. It is a title I find embarrassing, and I would only use it ironically.”

Orlando Furioso, Spoleto, Chiesa di San Niccolò 1969

Orlando Furioso, Spoleto, Chiesa di San Niccolò 1969

Opera and melodrama were another area of expertise for Ronconi. His stage productions were richly visual, and were generally set in the period the piece was written. Wagner’s Tetralogy, for example, used nineteenth-century costumes and Biedermeier-inspired designs. His production of ‘Nabucco’ in Florence, the critic Gerardo Guccini pointed out, “ interpreted the pretentious, provincial and petty life” of the city.

The critic who followed Ronconi’s career most closely was Franco Quadri. He defended the theater director from his many detractors and wrote a book in 1973 to explain Ronconi’s artistic and intellectual roots. In this book Quadri claimed Ronconi was unwilling by nature to use contemporary texts. One reason he gave was that having started his career in the 1960s, the repertory and the theatrical context was stuck in a series of obsolete clichés. At the time it was imperative to clear the decks of tradition. The bomb that set this trend off was Ronconi’s Orlando Furioso, re-written by Edoardo Sanguinetti (Claudio Longhi, one of Ronconi’s star pupils, wrote a book about the production). The theatrical show invaded the town squares, interwove episodes with carts piled high with sets and actors, forcing the spectators to move from one piazza to another, and create their own performance according to a ritual which felt more like a game. This was one of the very first productions in Italian contemporary theater. It took place in 1969, only two years after the Ivrea conference on New Theater had demanded that theater writers be more scenic. Ronconi went on to invent new mechanisms to re-experience texts, create groups of loyal actors who would assimilate and share his idea that making theater means working together in an ensemble. In the end he had successfully created a utopia, where like-minded people worked to a common end, which was to analyze reality rigorously and then transform it on stage.

Orfeo ed Euridice, Firenze, Teatro Comunale, 1976

After producing plays by the classics – Aristophanes, Aeschylus, O’ Neill, Calderon de la Barca, Shakespeare, Goldoni, Ibsen, Pirandello, Brecht, Kraus, Dostoevskij, Gadda, Nabokov – Ronconi did indeed move on to contemporary authors. These included the physicist John Barrow, the economist Giorgio Ruffolo, Edward Bond, Lagarce, Jeaggy, Spregelburd, and Massini. Ronconi’s curiosity was never satisfied, and his compulsion to experiment brought him to the frayed edges of the present day. He had a unique capacity for experimenting with new production spaces and contexts. He worked with both cooperative acting companies and with big national theaters. Finally He brought unforgettable actors, such as Massimo Foschi, Mariangela Melato, and Marisa Fabbri, to his Rome, Turin, and Milan public theater productions.

Mythology and the economy. Words interpreted spatially, stretched or shrunk according to the acting challenges, space with many different dimensions, with worlds that live together as in ‘Infinities’, or the vertiginously leaning stage floors of ‘Panic’ and ‘Celestina’, with those dead people who return to life in ‘Panic’, ‘Celestina’ and ‘The Lehman Trilogy’. Reality seen as innermost thoughts or memories, such as in Gombrowicz’s ‘Pornography’. Reality which included the inevitable deletions of pain, returning figures, wishes and absences, unstable equilibria in the germination of life, glances beyond the thresholds of the doors on stage, the silence of emptiness to be filled with some other words or phrases which have, in their turn, been picked apart, analyzed and then revealed to the audience.

Farewell, maestro (I’ll keep it lower case so as not to disturb your sensibilities). Italian theater has lost a curious and indomitable inventor, a provocateur of new visions. Italian culture has lost a great intellectual, whose profundity, sensitivity and complexity belong to another era.

Since 2011

Since 2011