Persistent in the canon of art history, the equation Nature=Impressionism survives today. At the turn of the twentieth century, French critics already claimed that the Impressionists’ attention to perception was a route to come closer to Nature – a strive for perfect mimesis. Historiography, moreover, has placed the essence of impressionism in the consonance between the use of a free brush and the impermanence of Nature. Soon enough, Seurat’s geometrical marks would have brought to an end the phase of pictorial spontaneity and experiment, moving the potential of expression towards optical rules. Beyond these, only abstraction remained to the painter of Nature. This narrative of Impressionism as an unsurpassed milestone in the representation of Nature is stronger than ever, and attracts masses of tourists in museums from Paris to Washington and Tokyo, such narrative. Yet, the world of Pissarro, Monet, and Seurat remains opaque if one persists in reading the history Impressionism as one of mimesis and style. Instead, we should think perhaps about Nature as the unresolved subject of representation. Consider the first of the Impressionists, Camille Pissarro: what to make of the tenacious struggle to paint rural life and peasants? A fresh look at his late paintings reveals a different idea of Nature, and of landscape.

La récolte des pommes à Éragny, 1888

In his last twenty years, Pissarro used techniques which distort, at least in part, his reassuring identity as the ‘father of the Impressionists’ (Paul Cézanne). He experimented with a variety of supports: silk fans, canvases with a rough texture, drawings in graphite, chalk or watercolour, and woodcuts. These attempts can be read as the final trials of an artist worn out by the search for a language: in this phase, Pissarro alternates scenes of everyday life of the petit bourgeois tending their plants to visions of shepherds and peasants working in the fields, almost transfigured through the use of bright colours imparting an epic tone to the scenes. Today we would call it the ‘fieldwork’ of an anthropologist, literally the work-in-the-field of a man who spent a life observing, and participating, to the peasant life of the Parisian countryside. In a letter to his son Lucien of 1883, Pissarro wrote: ‘Remember that I have the temperament of a peasant, I am melancholy, harsh and savage in my works, it is only in the long run that I can expect to please’. What relation between the urgency to represent these workers, the heated political debate, and the history of Impressionism? As T.J. Clark has remarked, (in Farewell to an Idea, 1999), the paintings on show at the personal exhibition of 1891 addressed the tensions of modernity (and modernism), while trying to explore the limits of pictorial language. That’s why it is still so hard to interpret Pissarro’s last phase, and why it’s still worth trying.

Travaux des champs. Femmes

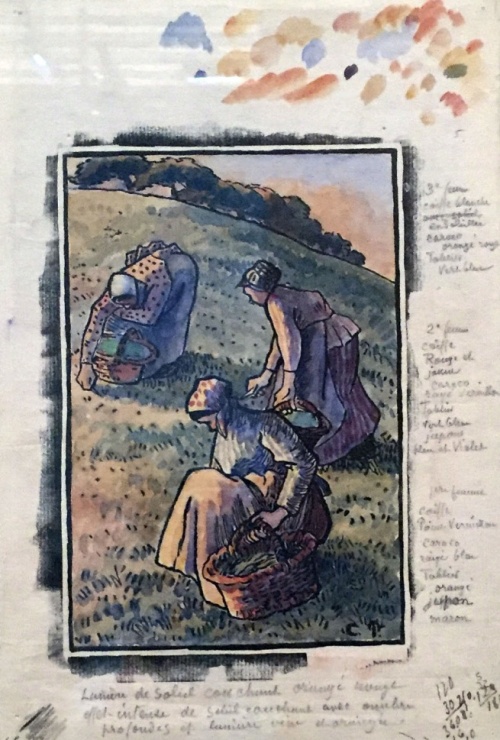

The Travaux des champs, a series of vignettes whose slow development took the last twenty years of Pissarro’s life, can be seen as his artistic legacy. These scenes of rural life were meant to form an illustrated book that collected texts by contemporary authors or excerpts from Virgil’s Bucolics, but only a few were actually published. Hundreds of preparatory drawings survive today, along with print proofs covered in annotations on colour and composition, which Pissarro sent to Lucien, printmaker and publisher based in London. From this correspondence emerges a tension between the attempt to describe such fast-evolving social reality and the utopic dream promoted by the radical left. The series is divided into sub-categories corresponding to different times of the day, social rituals, personal status: a country wedding, the market day, the harvesting season, etc. In a hand-coloured proof, three peasant women are picking weeds by hand or with small cutting tools, bent on their knees, bearing no attention to one another, while an intense red light marks the end of the working day.

As with the rest of Pissarro’s pictorial oeuvre, women are faceless heroines of rural life: they reveal their courage at such difficult times when most men have been sent to war or to the nearby factories. Absorbed in their task, holding down their gaze, these peasant women bring to mind Chardin’s maids and mothers. Yet, their fate is different from that of their eighteenth century antecedents, as Pissarro’s women can pause for a few instants to look at the tinted light of dusk and admire Nature. While Chardin’s maids are confined to the interior of the house, at least Pissarro’s peasant women can enjoy the beauty of a sunset. In several letters, Pissarro remarks on the need to express the range of colours of the evening sky. The mark of his preparatory drawings is extremely simplified while the watercolour strokes impart a melancholy yet lyrical atmosphere, though it may last only a few moments. This modern pastoral is a form of representation of that transient moment of self-awareness that Michael Fried has called absorption, rather than a tribute to some idyllic country.

An ample selection of the Travaux des champs is found in a dedicated room at the centre of the exhibition Pissarro a Eragny: la nature retrouvée (Palais du Luxembourg, until 9 July 2017). This room feels like a welcome interruption in the tight sequence of rural paintings made by the artist in the village of Eragny-sur-Terne between 1884, when he moved there with his family, and his death in 1903. The Travaux is a strong series, speaking more explicitly than any picture on show about Pissarro’s iconographic interest. What if, instead of an interruption or a side-project, they were to be considered as the centre of Pissarro’s last phase and even as the key to understand his oeuvre retrospectively?

In the early days Pisarro tended to place his figures in a subordinate role in relation to the landscape. The figures are seen working in the fields or walking along the roads, but usually in the middle or far distance, and often forming part of a broad panorama which dominates the picture and contains the figures. They are related to the landscape only so far as they are integrated with their surroundings. The best example of such approach is a view of the banks of the Marne exhibited at the Salon in 1864, where a solitary figure at the centre is walking at dusk. This canvas is on show at the retrospective exhibition of Pissarro’s work at the Musée Marmottan Monet (until 16 July 2017), which complements that at the Luxembourg. The exhibitions could not be more different: one seems to stretch the final years, showing even the most commercially viable works, the other brings together a whole life in a selection of about seventy highlights. Yet, both end up restating the trite narrative device of Nature instead of shifting the focus on labour, choosing to confirm Pissarro’s formal continuity with a preconceived idea of Impressionism rather than his political radicalism. The works which address most directly the social inequalities of the time really look out of place in such narration. For Pissarro, however, the idealist vision of nature shared by anarchists and symbolists was inacceptable, and his materialism would bring him to condemn any concession to sentimentalism. Instead, he tried to remain faithful to the landscape he knew, that landscape transformed by History and Man: his observation field. Eragny was a very appropriate place for this type of enquiry – an anonymous village where the new bourgeoisie was in conflict with the peasants who had been working on site for generations. Pissarro bought a large house with a studio for his large family with the help of a friend, participating to such social contradictions. The idea of a Nature retrouvée – the subtitle to the Luxembourg exhibition – is not really applicable to the work produced at Eragny: Pissarro was closer to Nature when he worked en plein air, but in the last twenty years he mostly painted in his studio at the first floor of the house, looking at the landscape from a large window.

The crowd obstructs the view of the paintings from a distance, forcing me to scrutinise the brush strokes that the artist used to make this modest, unassuming nature more expressive. This condition forces me to notice the gilded frames, some certainly rococo, that spoil the delicacy of some pictures’ colour scheme. I wonder what in these paintings might have lured those collectors who, immediately after Pissarro’s death, rushed to buy his pictures, while when he was alive had preferred the (perhaps more coherent) work of his colleagues. Would they have seen in them the social contradictions so subtly expressed? After the great victory of the left at the Parlamentary election of 1890 the republican Jules Ferry wrote to a colleague: ‘Our victory is rural, not urban.’ Then as today, the petit bourgeoisie of the countryside felt to any astute observer as a unique, distinct body with its political authority. Pissarro was conscious of such issues and responded with his materialist approach. Above and beyond the search for a formal language, towards the end he had pursued primarily a study of the peasant labourer in relation to her landscape – a self-portrait in disguise.

Since 2011

Since 2011