What do Kafka and Chaplin have in common? They both explore the margins of life, where exclusion from the world and from history opens up the curtains of dissimulation and accepts the cognition of pain as destiny. Is the comparison unfeasible? In Benjamin’s view, the worlds of representation are linked together with subtle ties. Aside from differences in time, place, and artistic media, there are mysterious affinities which allow us to juxtapose the two with unexpected hermeneutic results.

“Chaplin holds in his hands a genuine key to the interpretation of Kafka. Just as occurs in Chaplin’s situations, in which in a quite unparalleled way rejected and disinherited existence, eternal human agony combines with the particular circumstances of contemporary being, the monetary system, the city, the police, etc., so too in Kafka every event is Janus-faced, completely immemorial, without history and yet, at the same time, possessing the latest, journalistic topicality.”

Opening the eighth volume of Benjamin’s collected works is like entering a labyrinth where the paths do not follow a geometric pattern of any kind. They simply carry you on a path of awe and unlikely approaches. The incredible variety of themes in the book does not detract from the unifying aspect, which is one of the threads that tie together the erratically written and apparently scattered fragments. That is, the association of material and imaginative descriptions of the contemporary world with speculations that are timeless but continuously have to deal with time. There is a short-circuit constantly at play between metaphysical tension and curiosity about fragments of History.

Judith Butler talking about Walter Benjamin's notion of the gesture in Franz Kafka's parables

A distinctive feature of Benjamin’s later work, such as his Passagenwerk, and his essays on Baudelaire, was his microscopic approach and his decomposing of style. In this archive of fragments that make up Volume VIII of his Collected Work, the author reaches his apotheosis.

The editors of this new contribution to the Italian edition of Benjamin’s Complete Works have selected and ordered the material into two sections. First, ‘Fragments’ and second, ‘Paralipomena’. The fragments are brief notes, aphorisms, outlines and longer passages of unfinished essays or earlier drafts of later published work. ‘Fragments’ contains texts which, the editors inform readers in their introduction, are relatively self-sufficient and do not refer to any of the author’s finished works. They are divided into eight sub-sections. In the second section, ‘Paralipomena’, the texts are preparatory material for work which was later completed and published. Where possible, the editors have dated the material and placed it in chronological order.

This edition was overseen by the Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben. Agamben’s contribution was to shed light on the ‘genetic’ aspects of Benjamin’s work, which are far more illuminating than the division into themes that was carried out in the original German edition. As with many writers, but for Benjamin’s life’s work in particular, attempts made by editors after the author’s death to create a sense of order out of chaos do not do justice to the complexity of the textual interweaving.

Agamben’s chronological approach helps readers follow the transformation of his ideas and identify and trace the impact on his work of his influences, intellectual encounters, friendships, as well as the effect of his geographical wanderings throughout Europe.

It was not simply a philological choice – if you can call philology a ‘simple’ choice, since it is always a matter of constructing meanings. The choice was rather to adhere to the author’s style, and follow its development and progression. The attempt was to find unifying themes not so much in the organization of, or in the topics covered by, the collected works, but rather in the deeper connections of his thought processes.

After the first five volumes were published in 1993, there was a misunderstanding between Agamben and Einaudi, the publishers of the Italian edition of the Collected Works, and the project was interrupted. Years later, the editors of the German edition were assisted by Enrico Gianni and the last four volumes of the Italian ‘Opera Completa’ were finally released. Agamben’s chronological approach was maintained. The fragment quoted above, according to which Chaplin provides a key to Kafka’s world, is an example of how an image is fixed by a figure of thought, a Denkbild, or notion. If history is stripped of all its main features, of movement and transformation, observers can only see a series of snaps in which past and present and the eternal mobility of time are frozen in a paradoxically fixed moment. In Passagenwerk, Benjamin called this the “dialectic of immobility”. “Every present is determined by those images which are synchronous with it: Every Now is the Now of a certain recognizability. In it, truth is loaded to the bursting point with time… It isn’t that the past casts its light on what is present or that what is presents casts its light on what is past; rather an image is that which the Then and the Now come together, in a flash of lightning, into a constellation. An image is a dialectic of immobility.” (Walter Benjamin, [Theoretics of Knowledge, Theory of Progress], p.50).

This idea that images subvert the normal patterns of time is expressed in Benjamin’s fragments of literary criticism, which are some of the most revealing of Benjamin’s methodology. What is at stake here is the figure of the critic, his or her relationship to the text, and the historicity of both his point of view and that of the work under consideration. The frameworks of sociological and, in particular, Marxist historiography jar with the idea that a work of art should exist in its own right. The critic should be neither detached nor ineffable. Benjamin felt art intrinsically required more than criticism based on its content, that is, only on “what is expressed”. A true critic is the person who can look inside a work of art, observe the layers that it comprises, and know how to capture - under the skin of the work, or of events represented in the work - whatever subtracts itself from time and contingency. That is, the truth contained in it. In a long fragment on ‘false critique’ written in 1930-31, Benjamin stigmatized the short-sightedness of those who fail to see hidden links in texts. To learn to look inside a work of art means being more aware of how “Objective Content” and “Truth Content” are linked. In this fragment, Benjamin complained that Marxist critique in his day revealed a tight tangle of threads around the work of art, revealing content and even social trends. This did not lead inside the work of art, however. The only result was being able to make “simple statements about the work of art.” If a critic strives to find the hidden content, its nucleus of truth, he or she must use a “deductive esthetic”. That is, a transcendental definition of the work that establishes a meaning for the artistic experience which is both originating and eschatological.

And yet, precisely because it is a vehicle of Truth Content, the work of art risks losing its esthetic connotation. The concept of art as an artifice, whose function is to mediate content, is replaced by that of a direct relationship between each particular artwork and a platonic Idea of art. In another fragment written in the same period, Benjamin states that art is ephemeral It has become something else (in the phase of becoming) and will become something else (in the phase of criticism).

Concepts such as ‘critique’, ‘work of art’ and ‘becoming’ are proto-Romantic. In the period he was writing these fragments, Benjamin was drafting an essay on literary criticism, borrowing words and ideas from Friederich Schlegel. These include, most importantly, the idea of ‘infinite and immanent criticism’ This means that ‘critique’ is not just expressing esthetic judgment, but rather a practice that reveals a work of art to itself and enhances meaning, triggering a link between contingency (material content and its relationship to historical time) and infinity, which is seen as an ideal. Benjamin, in fact, considered any critique that transcended historical time “magical”. Another key concept for Benjamin was the idea of a work of art’s “survival”. The notes he took over these same years found their final form in a 1931 Essay called ‘History and Science of Literature.’ In this Essay he stated that his theory concerning the survival of artworks stemmed from the dominant idea that its survival gives away the illusion that art is a discipline in its own right. Art, in Benjamin’s view, cannot exist as an esthetic construct independently of history. It is, rather, the place where the “ruins created over time” offer critics the material with which they can pull the artwork apart and then put it together again.

Hanna Arendt said Benjamin “drilled for pearls”. Some of the finest pearls of this volume are his reflections on the unity of kitsch and folk art, contained in a long fragment dated 1929 Gesammelte Schriften, VI, pp.185-187). He states, “Folk art and kitsch should be considered once and for all […] a single movement” that passes certain content from hand to hand like relay race batons, behind the back of “what is known as great art.” These areas of collective imagination and sensitivity, still today excluded from the concept of art, are the ones that produce traces, auras and ancestral identifications.

Popular art “approaches” and “calls” people’s attention, and requires a response back. It forces questions, Benjamin writes, such as “Where? When did it happen?” “Viewers, readers and listeners” realize that the particular moment in space and time, that very position of the sun, represented in the artwork must have already been experienced at one point in their lives. The scene depicted is thus “re-actualized” and they “throw the situation that is brought to mind around ones’ shoulders, like a favorite old coat.” Benjamin claims this powerful attraction evokes the refrains of folk songs, which are an important feature of folk art. “Folk art and kitsch act upon “much more primitive, urgent concerns” and fantasy clothes reality in an oneiric aura, which illuminates the darkness of the self and of the character. It works, Benjamin claimed, “against our destiny” and we end up being dominated by the conviction that we have lived “infinitely more than we can know.”

The effect of these minor artworks is a split between the rational part of our self, which is based on an objectivized view of the world and on the relationship between and subject and an object, and the sense that we originally belonged to a whole towards which the other part tends to flow. “What we have experienced but do not know about echoes the world of the primitives, their furniture, their ornaments, their songs and pictures.” This echo touches viewers, readers and listeners in a completely different way from the way “great art” affects them. “In front of a painting by Titian or Monet we never feel the urge to pull out our watch and set it by the position of the sun in the picture.” Yet, “in the case of pictures in children’s books, or in Utrillo’s paintings, which really do recuperate the primitive, we might easily get such an urge.”

In this no-man’s land between sleep and wakefulness, where fantasy does not question itself but abandons itself to the pull of the primitive, what comes to the fore is a state of reminiscence. This is not a Platonic anamnesis, but rather a feeling of déja-vu. This feeling “is changed from the pathological exception that it is in civilized life to a magical ability at whose disposal folk art (no less than kitsch) places itself.”

Walter Benjamin's Memorial, Portbou

Benjamin calls uncontrolled memories that rush back from a distant past “masks of fate”. These masks, like those of the primitives, in Benjamin’s view, take over our fragile plan to find meaning.

Great art and kitsch. Art with a capital letter, and folk art. To conduct a critique is to go beyond esthetic judgement. It is not a matter of what is beautiful or ugly, nor of style or taste. Benjamin highlights a polarity. On the one hand, there is the modern, Cartesian, illuminist then Kantian, idea of a subject – the subject that claims to control the world using rationality and thinks art idealizes human life by imposing formal style. On the other, there is a dimension of the self that is governed by the power of myth, by the design of fate, and by the collective unconscious.

This train of thought preserves its analytical force even when it is applied to the variegated world of pop culture today. Benjamin concluded by making an implicit reference to the concept of critique. “Art teaches us to look into objects. Folk art and kitsch allow us to look outward from within these objects.”

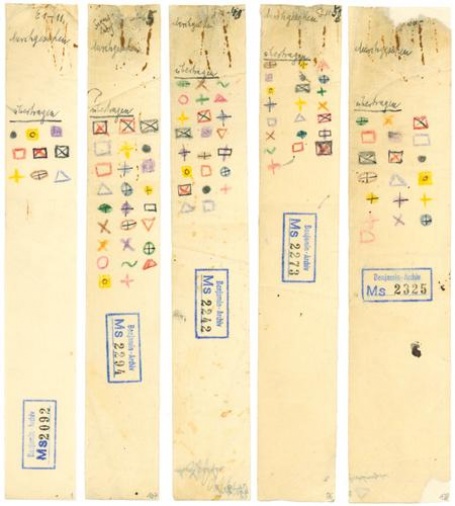

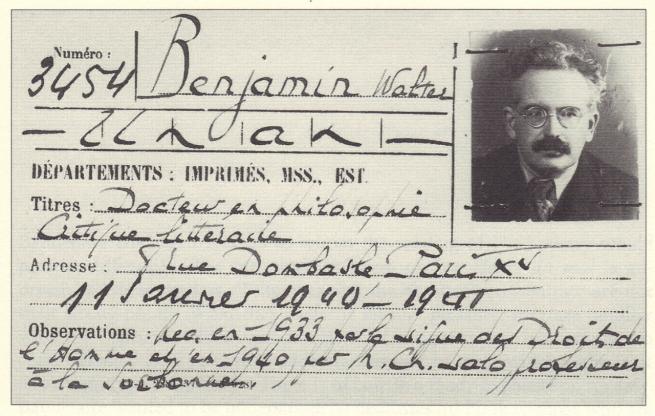

As the 2011 exhibition, ‘Walter Benjamin Archives’, curated in Paris by the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, showed so clearly, minimalism is one of the main traits of Benjamin’s essay writing, together with listing, citation, and note fragments. The very materiality of his cramped handwriting, which challenges us to decipher it, the montage effect of disparate elements gathered together, the search for conceptual synesthesia – all these elements contribute to our understanding of the essays.

The fragments offer readers a close-up view and significant insight into Walter Benjamin’s philosophical leanings. We can appraise his tools, understand the provenance of his materials, see the maps and papers that led to diverse re-constructions. It is like a vast construction site, and it is easy to imagine Benjamin working there, dressed as a wizard, with a cap and wand, as Adorno described him.

Since 2011

Since 2011