Archive

One thousand four hundred sheets of Bristol paper covered in miniature, cautious, cadenced, rounded script. The hand writing continues even when there is not enough surface to contain everything that is needed to be said; the lines get thinner and thinner and increasingly close together, like the jets of smoke acrobatic pilots draw in the sky. There are minimal variations in the script, even though the works span a period of forty years. I’m curious to decipher the words, and go close up to read them. It takes me a while to realize that they are a series of citations since they are not protected by quotation marks. These long passages are free of their source, ready to be re-used, re-appropriated, transformed by the author. A dètournement of this type, in the days of digital cut and paste, feels awfully archeological and terribly wasteful.

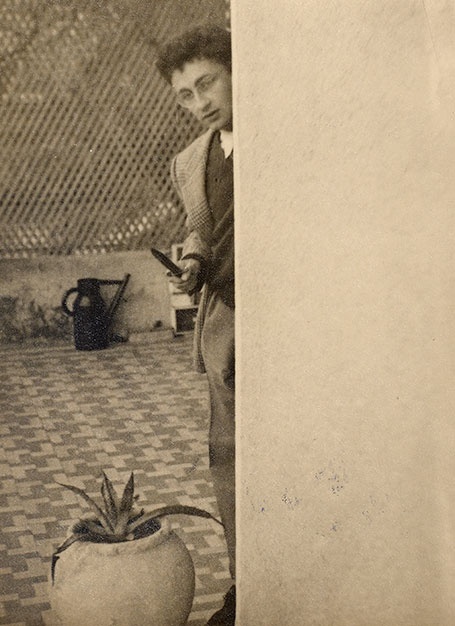

Debord in Villa Meteko, Cannes, before 1950

A wide selection of this archive is on show in this exhibition of Guy Debord’s work for the first time. The exhibition at the Bibliothèque National in Paris, ‘Un art de la guerre’, runs until July 13, 2015. The calligraphic pieces are hung on high transparent, spiraling walls: a maelstrom of ink. Debord was always careful not to underline or annotate the books he read. He transcribed the texts that struck him in particular into various notebooks, which he labelled: Poetry, etc., Machiavelli and Shakespeare, Hegel, History, Philosophy and Sociology, Marxism, Strategy and Military History. The pages of these notebooks are not simply a cabinet de lecture, nor a mere documentary section of the exhibition, like those accessories that fill the blind rooms at the margins of exhibitions to be glanced at if you have enough residual time and energy. This exhibition space - from which the other separate sections of the show, designed by Philippe Sollers as a “travelling library”, radiate - is the engine room. It is almost a journey into Debord’s brain.

Debord collage in honour of Asger Jorn, 1962

With this mental map of the archive in mind, the curators, Laurence Le Bras and Emanuel Guy seem to suggest, we can grasp what the Situationist movement was, how it was propagated, where it failed and what heritage it left behind. What is on show is the writing. Forewarned is forearmed. A visitor to the exhibition Un art de la guerre is required to become a patient, and at times frustrated, reader. It is, after all, housed in the National Library, which bought the Debord archive just as it was ready to be shipped off to Yale. There is more. Let us not forget that, despite its international echo, the history of the Situationist International is limited to the first six arondissements in Paris: café Moineau in Rue du Four where they met from 1952, the Marais, the Luxembourg gardens. The Situationists hung out in areas of Paris where nowadays there are more real estate agencies than artists. It was the last time an artistic avant-garde movement was formed and grew in the heart of a city – exactly where the student revolt of 1968 took place with its barricades in rue Guy Lussac.

Cultural coup

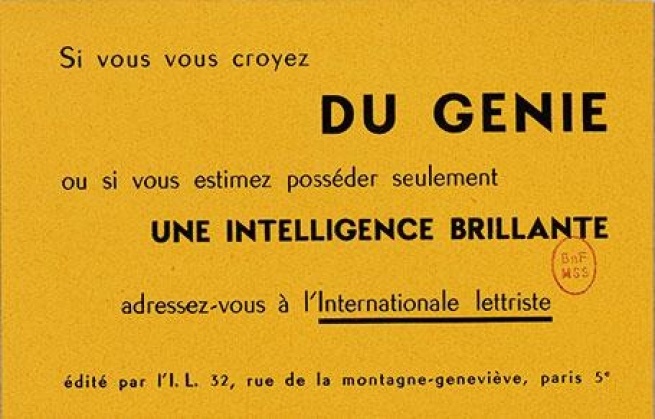

To the eyes of a patient reader of Un art de la guerre, writing was clearly always a vocation for Debord. His school reports are given as evidence for this. At the Lycée Carnot in Cannes, which he attended from 1948-1951, he was awarded the comment “très bon élève” in Italian, “pourrait faire mieux” in German, and in French Composition, “capable de toutes les fantasies”, which is the best possible description of the adventure of the Situationists. The reviews he founded follow: the “Internationale lettriste” (4 issues in 1952-54), “Potlach” (29 issues in 1954-57), “Internationale Situationniste” (42 issues in 1958-59. The original manuscript of De la societé du spettacle (1967) is also exhibited, divided into three little notebooks. According to the French Trotskyist, Jean-Michel Mension, during the thirteen months he was editing this review he stopped drinking, which was an exceptional event. In fact, the activities and ideas of the Situationists were unthinkable without a fair dose of drunkenness. The exhibition also features close relations of writing – voice and music. Debord thought of songs as weapons of propaganda. He wrote Chansons de barricades a Paris in 1968, two songs in 1974 entitled Pour en finir avec le travail and Chansons du prolétariat révolutionnaire, and, as late as 1980, a song defending Spanish anarchists in prison for supporting workers on strike.

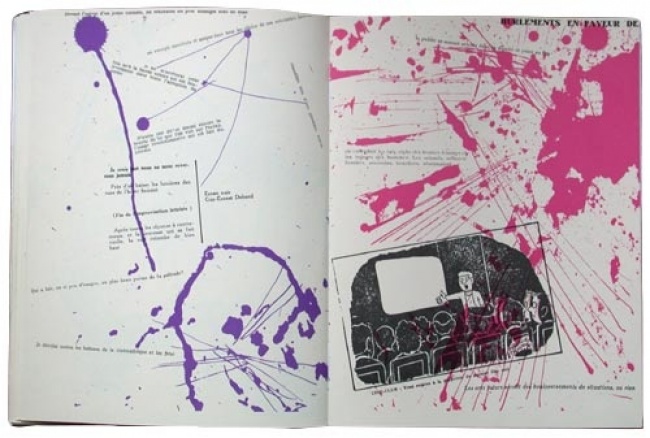

Debord's Mémoires

The frustrated reader will be sure to notice that everyone has his or her own Situationism. Mine, for example, passes through pictures rather than through words. The movement belongs to the Carsic river of the twentieth century, in whose currents you can find Dada avant-garde and punk, as Greil Marcus so brilliantly argues in Lipstick Traces, A Secret History of the 20th Century (Harvard, 1990).

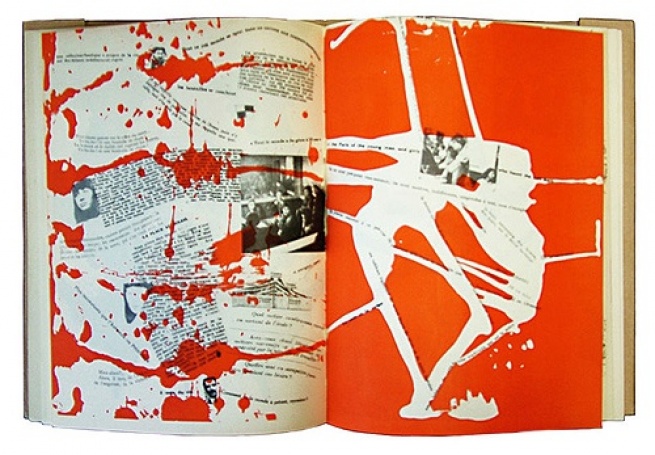

Debord's Mémoires

At the time of the Situationists, dividing pictures from writing may have been a problem. However since the 1980s the visual sphere has, in my view, undergone a recovery. Debord did not take part in the first exhibition on the Situationist International in 1989, despite his bad habit of responding to everyone’s invitations indiscriminately. In 1991 the uncut version of his film was presented at the Venice biennale. In 1997, three years after Debord committed suicide, the Art Historian T.J. Clark and Debord’s English translator, Donald Nicholson-Smith, denounced the attempts of gallerists and critics to “imprison Debord’s negativity in an ivory tower.” ('Why Art Can’t Kill the Situationist International’, 1957-1972) - In Girum Imus Nocte Et Consumimur Igni at the Tinguely Museum, Basel, and in Utrecht in 2007.

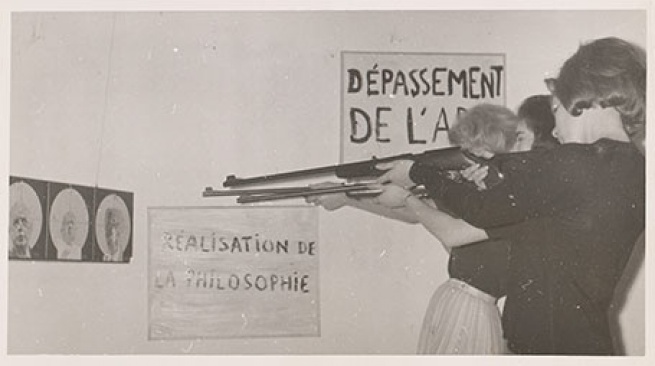

Destruktion RSG-6, Galerie EXI, Odense, June 1963

This visual turn appears to contradict Debord’s intentions. After the Goteborg conference in August 1961, Debord felt the need to give the objectives of his movement a more political slant. He wanted a cultural putsch. The spectacle of rejection gave way to a more radical rejection of spectacle. It became inacceptable to attempt to transform the destruction of spectacle into a work of art.

Directive

This phase coincided with a moment of increased rigidity in the movement, and a more hierarchical structure. There were approximately seventy Situationists, but only fifteen of them were allowed to take part in the meetings. The group was informal, but joining meant leaving every other affiliation, as if the group were a sect. It was only in 1969 that national sections were tolerated. The history of the movement is a series of expulsions and dramatic break ups with precious allies. These included a split with the Letterists regarding the Chaplin affair; with André Breton, when thousands of people received a false invitation to his 60th birthday party to be held in the Lutétia Hotel; with the Maoists, from Sollers, whom Debord refused to meet, to Godard (“le plus con des Suisses prochinois”) and Sartre, “Charogne avancé”; and finally with Henri Lefebvre, accused of copying Debord’s idea that all revolutions, starting with those in the City Council of Paris, should also be festive parties.

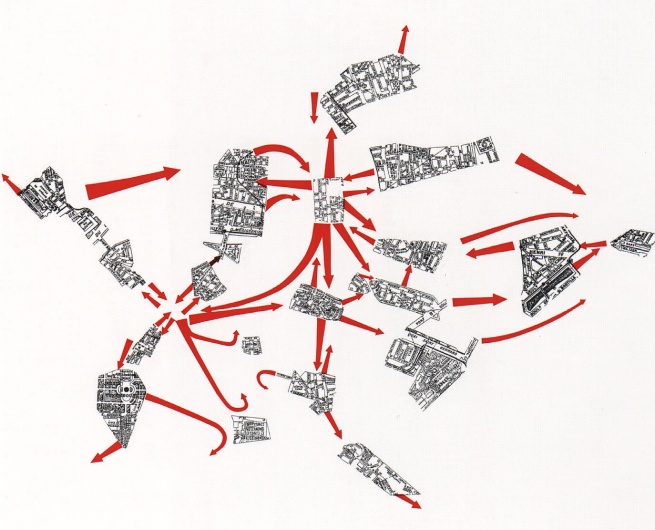

Naked City, 1957

As in group photos in Stalin’s day, Debord whitewashed each of his companions one by one. The strategy was incomprehensible, especially given the numerous conceptual borrowings without which the Situationist International would simply not exist. These include the critique of daily life and the romantic revolutionary spirit of Lefebvre; the Cobra group’s Psycho-geography (Constant and Jorn); the Dadaist and Surrealist diversion; the estrangement from Baudelaire, and many more besides. How these purges contributed to the rejection of spectacle is also not clear.

Sandpaper

Going back to Un art de la guerre, with respect to the visual turn of the previous exhibitions, this show places Debord’s writings at its center. This return to the centrality of the written word follows the publication by Gallimard, in 2004, of his ‘Complete Works’, running to nearly 2000 pages. Asger Jorn’s pictures are little more than links between the documents, although the meeting between the two artists in 1955 marked the internationalization of the movement. The exhibition does not give them any significance in their own right. This is also true for Jacqueline de Jong, who joined the group in 1961, and for the Spur group. Debord’s films too are projected outside the main exhibition space. The same is also true for images of Debord himself. As with Maurice Blanchot and Thomas Pynchon, there are very few photographs of Debord in circulation, as Laurent Jeanpierre points out. Two photographs open and close the exhibition. One portrays the young Debord brandishing a knife (1951) as if to say “ here’s to the two of us”, and the other, at the end of the show, is a small photo taken in rue du Bac in 1991 of Debord sitting comfortably in a deep armchair. You can hardly see him, and the picture feels like something from a past which is no longer relevant today.

Does the exhibition Un art de la guerre mark a final archiving of the Situationist movement? Perhaps France is applying the same critical method to Situationism that it applied so successfully to one of the movement’s immediate predecessors, Surrealism? That is, considering only the literary aspect of the movement internationally valid, and neglecting the visual angle. It is hard to know what the answer is.

Debord took Paris by storm with his Hurlements en faveur de Sade, a pillar of French experimental cinema together with Traité de bave et d’éternité d’Isidore Isou that marked Debord’s affiliation with the Lettrist Movement, and with Gil Wolman’s Anticoncept. The projection of Debord’s film at the Musée de l’Homme, was interrupted on June 30, 1952, by protests from the audience. The uncut version was projected on October 13 in the Latin Quarter. Those 24 minutes of a blank screen and silence which brings Hurlements to an close mark the end of an era. Is it not strange, however, that Debord needed to show this ending of his film, or even to create an image as long as a film itself? During this same period, the Situationists interrupted the press conference for Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight (1952): “l’escroc aux sentiments”, “maître-chanteur de la souffrance”, “finis les pieds plats”. “C’est fini le temps des poètes”, they cried. In a similar vein, in order to disseminate his five political slogans - “Tous contre le spectacle”, “Dépassement de l’art”, “Réalisation de la philosophie”, “Abolition du travail aliéné”, “Non à tous les spécialistes du pouvoir, les conseils ouvriers partout” - Debord created a work of art that was a blend of painting, graphic poetry and graffito. It was a far cry indeed from the directives of political parties.

"If you feel you are a genius..."

Debord was a master of style, an artist of the revolution, who gave a precise form to both his actions and his public figure (as Daniel Blanchard, who knew him at the time of Socialisme ou Barbarie, points out). Did he make a work of art out of his life? Debord, after all, was the one who thought of his own existence in terms of an archive. If he as a strategist, he was most of all for posterity. Apparently, on his desk he placed a plaque which read: “Guy Debord a écrit sur cette table La Société du spectacle en 1966 et 1967 à Paris, au 169 de la rue Saint-Jacques”.Before ‘Panégyrique’ came out in 1989 – the only book Sollers confesses he read on the street, as he walked between the bookshop and his home – Debord published Mémoires (1958). It was an unusual title for a first book in a career. The cover was made of sandpaper in order to scratch and ruin all the other books placed near it on the bookshelf, that is, once it had become an archive. This idea was worthy of Duchamp’s Prière de toucher, with the tacky breast stuck onto the cover of a catalogue for a Surrealist exhibition in 1947. Memoires was literally fabricated by Debord and Jorn, who gathered together words and images, comics and collages, photos and caricatures. He wrote at the end of the book made up of – I forgot to mention this detail – only quotations: “je voulais parler la belle langue de mon siècle”. These quotations, of course, were not enclosed in quotation marks.

Since 2011

Since 2011