0.45 GMT – 05.15 in Afghanistan.

Pilot: Shit, is that a rifle?

Operator: Dunno, it’s just a warm spot where he’s sitting, I can’t really say, it looks like an object though.

Pilot: I hoped there was a weapon down there. Oh well.

01.45

Operator: That truck would be a good target. It’s a 4 x 4 Chevrolet, a Chevy Suburban.

Pilot: Yes.

Operator: Oh yes.

01.07

Coordinator: The screener says there’s at least one child near the 4 x 4

Operator: Fuck… where?

Operator: Send me a fucking image, but I don’t think there are kids around at this time of night. I know these guys are weird, but…

Operator: Dunno, could be a teenager, anyway I haven’t seen anything small and they are all bunched together there.

This is a transcript of part of a conversation between members of a ‘team’ guiding a Predator drone over the Afghan skies on February 20, 2010. They are sitting comfortably in their chairs on the Creech US Army Base. The exchange goes on for several minutes, grows agitated, and then draws to a close when a missile is launched and two Kiowa helicopters arrive on the scene, having been called in to complete the attack against the intercepted Chevy.

The transcript is cited by the French historian and philosopher Grégoire Chamayou in his new book, Drone Theory (Penguin, 2015). At the end of their shift - as the American writer and journalist, William Lange Langewiesche, describes in his long Vanity Fair article, The Distant Executioner (Feb., 2010) - the pilot and the operator climb into their cars, drive back to their homes in the Las Vegas suburbs, and hug their wives and kids. Another team takes the next shift.

Both these works analyze the role of drones, the latest tool of surveillance and punishment, which is increasingly under critical scrutiny in the US and European print media. Mark Bowden, author of The Finish: the Killing of Osama Bin Laden (Grove Press/Atlantic Monthly Press, 2012), published his contribution to the drone debate in The Atlantic (‘The Killing Machines’, Aug., 2014).

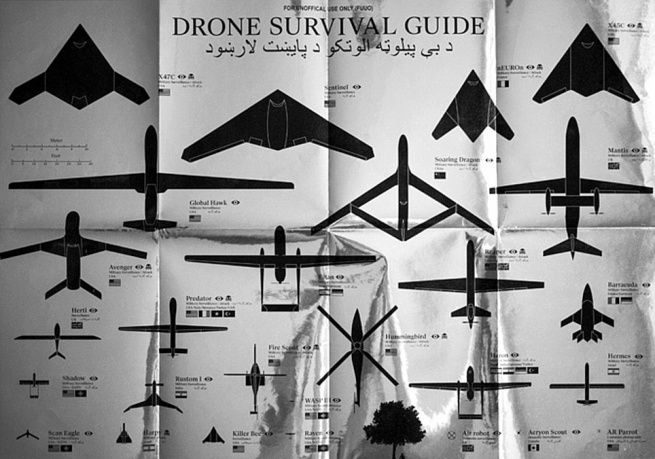

Since 9/11, drones – whose name refers to the insect-like buzzing noise they make – have been used increasingly by the US Army and the CIA for carrying out missions on foreign soil without mobilizing US soldiers on the ground. Their technical name is Remotely Piloted Aircraft, or RPAs. The operators, in fact, pilot the planes from their seats on the base. The RPAs are their range-viewers for observing enemy territory more than 8,000 miles away, from an altitude of nearly 2 miles above land. Langewiesche describes how the RPAs are actually planes minus the pilot’s seat, which stays on the ground. They are a set of eyes watching over populations in areas where guerilla warfare or low intensity fighting is underway, under American military alert.

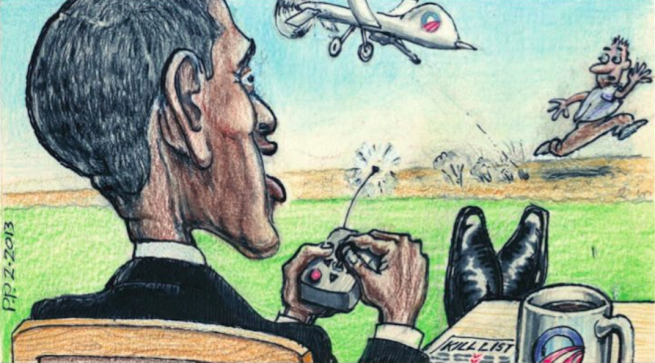

Drone warfare has intensified since Obama came to power, as Pulitzer Prize winner Mark Mazzetti has shown in his latest book, The Way of the Knife: The CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth (Penguin, 2014). According to this investigative journalist, the drones are often ‘piloted’ by civilian CIA operatives. In the last chapter of his highly detailed account, Mazzzetti describes the assassination of al-Awlaki, a US citizen and Islamic leader in Detroit, with links to al-Qaeda and Bin Laden. Two weeks after his death, al-Awkalki’s son was sitting with friends in an outdoor restaurant near Azzan in the Yemen when he heard the unmistakable buzz of a drone in the distance. The missile inexorably found its target. Mazzetti writes that the son was not on any wanted list, nor was he on the CIA hit-list of planned targets approved weekly by the President. It was chalked down as a mistake. Chamayou cites US Air Force research that claims drones are the low-cost weapon of choice, both because they purportedly save human lives and because they save money. Precisely because drones are a substitute for ground soldiers they are defined by US Army strategists as “humanitarian weapons par excellence”.

The invention of drones dates back to 1964, when the engineer, John W. Clark, conducted preliminary research on “methodologies for hostile environments”. Clark’s intuition was to find a way to control machines remotely – what he called “remote handling technology” – in hostile environments where human life was endangered. In the same years, science-fiction books and films were filled with futuristic robotic warfare unencumbered by foot soldiers, machines competing against each other with no human victims. In 1965, Susan Sontag published an article on American science- fiction B movies entitled The Imagination of Disaster, which was then included in her 1966 collection Against Interpretation and other Essays (Farrah, Strauss & Giroux, 1966).

Chamayou backdates the conception of the first drone and illustrates how the idea was actually born in Hollywood. In 1944, a former star of the silent movies started producing model airplanes. Today’s drones, Chamayou writes, were still in the realm of “make-believe” but during World War II similar remote devices were used to train the military. Drones were not actively employed in warfare until 1973 during the Yom Kippur War. The Israeli Army, ahead of its time, used pilotless planes – little more than airplane models – to bait, and subsequently identify, Egyptian anti-air missiles. Sure enough, the Egyptians fired their missiles at the diminutive planes, upon which the Israelis pointed their counter-missiles and fired. In later years, the Israeli Army produced a drone known as the Mastiff which was employed to spy on enemy positions.

In order to trace the inception of contemporary drones, however, we need to go back to the spy planes used by Americans during the Cold War. In his book entitled War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, (Zone Books, 1991), the Mexican filmmaker, writer, performer and researcher of complexity, Manuel De Landa takes a novel approach to the progress of technological warfare. He views the development through the eyes of a future robot who has been given the task of drafting a historical account of war technology since the first Gulf War. Intelligent bombs, self-guided missiles, and drones themselves all incorporate human cognitive structures in their machinery. De Landa refers to the works of Deleuze and Guattari, and cites both chaos and game theory. He reconstructs the history of attempts to recreate the human body in machines, from the seventeenth century, to Napoleon, and on to the cybernetic satellite theories of the 1980s.

Chamayou, on the other hand, focusses on the implied human responsibility, and discusses the ethical premises and consequences of the relationship between man and machine. Human operators “watch” from a distance and decide, on the basis of their experience and of pre-established protocols, whether to take action or not. Whether or not, that is, to push a button and launch a missile that has the capacity to kill men, women and children and blow up vehicles and buildings. While Landa believes the human factor is remote and incorporated by machines, Chamayou, according to the post-human vision of his time, considers human beings vital to the functioning of these flying machines. Ground teams today use the mechanical eye of the drone as an observation tool in order to decide on action. It is by no means impossible to imagine a future development whereby the eyes on the ground are as automated as the strike.

Warfare is no longer a matter of occupying a territory by traversing it with troops and mechanical vehicles. Nowadays what counts is controlling a territory from above, thus guaranteeing supremacy from the skies. In his book, Terror from the Air, (Semiotext(e), 2009), Peter Sloterdijk traces the transition from traditional warfare towards controlling the ‘atmosphere’. The historian dates the shift as far back as Germany’s use of chlorine gas in World War I trenches. Eyal Weizman, an Israeli forensic architect who has written a book on the wall separating Israelis and Palestinians called Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation, (Verso, 2007), quotes a motto popular in Israel today: “Technology not Occupation.” Drones could be considered part of this strategy that aims to make supremacy vertical. They are a form of extra-territorial authority.

In contemporary war theory, air space is no longer seen as being continuous or homogenous, as it was in World War II. Now, air space is considered a patchwork of slots, each with different rules of engagement. The slots, Chamayou states, are actually cubes. Drone operators see them as a series of boxes, placed side by side, marking out the air space. They are sometimes called “kill boxes”. “Imagine a series of boxes lined up in a grid on a 3D screen,” Chamayou writes, “ […] The theatre of operations is no more than a string of transparent boxes.” How does this screen image suspended between virtual reality and actuality work? There are three-dimensional zones of action: “if you are inside your box, shoot to your heart’s content!” The mosaic structure makes the attack an abstraction. Operators check their screens and pinpoint their target, as if they were playing a video game. It is reminiscent of the fighting in Star Wars (1977), a precursor of all the digital warfare that was to follow.

The sky - the vertical space ––is not the only space increasingly being occupied by vehicles without pilots, examples of which include the small aircraft with missiles in their bellies, known as the Predator and the Reaper. Miniature drones are on their way: self-sufficient robotic insects that can fly in smaller and smaller spaces. Chamayou predicts that bedrooms and offices could well become war zones if these tiny flying robots take off. The box on the screen would be as little as a square inch. Rather than blowing up a whole building in order to eliminate an alleged terrorist, an enemy combatant could be wiped out in his or her own apartment. The remote-controlled explosion would be limited to one room, or even one body, with everything else left intact. These miniature drones are the technological answer to the recent spate of suicide bombers. If Carl Schmitt were to write his Theory of the Partisan today, Chamayou surmises, he would not refer to the nomos of the Earth, but rather to the stratosphere, or the sky. Air space has become, as Sloterdijk pointed out, the focus of conflict.

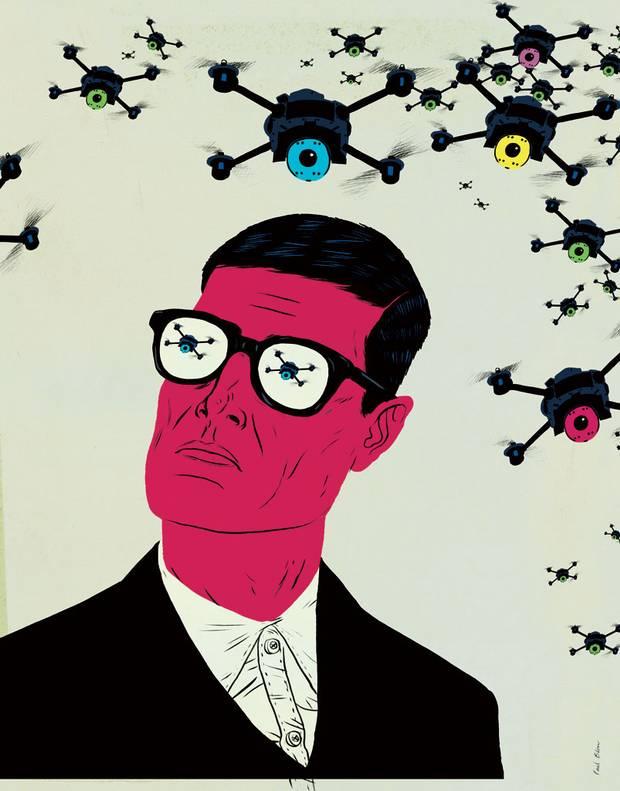

Today’s drones can fly for days. They provide non-stop vigilance 24/7. Chamayou adopts the metaphor of a “mechanical eye with no eyelids”. While the drone is flying, three teams on eight-hour shifts cover the 24 hours. It is a “constant geospatial vigil” conducted by “the eye of the state”. It is reminiscent of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Vintage Books, 1995), except that Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, where prison guards were able to keep an eye on prisoners day and night because their cells were arranged in a semi-circle around them, has been replaced by a drone. The observation area is ever wider: immense swathes of enemy territory can now be surveyed (“wide area surveillance”). Chamayou also talks about the future of “synoptic iconography”. That is, a number of high resolution micro-cameras - like the multiple eyes of insects - that capture images, which are then put together and processed in real time by a software program. Partial views thus create a single overview, with an infinite possibility of adding more and more details. Furthermore, drones can intercept electronic and cell phone data as well as other forms of telecommunications. Sensitive data can then be recalled to the ground computers back at the US base, sheltered away from the world. The information garnered in this way can then be used to take action in the areas under surveillance. Eyes and ears at a distance. One supporter of total surveillance powers within the US Air Force claims that if it were possible to keep a whole city under surveillance of this kind, it would also be possible to detect a car-bomb as it is being loaded into a vehicle. The memory capacity of today’s computers means we are not too far off, at least in theory. In 2009, American drones stored data that was the equivalent of 24 years of video recordings.

At the roots of this visual development, lies American sport. Lt. Gen. James, until 2013 Air Force Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance at the Pentagon, once said that in terms of data collection, sports TV is way ahead of the military. The software required by television stations that cover sports’ events – Basketball, Baseball, American Football – is highly sophisticated. TV cameras film different viewpoints of the game, provide instant virtual re-play of game action, and produce statistics on the athletes’ movements. The military is having to play catch-up. In his Theories of German Fascism, a remarkably far-sighted article written in the 1930s in a collection of essays edited by Ernst Jűnger, Walter Benjamin predicted that future warfare would do away with traditional military categories and take on those of sport: “war of the future”, he claimed, will have “a face which permanently displaces soldierly qualities by those of sports.” The sophistication of all this visual technology - the recording and archiving of images and data – proves that Manuel De Landa’s predictions were not that far off the mark. Machines might well, as Chamayou himself states, automatically attach megadata or tags and use sophisticated programs or algorithms, such as those used to investigate and classify the tastes of those who frequent social network sites. The ghost of a “machine-scribe” haunts the air. A flying archivist, capturing and recording in real time every minimal activity that takes place down there in the war zone under its gaze. Everybody, at that point, would be susceptible to “searches”, whether they are in Afghanistan or in Italy, in Somalia or in the United States.

Our view of the world changes radically from this perspective. When we fly over an area, from the airplane window we see the seductive layout of the land below us. A drone, however, thanks to the chrono-geographical diagrams elaborated in the 1960s by the Swedish geographer Torsten Hägerstrand, sees everything – what, where, when - in three dimensions. “Geography is meant, above all, to wage war”, Yves Lacoste titled his 1985 book (Editions Decouverte). The academic world was scandalized, but the book’s message still holds true today. Cartographers set out to create three-dimensional maps which would highlight people’s life-paths in order to predict accidents or impede any form of deviation. Now that vision has become a cornerstone of “armed surveillance”.

The aim is to follow a plurality of individuals through their activity on social networks and trace a pattern of their activities so that any seditious activity or sparks of revolt can be picked up in advance or in real time. An Air Force analyst has claimed that drone activity, currently killing on demand in Afghanistan and in other hotspots, is halfway between the work of a detective and that of a social scientist.

The issue is understanding “forms of life” (a concept borrowed from phenomenology, which had a very different aim in mind) and possible deviations from models that are considered ‘normal’. Just as the Liberal Arts are being deserted by students, and starved of resources, across American and European universities, this strongly Humanistic field of study is beginning to interest the military, army strategists and secret service operatives. As drone technology shows, you cannot gain knowledge of the future without acquiring knowledge of the past.

One of Chamayou’s strongest arguments is that war is no longer considered a duel, in the Clausewitz tradition. It is now seen as a hunt. The idea was already present in his previous work, Manhunts, a Philosophical History (Princeton University Press, 2012), in which he stated that the war paradigm was no longer “two wrestlers” fighting, but “a hunter stalking” an elusive prey. The primary objective of today’s warfare, Chamayou pointed out in this earlier work, is not to immobilize your enemies, but to identify and localize them. This, of course, requires extensive investigation. Connection topography, adopted by companies to draw profiles of social network users and create models for potential clients, is now at the heart of military cartography. Internet topologies are used to bring about social “forums” that forge links from individual to individual. The enemy is no longer seen as a link in a hierarchical chain of command, but as a nodal point in a network. There are often ‘left-leaning’ authors such as Deleuze or Guattari behind these war theories. Their highly subversive book, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), is used by the Israeli Armed Forces to think topographically about military strategy in Palestinian refugee camps.

Another important point Chamayou makes is that drones are a weapon of state terrorism. These flying machines surveying enemy territory are tactical not strategic weapons. The very idea of strategy is becoming obsolescent in the face of the abnormal upgrading of tactics. Electronic gadgets are leading to the end of strategic planning, which has always been linked to political choices, and to the decisions of political commanders-in-chief in the event of war. Today’s technological knowhow, the domination of computers and related technology, has led to the deterioration of politics as a system for orienting choices. Every decision the military demands the executive branch carry out nowadays is tactical. Tactics is today’s strategy.

Chamayou is pessimistic (as well as being subliminally fascinated by drones). His book makes you think about how new technologies, based on a spirit of collaboration – “the intelligence of the crowd” he calls it - can nevertheless contribute to limiting individual liberties rather than widening them, as one would have imagined. The jury is still out. However, Chamayou makes it very clear that sections of the US Administration, which are still in power despite a change of President, are using, and will continue to use, the new technology available to wage war and to exercise control over enemy territory.

The final chapters of Drone Theory pose the basic issue of whether drones are morally acceptable. Chamayoux examines in great detail the various legal arguments that have been adopted, and analyzes theories put forward by American military academies, intellectuals, researchers and strategists. There is one question that comes to mind on discovering how widespread drones are, not only in the military sphere. To what extent could drones be used for peaceful purposes?

Chamayou describes how there is exponential growth in the use of drones in various subcultures. These DIY drones are often home manufactured, and find unlikely champions in figures such as Francis Fukuyama, author of The End of History and the Last Man (Free Press, 1992) who is a passionate drone builder and blogs about his constructions. Chris Anderson, author, among other books, of Makers: the New Industrial Revolution (Crown Publishing, 2014) resigned from Wired magazine and founded 3D Robotics, a company that produces 100 drones a month using 3D technology. Drones are used in many non-military areas: architecture, archeology, forestry, chartered surveying, and more. Equipped with mini video cameras, these relatively inexpensive machines (Anderson sells them at 600 dollars apiece) offer an extraordinary birds-eye view of the world we live in.

Chamayou cites Walter Benjamin’s theory that technology may realize its emancipatory potential when it is not death-bent. By re-animating its esthetic and game function, intrinsic in any technological object, its real spirit is freed. I don’t know whether this can provide us with hope that something different from the terrible use of drones in low intensity warfare, or in the hunting of terrorists, will come about. Amateur drones are potentially a tool for peace. Their watchful eye is not necessarily an instrument of death.

Since 2011

Since 2011