After the terrorist attack on the Parisian satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo, some commentators wondered what the consequences of a reaction calling for greater security would be for European legislation. The almost hysterical use of the inclusive “we” in the slogans following the attack (Nous sommes Charlie) provide a linguistic clue to the identity politics in play, just as the 9/11 attacks fueled the rhetoric of a “clash of civilizations”. The reaction to both has been a justification for police interventions on an international scale and so-called ‘surgical’ warfare.

The Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, in an interview in La Repubblica (Jan 15, 2015), invited readers to “stay lucid” and not repeat the mistakes of the past. “The overlapping of the concepts of terrorism and warfare after 9/11 led Bush to wage a war […] that cost tens of thousands of lives. Without that war, the tragic attack France is now reeling from may never have taken place.” Agamben foresaw a slippery slope towards “what politologists call a ‘Security State’, that is a state where a true political presence simply cannot survive.”

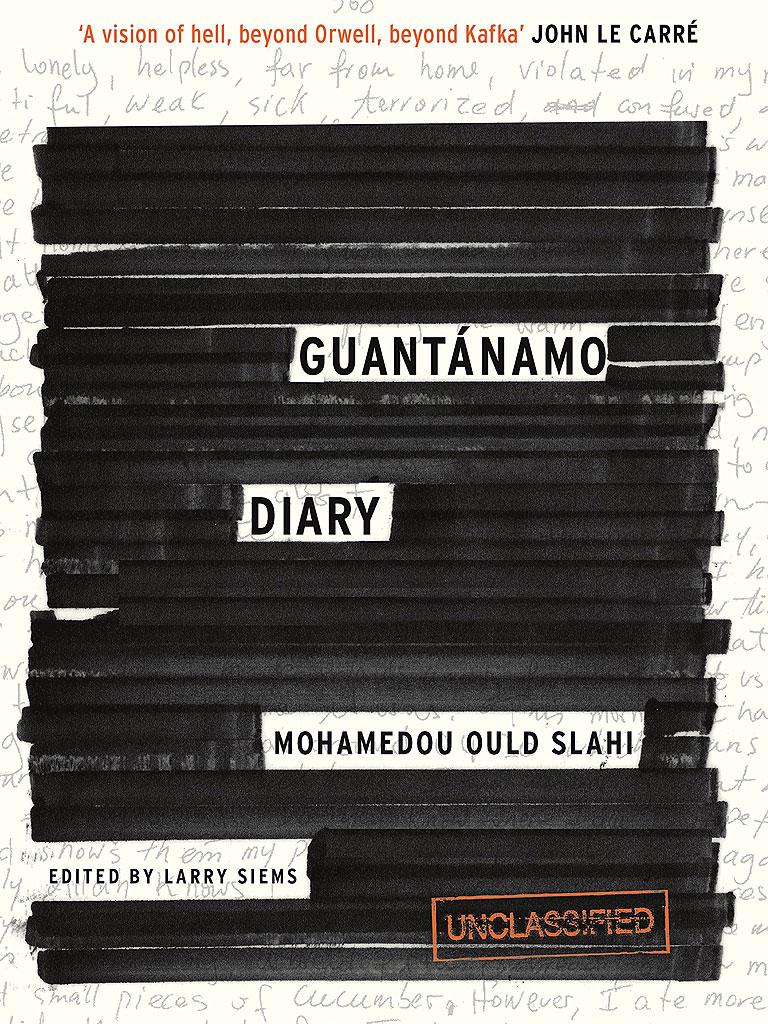

The book Guantánamo Diary was published in January 2015 in the US (Little, Brown and Company) and twenty other countries. The nearly 500-page manuscript written by Mohamedou Slahi, imprisoned at the detention camp at Guantánamo Bay since 2002 without a specific charge, edited and with an introduction by Larry Siems, is a real eye opener in this regard. The magazine Slate published advance extracts in 2013, and The Guardian has followed the project closely from its inception.

Slahi was remanded on suspicion of having participated in the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers in New York. Born in Mauritania in 1970, he studied in Germany, and then joined the ranks of the Islamic Resistance Mujahidin movement, openly fighting in Afghanistan between 1991 and 1992 when this was not only not frowned upon but actively encouraged. He was trained by the US Army which at the time supported Islamic combatants fighting the occupying forces of the Soviet Union. Slahi grew disillusioned with Al Qaeda when vying factions started in-fighting after the fall of the Communists, and returned to Germany to complete his engineering course. He lived and worked in Germany and Canada until 2000, when he went back to his home town, Nouakchott, to work as an engineer.

Anti-terrorism intelligence considered Slahi an Al Qaeda associate, and a participant in terrorist campaigns on US soil. After 9/11, Slahi presented himself voluntarily to the Mauritanian police for questioning, and as a result of this he was ‘rendered’ to black sites abroad. Slahi has been in detention ever since. As a prime suspect in the 9/11 attacks, he was transported first to a special detention center in Amman, Jordan, then to Bagram prison in Afghanistan, and finally to Guantànamo, in a downwards spiral of human rights violations, mistreatment, and torture.

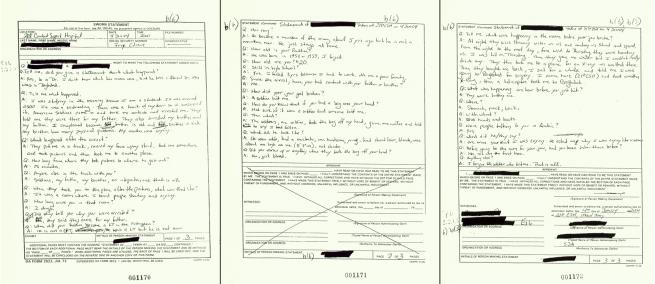

Slahi was harshly interrogated, subjected to sensory deprivation, put in isolation, repeatedly beaten, tied up in torturous positions and humiliated sexually. He was forced to listen to music at high volume, blinded by bright lights, and dunked in icy water. He was "force-fed seawater, sexually molested, subjected to a mock execution and repeatedly beaten, kicked and smashed across the face, all spiced with threats that his mother will be brought to Guantánamo and gang-raped." He was transported overseas in high-speed boats under extreme conditions while facing constant death threats. His diary was first requisitioned and classified, and when the authorities handed it back to the parties who were following the case with great interest, the de-classified document was filled with blacked-out ommissis.

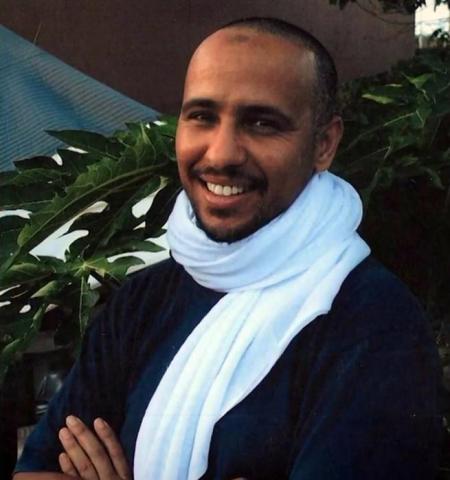

Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Slahi started writing the diary in 2005 while in a segregated cell at Camp Echo. The thousands of lines classified by the US government (illustrated on the cover of the US edition) are a continual visual reminder of the conditions under which Slahi was writing. Publication of ‘Guantànamo Diary’ required years and years of legal wrangling. The Slahi case is a symbol for all those who believe in justice and civil liberties, and dissemination of his work is a crucial stepping stone in the battle against the detention center and the mistreatment of its prisoners.

The Diary highlights many issues. The first, of course, is the inhumane treatment of all prisoners and the real value of interrogation procedures – issues that Cesare Beccaria dealt with 250 years ago. Slahi writes that in order to persuade his tormentors to stop he gave false confessions. Torture, in his view, can only produce lies. Initially, he states, he tried to defend himself, but “post-torture” he said yes to “whatever accusation was made” in order to “get the monkeys off my back”.

A key issue is the lack of evidence justifying his detention, which was preventive and punitive at the same time. After a legally approved protocol, signed off at the highest level (‘Additional Interrogation Techniques’ bore the signature of then Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld) the torture worsened. Slahi was subjected to endless interrogations, forced periods with no sleep, humiliation and gratuitous violence. In 2010, a sentence found the accused probably had “no knowledge of the 9/11 attacks”.

The Diary provides a detailed chronology of Slahi’s detention and, as the story unfolds, the progressive legal actions undertaken to no avail. The Department of Defense holds Slahi under lock and key to this day, in the same cell where much of his story takes place. Larry Siems informs readers that his detention was based on legal foundations allowed under warfare, the 2001 AUMF law (‘Authorization for the Use of Military Force’).

Siems is the human rights lawyer and activist who edited the de-classified Dairy. Author of The Torture Report: What the Documents Say About America’s Post-9/11 Torture Program (O/R Books, 2011), Siems guarantees the truthfulness of Slahi’s eye-witness account. After reading everything there is to read on the Slahi case, Siems cannot understand why Slahi is still “locked up down there”. He invites readers to form an in-depth understanding of the reasons for this legal and humanitarian nightmare.

Jenny Holzer, Jaw Broken, 2006, © 2009 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In the post-9/11 debate, there are many who still justify the legalization of torture on the basis that it can save other people from future attacks. Obama’s electoral pledge to dismantle Guantànamo has not yet been realized, even in his second term with new foreign secretary.

After Judge James Robertson at the US District Court – the only judge ever to have examined Slahi’s case folder – ordered his release in 2010, the New York Daily News and other conservatives decried the “outrageous decision to free a 9/11 criminal” The Obama administration also appealed.

The film directors, Winterbottom and Whitecross, followed the same lines when they made the documentary film, ‘The Road to Guantànamo’ in 2006. This was based on the similar experiences of Ruhal Ahmed, Asif Iqbal and Shafiq Rasul, three young British Muslims captured in Afghanistan and accused of being Al Qaeda fighters.

‘Guantànamo Diary’ provides a first person eye-witness account of prison life. Slahi’s attempt to communicate with the outside world, and validate his experience of the hidden world behind the public face of the Guantànamo detention center, without “exaggerating or understating”, is written in what is his fourth language. What emerges, is a universe of brutality and degradation, an incomprehensible mechanism that crushes the young Muslim in its vise-hold. And yet Slahi never loses sight of his humanity or sanity, despite the extreme cruelty of his position.

Slahi speaks of hallucinations and crystal clear voices in his head. He relates how he would hear his family going about their business and was unable to join in. He would hear the Koran being read out in a heavenly voice. He would hear music from his homeland. Later, he recounts, the guards used his hallucinations as inspiration, and spoke to him through the pipes, pretending to be these people, encouraging him to rebel and plan his escape. He writes that he didn’t let them deceive him, but played their game.

Exchanges with guards are recorded in detail in the ‘Diary’. They were friendly, and discussed the fact that “human beings hate torturing people, and the Americans are no different.” Many soldiers, they claimed, were reluctant and were happy when they were told to stop. In general, Slahi concludes, human beings only resort to torture when they have sunk into “chaos and confusion”.

‘Guantànamo Diary’ also appeals to the world outside the prison. He writes that he has tried to be as fair as possible “to the American government, to my brothers, and to myself”. If the Americans are willing to “defend the values they believe in”, he exhorts, “I expect public opinion to put pressure on the government” and open an inquiry into torture and war crimes. “Many of my brothers here are losing their minds” owing to prison conditions, Slahi denounces, especially the younger ones. “Many of my brothers are on hunger strike”, he continues, asserting that they will continue to refuse food, whatever happens.

Manifestazione Amnesty International, 11 gennaio 2013

notorious images of Abu Ghraib prison come to mind. It is hard to forget the short-circuit between the severity of the violence inflicted on prisoners there and its representation and consumption in the international arena. The message was clear. As in many other situations where ‘normal’ people commit unspeakable violence, it is a proven fact that individuals can be transformed by their context. Stanley Milgram and Philip Zimbardo’s research in the 1960s and 70s proved that social pressure and obedience to authority can extinguish an individual’s sense of responsibility and release codes of violent behavior that are usually held at bay. The two social scientists proved not so much that “evil” is recurrent in human nature (that old chestnut again), but that in certain circumstances ordinary men and women are willing to tolerate and commit acts they would ‘normally’ never dream of. What kind of circumstances were they talking about? Thirty years after the famous Stanford University experiment, Zimbardo claimed that during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the issue was not so much the soldiers’ “nature” as the fact that they belonged to an organized army, sent to war for “a just cause” against terrorists.

Guantànamo is a similar circumstance, but it de-humanizes individuals in a different way. Abnormal behavior is released by a legally-recognized suspension of human rights and by a stay on human dignity in the name of security. This is compounded by a socially-invoked ‘emergency’ that is accepted as such by citizens in a liberal democracy. The special laws not only give rise to, but also justify, the existence of an ethically unacceptable system which is not the product of the random whims of a sadist, but which liberates sadistic impulses.

Of course, it can be argued that American society has laws and institutions in place that are valid antidotes. These include freedom of speech, the possibility of reviewing the legal process, a pool of federally mandated defense lawyers, activists, the media, and public opinion – which is the reason we are talking about this in the first place. However, these antidotes are not sufficient. Ordinary rule of law and emergency laws are two different spheres. They are contiguous but they do not overlap, they are selective and they exclude each other. Their existence side by side does not mean they communicate with each other.

1/11/2014

In the media world we all live in, where readers and viewers still demand reflection on the past and the present, ‘Guantànamo Diary’ hit the bookstores and public opinion a few days before January 27th, the day of remembrance for victims of the Holocaust. I am not suggesting implausible comparisons here. Nor am I claiming there is an absolute, metaphysical ‘evil’ for which any number of episodes throughout history would form the underlying substance. What I am saying is that we should take that event as our starting point and ask ourselves what this means in terms of collective memory, with the extreme consequence of censuring the legal, ethical and pedagogical framework since World War II. Our collective memory, our civilization, our reflection.

Concentration camps required institutions. Research has shown that abuses of the law and massacres of civil populations can be perpetrated by representatives of a State, in agreement with the laws that a legitimate and recognized authority emanates under exceptional circumstances. Other research has focused on the subjects. Raul Hilberg found a triangular system in place in Auschwitz, made up of victims, perpetrators and spectators, and suggested that it would be useful to analyze the various contexts in which these three forces interplay. It is no coincidence that Milgram conducted the research cited after witnessing the Adolf Eichmann trial in 1961.

Primo Levi, the exceptional writer, profound thinker, and eye-witness of atrocities in the camps, claimed that the dimensions of the phenomenon of Nazism were unprecedented, and outlined the similarities and differences with other regimes such as Italian Fascism, Soviet concentration camps, the Greek dictators and the Pinochet regime in Chile. On the basis of his idea that Nazi totalitarianism – with extreme, homicidal consequences - laid bare the inherent contradictions in the development of modern society, Primo Levi observed the hidden aspects of democratic societies. In his introduction to the school edition of his ‘If This is a Man’, he wrote:

“I don’t think there have been gas chambers or incineration ovens in any other part of the world, but it is impossible to read without concern that the Greek Colonels or the Chilean Generals built concentration camps, in Yaros and in Dawson. Today there are prisons, youth offender reformatories, and hospitals in almost every country, where, just as in Auschwitz, human beings often lose their name or their face, their dignity and their hope. The experience of the past, owing to its very crudity, has turned us into accusers rather than judges. Seeing the seeds of fascism taking root in the same countries (not in the same people) to which the world owes the defeat of Nazi Fascism gives me pause and fills me with horror.”

Levi’s account of life in the camp is a reagent to analogies with the present day. He cites previous experiences that may have contributed to the phenomenon. These contributing factors, in Levi’s view, include limitations of freedom, bureaucratic and legal violence, systematic threat, conformism, racism, and xenophobia. Meanwhile, post-totalitarian sensibilities have been attenuated, the potential for political evil has expanded, memory has been institutionalized (not without unexpected corollaries such as the paradoxical competition among victims for recognition of their suffering).

The story of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, held at GTNMO, prison number ISN 760, is part of this present day context. It is very different - in terms of events, subjects, numbers, opponent sides, and narrative - from 70 years ago. What is similar, however, is the mechanism for expropriating rights that lies at the heart of the very democratic rule of law that was created from the ashes of the old world order.

Knowing about the human rights violations of the past helps us recognize those taking place today. It raises our awareness and shows us how to recognize the signs of the conditions that lead to these violations. It educates us to oppose them. In order to avoid our relationship with our past becoming merely ceremonial and rhetorical, with no impact on the present day, it is fitting to add Guantànamo to all the other experiences that build up our paradigm for our aversion for the ‘other’ and for our inevitable trend towards authoritarianism.

Since 2011

Since 2011