Maurits Cornelis Escher visited Italy for the first time in 1922. The master of perspective and transformation, whose trade mark was to create deceptive images by making his subjects one with their backgrounds, arrived from his home town of Haarlem with two friends on the traditional Grand Tour. The three young artists, Escher, Jan van der Does de Willebois and Bas Kist, were all pupils at the well-established School of Architecture and Decorative Arts, where they were apprenticed under Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita, who introduced them to the art of woodcutting. The itinerary of their Tour was linked mainly to the ‘old masters’ who were so popular back home. Their work served as a model for the remarkable paintings of Jan Verkade (the subject of a magnificent portrait by Giovanni Papini), who, in his turn, had studied with Gauguin before taking orders and retiring to a monastery. The Tour left Escher with an indelible impression of Siena, and San Gimignano in particular. His prints of these cityscapes show the extent to which the artist was engaged by the unexpected verticality of the architecture and the city’s surprising chiaroscuro, both of which represented such a marked contrast to the minimal variations in the horizontal uniformity of the Dutch sea and landscape.

Although he travelled widely and intensely up and down the country, with an increasing preference for the South (he spent extended periods in the Abruzzi, Campania and Calabria regions) Escher spent twelve years in Siena and only left in 1935 because the Fascist regime became unacceptable to him. He lived in a Pension at via Sallustio Bandini 19 where his landlady, Giuseppa Alessandri, became a close friend. There is no plaque on the street today, but we know that this is where Escher met the love of his life, the Swiss daughter of an industrialist, Jetta Umiker, whom he married in the Viareggio town hall in 1923.

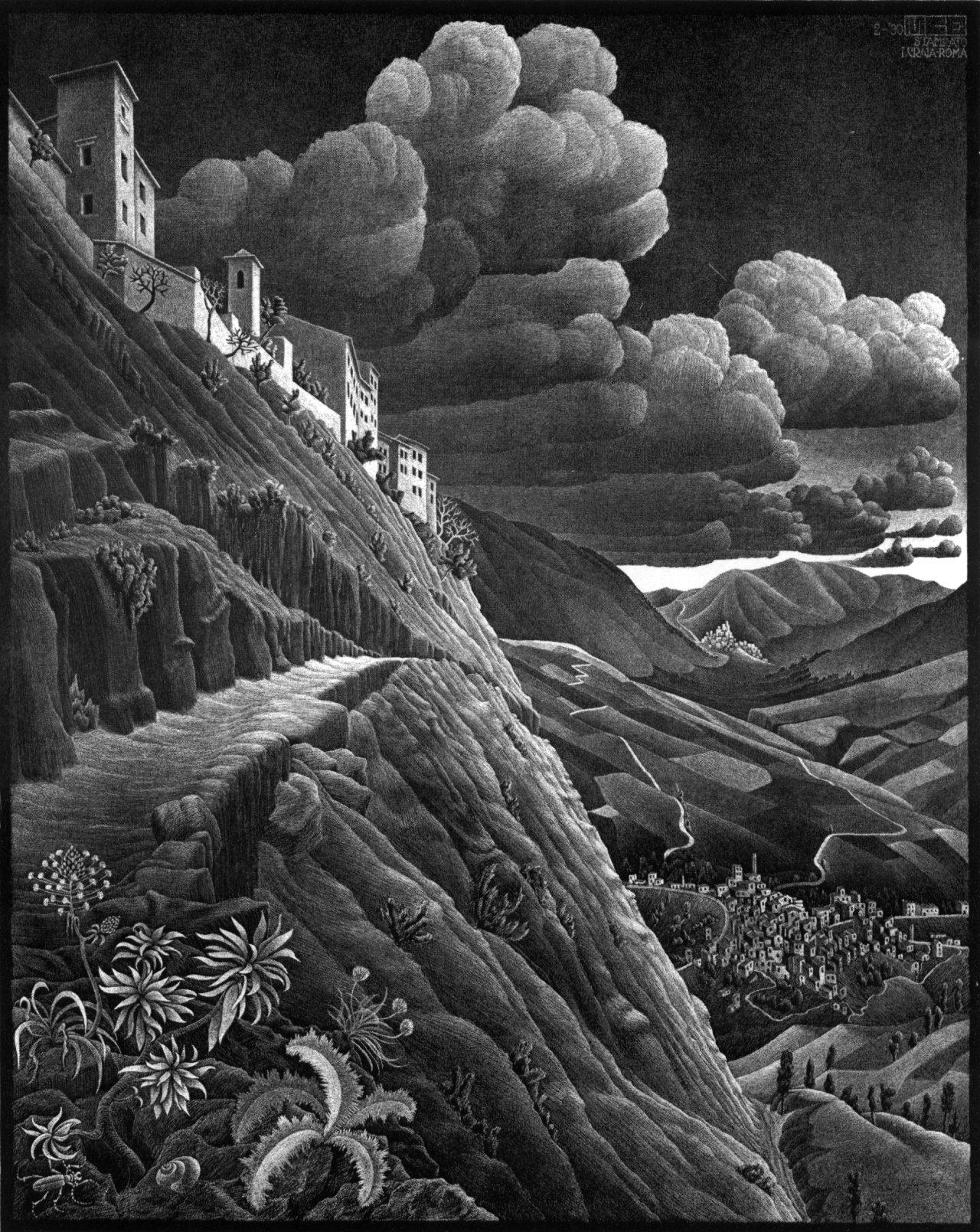

Escher held his first exhibition of landscapes – his exclusive interest at the time - in Siena, which he called ‘Black and White’. His poster design advertising the show reproduced the city stem. There are many etchings portraying the roves of Siena and the mysterious atmosphere of balmy evenings in the narrow streets of the city which bear witness to this period of apprenticeship. Escher’s cityscapes of San Gimignano are equally striking. In one print in particular, he pays homage to the style of the Japanese masters, his woodcuts seemingly inspired by Hokusai. The city of towers is depicted at the top of a hill streaked with engraved wavy lines, a tree bent by the wind standing in the foreground. The Italian artists who inspired Escher the most in this period were Duccio da Buoninsegna, Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the surprising Sano Di Pietro. This lesser-known artist seduced Escher with the metaphysical compartments in his representations, such as, for example, in the magnificent Sermons of St Bernardino preserved in the Museo dell’Opera in the Cathedral of Siena, which have the same foreboding as some of De Chirico’s paintings depicting Italian Piazzas.

Giandomenico Semeraro published Escher’s diary from that period in the volume Bianco e nero. Maurits Cornelis Escher a Siena (Pacini Fazzi, 1996). The entries bear witness to the intense visual stimulation the artist received and how this inspired his work. The page corresponding to May 7, 1922, is a leap into the artistic past: “This morning I followed a lively procession, a band of musicians followed by youths in medieval costume. Each one of them carried a standard, with colors matching their clothes. This multicolored and joyful parade was on its way to a little church in via Romana, near the San Galgano gate of the city. […] I then went on to visit the church of Santa Maria dei Servi, full of amazingly beautiful paintings: a virgin by the Florentine Coppo di Marcovaldo, with strong Byzantine influences, and a Massacre of the Innocents by Matteo di Giovanni, which bears a close resemblance to his altarpiece in the Sant’Agostino church, but which was painted nine years later. There is also a superb Madonna and Child by Lippo Memmi, a small fourteenth century piece depicting a highly ‘naif’ Adoration of the Magi, with two magnificent birds in the foreground.”

Escher’s Flemish-Dutch taste for detail is in his DNA and represents a point of reference in his artistic career. On leaving Italy, Escher returned north, first to Switzerland, then to Belgium and, finally, settled in the city of Baarn in Holland, where the Escher Foundation was later established. Escher wrote that he had always had to invent his own imaginary world as the Dutch landscapes surrounding him did not have the same seductive effect on him as the Italian ones. The mysterious inhabitants of his later etchings are often wearing medieval costumes. It has been written that Escher was inspired by the ancient costumes of the Sienese Palio, using them to dress the figures of his imagination. The style that made Escher famous the world over - etchings which are also mathematical poems - was the result of his reflections on the relationship between nature and nurture, and between the natural and man-made environment, in and around Siena. His incredibly modern vision was born in an incredibly ancient city. In light of the computer graphics available today, this vision is more striking than ever.

Luca Scarlini has written a short theatrical piece about Escher entitled ‘A Modern Vision of Antiquity’ which was performed in San Gimignano in the summer of 2014 with the theatrical company Giardino Chiuso, as part of the festival Orizzonti Verticali (Horizontal Verticals). The work is currently being staged with sets designed by Andrea Montagnini. The Escher exhibition curated by Marco Bussagli, with 150 pieces, was held at the Bramante Cloister gallery from September 20 to February 22, 2015).

Since 2011

Since 2011