The first edition of the Mois de la Photographie, held at the Institut Français of Cotonou, has showcased the work of four Beninese and French photographers – Laeïla Adjovi, Léonce Agbodjelou, Jean-Jacques Moles, and Catherine Laurent – all focusing on contemporary Benin. The exhibition shed light on a little-known scenario, less established and thriving than that of other countries, such as neighboring Nigeria, but increasingly aware of its striking potential (as clearly emerges from the pictures showcased and other projects). Art and culture in Benin are significantly supported by the Institut Français, the French government agency for the promotion of French culture overseas , and Fondation Zinsou, a local foundation operating in the visual arts field and committed to broadening access to reading through a network of mini-libraries spread across the country.

Placed next to each other, the works of these four photographers – exhibited in Cotonou from January to March, 2016 – sketch out the image of a country caught between past and future, between the certainties of traditional community life and the challenges of individual freedom, between the remnants of a long and layered history (the ancient Kingdom of Dahomey, Portuguese and French colonization, voodoo rituals, the slave trade in Ouidah, Porto Novo’s Afro-Brazilian culture, and the “African Cuba” communist experiment between the 1970s and the 1980s) and the pressures of an ambivalent modernity (the troublesome post-colonial “tutelage” by the French and the religious violence in the neighboring countries of Nigeria and Burkina-Faso).

The common ground and meeting place for all these tensions is the body, which French-Beninese photographer Laeïla Adjovi represents through the traditional practice of scarification in the series entitled La Figure du clan.

This practice had already drawn the attention of another Beninese photographer, Erick Ahounou, in the early 2000s when he started classifying scarifications in the form of a visual atlas, perhaps with an ironic reference to the positivist ethnographic approach. Adjovi distances herself from this objectifying perspective, her style harking back to the reports made during the golden age of ethnography (Malinowski, Boas, Lévi-Strauss). Her work focuses on subjectivity, on the adherence to, or refusal of, community marks indelibly inscribed in the body, particularly on the face, the most important cue for individual recognition. The photographic act is conceived as a listening experience, summarized by captions containing the thoughts of the subjects portrayed, whereas the image is intentionally viewed as the final outcome of a significant relationship-based process.

Reflecting a number of transcultural influences (with particular reference to De humani corporis fabrica, the first modern anatomy textbook by Andreas Vesalius, 1543), Adjovi observes and captures signs and formal patterns etched on people’s faces and on the walls of their mud-brick houses. The house therefore appears as the collective body on which the community impresses its mark.

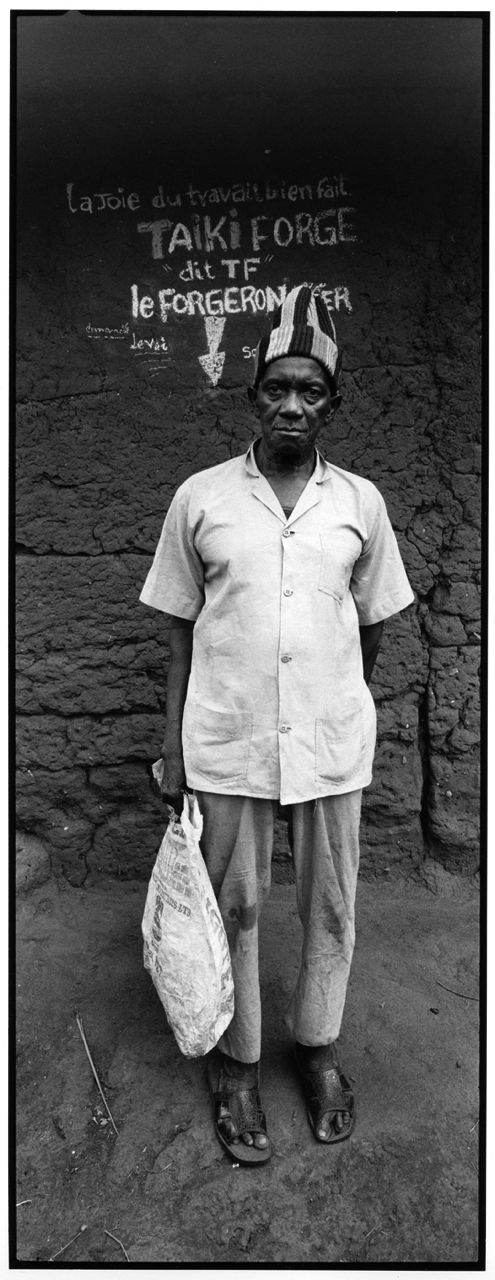

Photographer and traveller Jean-Jacques Moles also focuses on the interplay between collective and individual bodies in the series Aux Portes du Bénin.

We met him under the large paillote of the Institut Français, with a view on the full-sized prints of his black-and-white portraits located in the palm garden. He told us about the long correspondence between his wife Chantal, an Amnesty International activist, and Louis, a prisoner of conscience during the communist era. He talked about their friendship and frequent visits to the village of Adanhondjigon, a few kilometers of dirt road from the royal Abomey, where Louis returned after being released. Moles portrays his subjects at the doors of their homes, whose façades are often etched with popular or religious aphorisms.

Here, the individual body literally incarnates the body of tradition, but there is also an unsettling element in the scene that depends on his photographic technique. His analog pictures are actually taken with a panoramic camera positioned vertically. In his elegant portfolio of prints, featuring an evocative text by Beninese writer Florent Couao-Zotti, the white writings inscribed on the dark walls seem to be etched on the surface of the negative, this apparent gap between image and support suggesting an existential gap, a possible divergence between individual and collective identity.

Based in Porto Novo, French photographer Catherine Laurent focuses on empty buildings, obsessively portrayed in detail.

Built by freed slaves coming from Brazil, these amazing and eclectic houses combine Portuguese and French colonial architecture. Rotted by humidity and left in a state of decay and abandonment for decades, these ruins evoke a dream of equality, and perhaps of redemption, that the present reality seems to have shattered. The bushes and wild grass (known as herbes folles in French) on which Laurent rests her melancholic gaze seem to suggest another possible (although unlikely) ending.

Porto Novo is also home to Léonce Agbodjelou, the son of a well-known studio photographer in West Africa, whose work is exhibited in the most prestigious art galleries of London and New York. His Demoiselles de Porto Novo , showcased in Cotonou, is a post-colonial reinterpretation of an art nègre masterpiece.

Here, the ironic reference to Picasso, displaced in the interior of Agbodjelou’s house, is embodied in the female nude. Covering the models’ faces, the masks objectify their bodies, while also irradiating a mysterious and powerful energy.

Outside the garden of the Institut Français (the only public green space in Cotonou), the city –the most densely populated in Benin, with more than 700,000 inhabitants – swarms with bodies, especially young people. From dawn to dusk, as the torches of illegal gasoline vendors cast the green reflection of glass containers on the streets, all these bodies bustle around with objects, projects and memories: packed together on buses filled up to the roof, buzzing the streets like insects on roaring motorbike taxis, or walking on wobbly drain covers along the dusty roads.

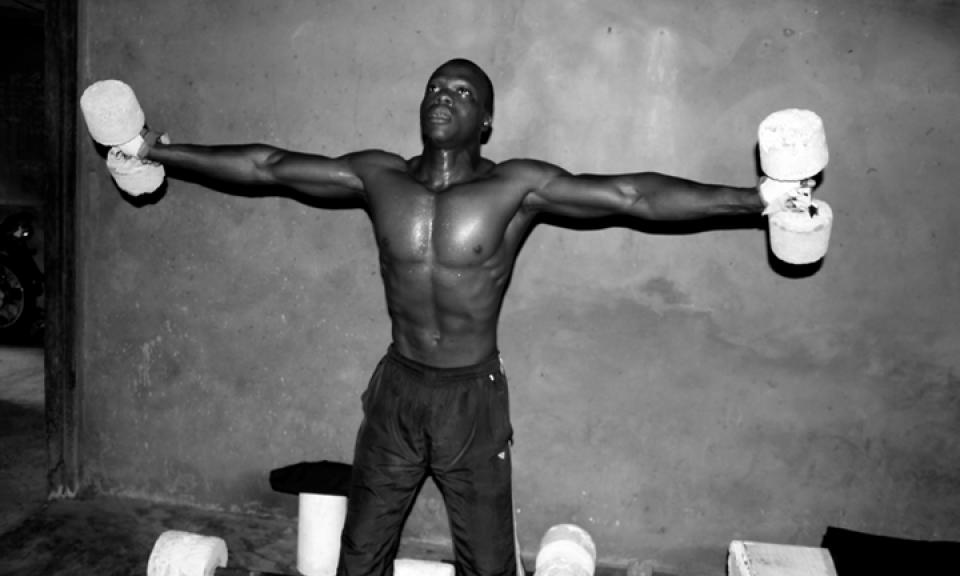

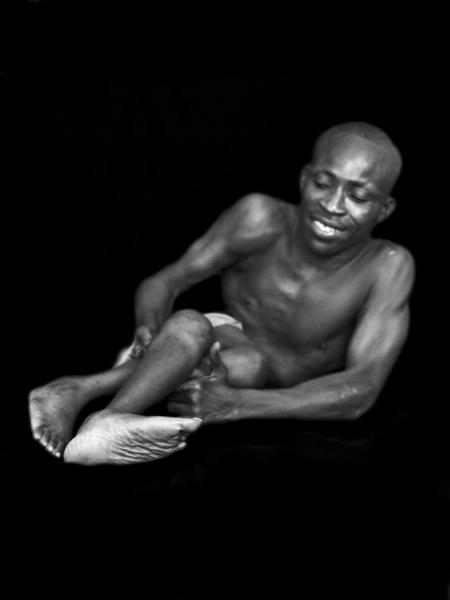

These bodies take center stage in the Beninese photography scene, which is very lively also thanks to other independent projects such as Redresseurs de Calavi by Ishola Akpo,

where the gym becomes a metaphor for justice, with a group of young people fighting against the spread of corruption and abuse; or the series by Sophie Negrier, another émigrée, where the bodies of the disabled begging at traffic lights are brought into a sort of gravity-free environment, artificially recreated through studio lights and backdrops, reminiscent of Bacon’s distorted figures and Matisse’s dances.

Marco Maggi teaches at Università della Svizzera italiana (USI) and is photography critic for “L’Indice dei libri del mese.”

Since 2011

Since 2011