In the beginning there were movie theaters, with their giant screens and comfortable armchairs, a darkened room, ice creams served by ushers, and, of course, an audience. There were annoying people coughing, heads too high in front of you, or too low behind you, unwarranted comments during the interval. Most important, back then, the show came to an end. There were double bills, of course, where the first film cost more than the second. But opportunities to see your favorite actor, actress or director’s other films were minimal, unless you were lucky and there was a special, a film festival or, much later, late-night replays on television. The bravest of us tried to solve the problem with the only machine on the market for home viewing: the Super 8 projector. After inflicting those flickering few minutes of family birthdays and christenings on your audience, as a dubious reward you could mount whole film canisters and subject your friends to a fairly traumatic viewing experience. The chances of getting to the end of the film without a) the film splitting, b) the light bulb blowing, c) the light bulb burning the film, d) the sound track being inaudible, were as high as the chances of that favorite actor actually walking into the room.

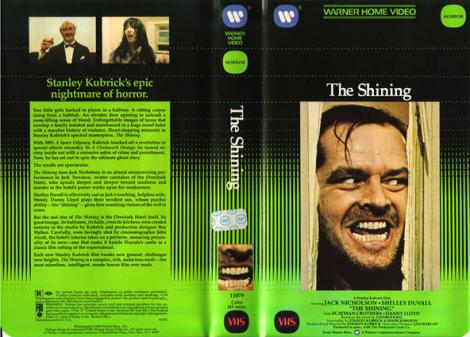

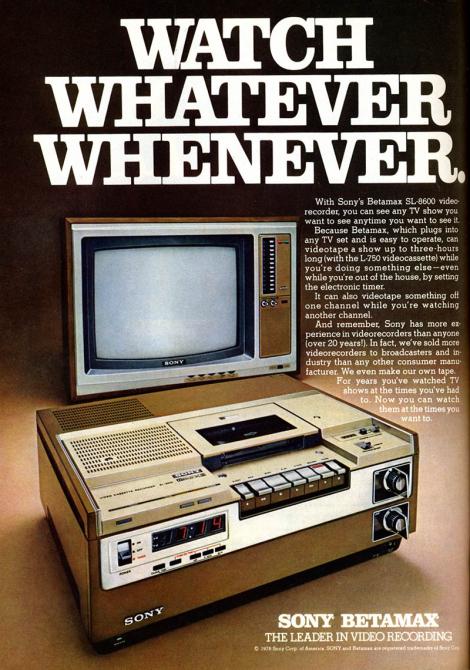

Towards the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, Video Home Systems (VHS) were invented as an antidote for our pent-up frustration. From a conceptual point of view, they were by no means an obvious development. Rather than improving home projectors, which were anyway too expensive for a mass market, the innovation was to create what was to all intents and purposes a portable television broadcasting station. Of course our screens were no longer as big as a bedsheet, and that was our loss. However, being able to find out who the killer was before the film split was an advantage that could not be underestimated. Another key factor was that there was no longer the need to black the room out to watch a movie. VHS came about as a system for watching movies, but it was immediately clear that there was more to it than just that. It was, rather, a domesticated form of television. You could hire a movie and watch it whenever you liked on your TV set, and more and more TV content was transferred and archived on tape for viewing at a later date. Watching the movie ‘live’ was no longer necessary, as the VHS could reproduce the movie at any time. Later, it became possible to record TV content directly. There were two vital functions introduced by Sony with its Betamax SL-800 at the time that seemed unimportant at the time. These were the timer and the pause functions. Although Betamax, the quality alternative to VHS, was never successful, the legacy of these two functions changed people’s viewing habits for good. The timer allowed you to watch a TV program even when you were not home when it was broadcast (effectively, we asked the machine to watch it for us). The pause function allowed us to cut the ads and thus, by contrast, gave us the chance to watch the program with greater concentration. Clean video cassettes, with no interruptions, were the pride of home movie libraries.

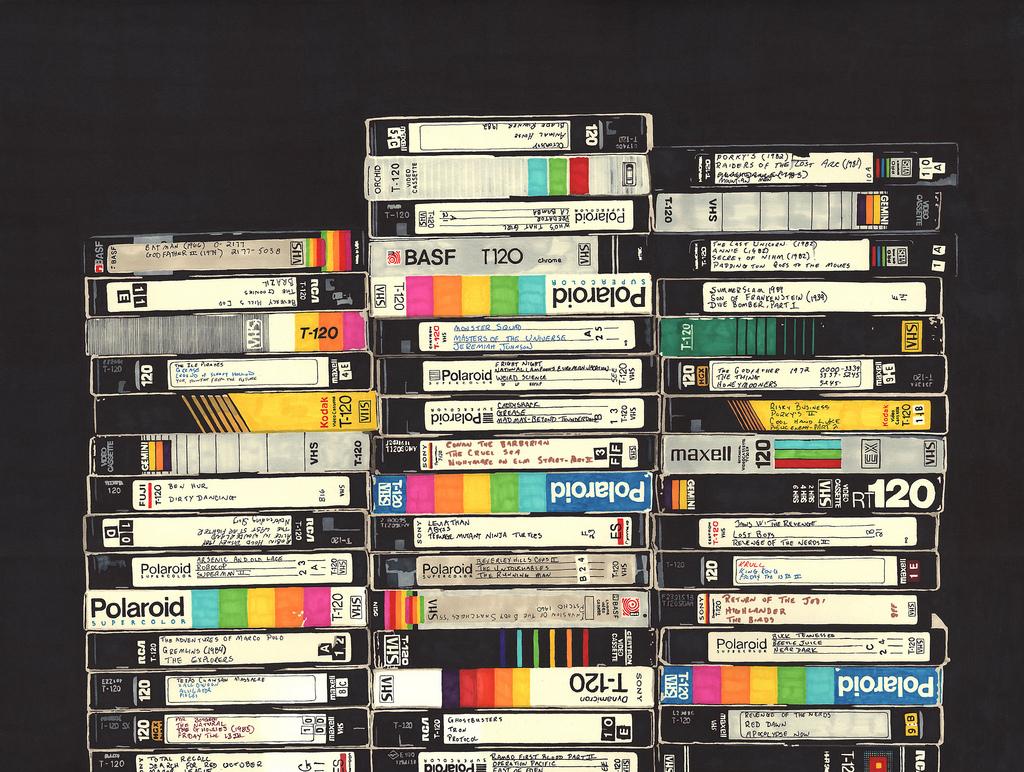

Video Home Systems gave rise to a passion for collecting, in addition to viewing. Collectors treasured their possessions, and took pleasure in classifying and archiving material. And yet it was not the wish to see movies again and again, nor the desire for collections, that awarded VHS such commercial success. It was pornography. At the time, every store selling VHS cassettes had a dark corner, closed off with a discreet curtain, where porn films were out of view but available for people to take home and watch in the intimacy of their own apartments, undisturbed by prying eyes. Finally.

Home videos were also home produced. An important aspect of VHS’s success in the 1980s lay in the fact that family memories were now stored and immortalized in cassettes and no longer in Super 8 reels. In the past, these reels barely lasted two or three minutes, and were without sound. The new heavy home movie cameras more than ten-timed this capacity. And this is when the trouble started. The opportunity for recording hours and hours of film, and the hard work involved in editing and putting together these home movies, made evenings watching (other people’s) vacation films the worst torture imaginable. Hours of instable frames waiting to capture the new baby’s first smile, with dizzyingly close zooms, were enough to trigger violent seasickness or irresistible attacks of narcolepsy. The quirky pleasure of those old Super 8s was instantly replaced, and, worse, the new form of torment lasted much longer.

Speaking of the production side of VHS, what is happening today is very similar. Cameras are everywhere nowadays, in cell phones, in IPads, even in Barbie dolls. But that is not the real issue here. What is important is that all this ‘content’, as it is now called, is managed digitally. It can be used wherever you are, ‘contaminate’ any other device, and be shared with whoever you want. Above all, it can be manipulated in whatever way you want (or don’t want). Cropping and editing is no longer a skill you need years to train for. The devices themselves do all the work and offer user-friendly tools. This is because digitalized images and sounds are data – which is why they are considered ‘content’.

The shift here is in the point of view. For computers they are data, but for us they are films, pictures and webpages. It is through these products that we view the world, and therefore, according to the paradox that is intrinsic in every culture, they give our world a form. The world is the way we think it is not because an obscure psychological mechanism makes us blind to so-called ‘reality’, but because ‘reality’, as an expression, can only exist in relation to its contents. A culture provides a form both for the contents it articulates and for the expressions it uses to describe them. A film clip is never just a memory. It is the way we decide to remember an event. Looking at the world through the lens of a movie camera inevitably transforms the way we experience it; it builds up a point of view in the deepest sense of the term. That is, it builds the premise for the way we conceptualize what is around us and how we experience it. It is in this sense that film is one of the key languages of contemporary life. More than photography, which has also experienced a boom owing to digital devices (with reduced prices and increased quality). More than words, which are now back with a vengeance with emails and texting, after the dark ages of the telephone, despite predictions that the written word would soon die an untimely death.

Home movies also challenge our ideas of quality, which, with the latest technology, has become ever more crucial. A new upgrade has hit the mass market recently, bringing about a quantum leap in high fidelity. High Definition (HD) and Super Audio Compact Disc (SACD) has created a format where listening to music, for example, recreates real life experience. In the space of a few years we have replaced our old cathode ray tube TV sets, and our DVD players (which in their turn substituted VHS players), with Blue Ray and High Definition LCD screens, without for one minute thinking about the cost of what we are doing. Why have we collectively abandoned our passion for collecting material for our Hi-Fi systems that dominated the 1970s and 1980s, in a quest for visual perfection that nobody really felt was important until the desire was induced?

It is not so much a matter of finding a definitive answer to this question, as of posing the question properly. The main issue is not that the passion for visual definition has waxed, while the pleasure in high fidelity sound has waned. It is rather that the two trends have clashed and will continue to do so, with dubious results. On the one hand, Mp3 audio compression has inevitably compromised quality, while, on the other, smaller and smaller video cameras have adopted increasingly lower-resolution images. We all demand the highest performance from technology, but at the same time we are willing to accept out-of-focus, pixelated images and are getting used to the kind of low-res home movie images spectators send into news channels when they have witnessed untoward events. In the meantime, the availability of ‘Surround Sound’ systems has transferred the question of audio quality to the home movie domain. This has led to new problems and new esthetic criteria, such as the phenomenon of sub-woofers pumping up the bass line (which hi-fi fanatics abhor, of course).

In conclusion, a recent innovation in the experience of watching movies at home (not the most recent in technological terms) has been the popularity of home projectors. When film cartridges gave way to cathode ray tubes, a whole set of practices were done away with. Most importantly, the fact that the room had to be darkened, which made it impossible (and unthinkable) to do anything else. There was also the assumption that the viewing would take place in the evening, as closing shutters or curtains during the day was never enough to create a total black-out. The return of projectors has brought back some of these rituals. A sheet, or a blank wall, a dark room, light that is absorbed by the screen rather than emanated by it. There is even a return to Saturday night film nights, with high definition sound being reproduced by the new generation of amplifiers.

The conditions for certifying the death of movie theaters (an announcement that has been made repeatedly) are all in place. Even the recent re-incarnation of 3-D (remember the blue and red glasses?) was immediately absorbed by the home movie theater market. If people continue to go to movie theaters it is not for their quality, nor for 3-D productions that have increasingly been relegated to blockbuster films with high-speed action and special effects (hopes that pornography would follow the same trend have been dashed), nor for the earthquake-inducing soundtrack. The challenge of keeping movie theaters alive no longer lies in the technology. It lies, rather, in the nature of the experience of ‘going to the movies’. Sharing the experience with others, laughing at the comments of viewers in the row behind you, or listening to their observations, and perhaps learning something from them, munching popcorn or chewing sweets with friends. All these things contribute to the experience, but the most important, perhaps, is the fact that you cannot stop the film. You cannot rewind. You know that if you’ve missed a detail you’ve missed it. Joint participation (not just ‘sharing’, which computers do so well), and unrepeatability are the two most important bulwarks against the digital revolution.

Since 2011

Since 2011