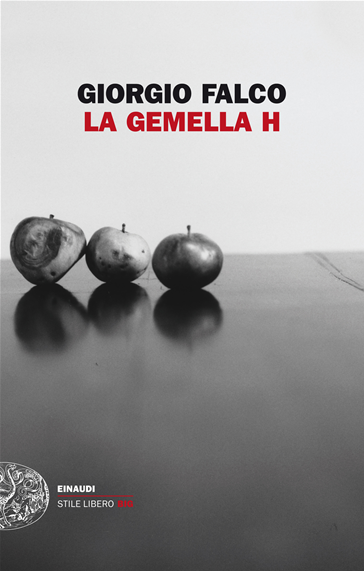

Three slightly rotten looking apples on a leaning shelf, indefinite shadows like pools beneath them. The black and white photo on the cover of the Italian edition of the book, by Sabina Ragucci, evokes the idea of time passing.

Apples come into the first sentence, and become part of a discreet but insistent refrain in the book. The protagonist, and narrative voice for much of Giorgio Falco’s new book, La Gemella H ("Twin H", Einaudi 2014) sings the refrain to herself repeatedly: “we only ate apples in strudel in the beginning.” After Pausa caffè ("Coffee Break", Sironi 2004) and the magnificent short stories collected under the title L’ubicazione del bene, ("The Location of Good", Einaudi 2009), Falco tells the story of Hilde Hinner, endowed with the almost magical ability to describe both her own and her sister Helga’s life since their birth in 1933 – her sister the elder by a few minutes.

Hilde tries to become independent by taking up a job as a shop assistant at the Rinascente department store, horribly rebuilt after the ravages of war, but she soon returns to the fold. The twin sisters lives follow a parallel path almost to the bitter end. Identical in appearance, their inner lives are however divided by a thin grey line that is almost invisible but ever-present. The novel could be summed up as a painfully calm attempt to give consistency – if not a name – to this thin line.

Grey is a key color in La Gemella H, as the cover photograph suggests. Giorgio Falco bravely decided to write his novel in shades of grey. Readers of his previous books were accustomed to strong, metallic colors, a hammering beat, sudden accelerations, but in ‘Twin H’, his writing is captivating, lingering, almost cloying (except for brief flashes, such as the virtuoso description of galloping horses in a race at the Merano hippodrome.

In his previous work, Falco adopted an accelerated present tense narrative technique he learned from James G. Ballard to make the future loom threateningly. In ‘Twin H’ he uses another technique that is no less effective. That is, a delayed past, a past that never seems to pass, and thus digs deeply into the secrets of the present. Lead grey is the dominant shade. At one point it is associated with the “ethical quality of the Adriatic sea” which “reminds us every now and then who we are”. Other associations that come to mind are ‘The White Ribbon’, an unsettling 2009 film by Michael Haneke, and August Sander’s famous portrait photographs. By producing in the 1920s thousands of images of “ordinary twentieth century people” Sander hoped to create an exhaustive ‘Atlas of the German Nation’ subdivided into categories. Sander, whose son was later to be deported, captures images of both Nazi youths and their future victims, their gypsy and homosexual peers.

Walter Benjamin concluded a 1931 essay, A Short History of Photography, by saying that Sander’s work “from one moment to the next could well take on unexpected relevance.” In 1933, the same year the twins were born, the Nazi regime was established. That social body, and that system of proxemics and physiognomy, would lead to catastrophe. QED. Hilde Hinner, after a brief flirt in Munich with a young man who wanted to carry on Sander’s work, aims to undertake a similar project. She takes copious notes that she plans to tidy up one day. Words on paper she is not allowed to pronounce (“We never talked about Hitler when Hitler was there and we were living in Hitler’s nation: shall we talk about Hitler now, at the seaside?”, “Until now I’ve been pretending, with my father, my sister, with everyone. They want me to have a normal life, all they talk about is the present and building a future. They never talk about the past, or where we come from.”). Hilde dedicates herself to photography. She takes Polaroids of the mostly German guests in the modest but profitable pension her father Hans set up after the war on the Adriatic Riviera. After the first pictures, with their banal “tourist smiles”, the German faces melt back into the milky greyness of their everyday lives. They complain: “ that’s not what we really look like.” Hilda gives them the first photo, the one the guests want, and she keeps all the others, to create an archive. She compiles her own court records.

“We only ate apples in strudel in the beginning”. Then what happened? What happened after that beginning that can’t be talked about? What was it that made calm wellbeing possible without any questions about later? Where is the line drawn between before and after, and why can’t it be named? These are the questions Hilde seeks to answer. Where does that letter H that is branded on her destiny, like the letter for Truth on the Golem’s forehead, come from? As in Alexander Sokurov’s film ‘Moloch’, where pale colors dominate in Hitler’s hideaway in the Bavarian Alps, the only weak links with reality are the letter H hinted at evanescently: the doctor responsible for his inseparable dog’s death, or his food manias.

The twins’ mother is ill and takes her daughters to milder climates, first in Merano and then to the seaside at Milano Marittima. Meanwhile, Hans, their father, does everything in his power to make himself a typical example of the petit bourgeoisie. He is perennially dissatisfied and consumed with repressed anger. Qualities that were to be cornerstones of the Nazi movement. A minor journalist in a local newspaper in the small Bavarian town of Blockburg (where apparent calm and order reigned, like in the early twentieth century village in Haneke’s film), Hans accompanies the devastating rise of the new party by transforming his backwater journal ‘Mutter’ (Germany, pale mother) into a fanatic propaganda megaphone. From this transformation the twins’ father accrues the respect of the community and significant financial benefit.

The Blumenstein bank from which he had taken out his mortgage finds itself forced to extinguish the loan. Neighbors who happened to have bigger houses, more luxurious cars, or, in the case of the Kaumann family, an Alsatian with shinier fur, suddenly find that their possessions have been expropriated, or are forced to sell everything to the now powerful journalist. Hilde’s perspective, as she plays in the garden with her toys, brings to mind our equally detached but horrified gaze in one of the most traumatic scenes of Polanski’s film, ‘The Pianist’, when we watch impotently as an old man in a wheelchair is thrown out of a window by an SS soldier in the Warsaw Ghetto. Nobody in Blockburg talks about Jews. Least of all about the Final Solution.

It was not with these stolen possessions, however, that Hans Hinner was able to start a new life in Italy when disaster struck. Mr. Hinner takes his silence to the grave, but despite everything he still believes that his world was the winner. A world which has plummeted into the grey depths of daily life as a “form of denial”. The unconscious but deliberate collaboration of “the succumbed” to those who dominated them. The “populace” that “likes to have a bit of fun, to become someone” and “follow the flow of events dressed up in money.” Nobody asks about this money, it is “laundered by the expiation of seasonal work […] All you need to do is wait for the sea water to come and wipe away all the signs, then start again.” Hans’s legacy is that the twins inherit the grey line that differentiates them. Hilde is unable to voice her apprehension, while Helga follows completely in her father’s footsteps , later herself working in the hotel business.

If tourism, as Ernst Jünger and Ballard taught us, is a form of low intensity warfare, Hinner’s resistible rise shows that petit bourgeois consumerism in the form of holiday rentals is, on a more subtle level, a form of low intensity regime. The same ambiguities, the same complicities, the same silences. It is again merely hinted at, but it is highly significant. Helga wants her father to employ a fascist youth she met on the beach as a cook. The problem is that the pension already has Signora Margherita, a very competent, though rustic, cook from the Romagna region on its books. Helga’s solution is to put three apples into the cook’s bag and accuse her of robbery. One of the apples falls out of her bag, and Margherita is left speechless. Hilde picks the apple up. Hilde has seen everything, but again says nothing. She stares at the apple as if it were an omen, as if it were possible to “predict the future from traces of the past.” Beyond the reassuring consumerist, cosmetic nature of the strudel, the apple really is the fruit of Good and Evil. In this opaque mirror, suddenly Hilde sees she belongs to the grey area.

With the courage of his convictions, Falco has achieved the impossible. Jonathan Littell’s controversial book The Kindly Ones (Harper Collins, 2009) was praised by critics for having finally overturned what Daniele Giglioli, in his Critica della vittima ("Criticism of the Victim") calls “the victimist paradigm” (that is, a self-absolutory identification with victims throughout history). However, taking on the point of view of the tormentor in the exaggerated form of Littell’s character Maximilian Aue does little more than stress the inverted paradigm. It convinces us we are not of the same ilk. We have nothing in common with a monster of that kind. Very few writers have had the courage to take on the point of view of the Grey Area. The slippery area that comprises not only the complicity of the victims, as portrayed by Primo Levi, but also the silence of witnesses, that rejection of speech that made then accomplices.

This is the burning mirror. It burns your eyes out. After Hilde embraced the truth, even Helga learns. “It is as if the world were doubled, as if it separated itself in order to show its real face.” The image of the mirror is painful to read. It slices us in two. It must have been just as hard for the writer to find an end for this book. However, only by undergoing tests of this kind can we finally learn to reveal ourselves for what we really are.

Since 2011

Since 2011