“A gift is the evidence of an act, a symbolic gesture that is at once free and obligatory,” writes Katia Anguelova, curator of AtWork Dakar 2012. “Considered in terms of a give-and-take relationship, the work of art can therefore be regarded as a gift or a representation of a gift.” This is the central idea of AtWork, the educational format created by lettera27 and Simon Njami. Its key element is a workshop during which participants produce a personalized notebook, which they can choose to donate to lettera27, thus becoming part of AtWork Community.

The workshop that has recently taken place in Italy, in partnership with Fondazione Fotografia Modena, was entirely dedicated to the photographic image and was attended, among others, by the young Ivorian aspiring photographer Mohamed Keita. The notebooks produced during the workshop were displayed in an exhibition co-curated by the students at the Fondazione Fotografia Modena’s atelier in Via Giardini.

Drawing on Foucault’s idea of heterotopy, Simon Njami chose “heterochrony” as the main theme of the workshop, describing it as “a break with real-time that introduces multiple time-spaces from which it is possible to reconsider artistic practices and viewing experiences.”

The closing event of AtWork was the opening of the solo exhibition of South African photographer Santu Mofokeng (b. 1956, Johannesburg), winner of the International Photography Prize promoted by Fondazione Fotografia Modena in partnership with Sky Arte HD. The exhibition “A Silent Solitude (Photographs 1982-2011),” curated by Simon Njami, traces three decades of Mofokeng's life and career.

Santu Mofokeng started out as a street photographer in Soweto in the 1970s, while still a teenager. In 1981, he went on to work as a darkroom assistant at Beeld newspaper in Johannesburg, and then became a freelance photographer, working for the Chamber of Mines journals. In 1985 he joined the Afrapix collective, a photographers’ agency established in 1982 with the aim of contributing to the anti-apartheid struggle through social documentary photography. His work appeared in the Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian). In 1987 he began to work as a photographer for the New Nation, an alternative newspaper, documenting the rising discontent in the townships; the following year he joined the African Studies Institute at Wits University, focusing as a researcher on his photographic practice.

He soon began to realize that the messages he was trying to convey through his pictures, “however singular and different from others that came before, would always be overshadowed by the perceptions and assumptions about South Africa that viewers bring with them.” He therefore started reflecting on the distance between photographer and object of representation in the South African context.

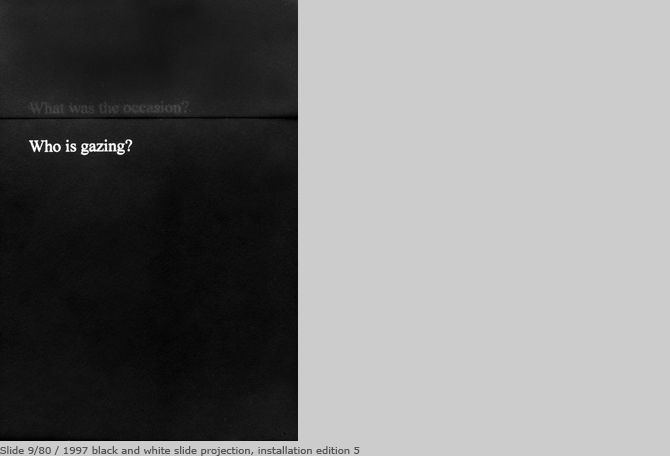

Starting with his first solo exhibition dedicated to townships, Mofokeng therefore “tried to take an active role rather than that of a mere voyeur,” as Simon Njami points out, “conceiving his work as an autobiography narrated by others,” a visual account able to evoke a particular moment, place, or silence, along with other moments, places and silences. This combination of different spaces and times – heterochronies, interruptions, breaks with real-time that introduce multiple time-spaces – can be understood as the sum of moments that make up a photograph: “The moment when the photographer sees the image, when he takes the shot, and when the viewer looks at it,” but also implies a multiple gaze able to transcend the image context, turning the subject into an archetype or idea.

All details and images are indeed dominated by the photographer’s ambiguous gaze, which questions the concept of “home,” namely “a fiction we create out of a need to belong.” All places and faces shown in his pictures are indicative of a specific context, but also produce a space of doubt in which they become a “living metaphor,” transcending the limits of the photographic medium. In this way, the subject turns into a “founder of discursivity” – namely, a discourse/gaze on the photographed reality; on what it provokes in the viewers, based on their own experiences; and on photography itself.

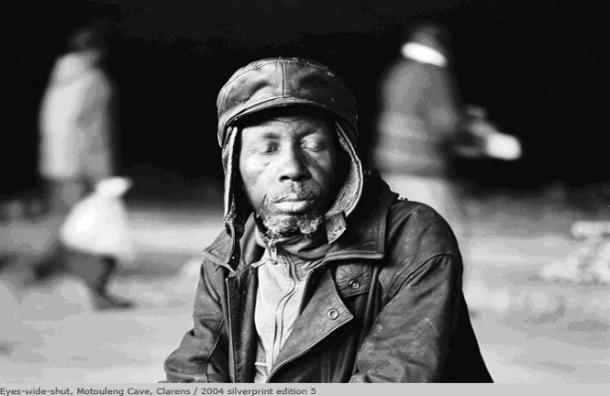

This combination of elements creates a picture that is impossible to forget. In Eyes-wide-shut, Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 2004 (Ishmael), there is something that goes beyond the mere reference, something indefinite and elusive. It is the picture of a man with a hat on his head and a shifty, almost resigned look on his face. His gaze is distant. As Simon Njami explains, it is Mofokeng’s brother Ishmael, suffering from AIDS, on a pilgrimage to the holy Motouleng Cave in Clarens, shortly before his death. Yet there is more to it than this.

His eyes seem closed, but this is a visual impression that requires confirmation. If you take a few steps closer to the image, you will come to a sudden revelation: Ishmael’s eyes are slightly veiled, but open. Here and now, in the space of a close-up vision, the imaginary line between the man’s and the viewer’s gaze becomes blurred. The shadow in Ishmael’s eyes does not suggest the presence of an absence, but evokes something immaterial that appears in all Mofokeng’s Chasing Shadows pictures: an invitation for the viewer to get involved in an aesthetic experience, an exhortation to move into the space of reality to fill the gap of paradox, as the eyes are only apparently closed, and the shadow is at once real and unreal.

“Come,” the image seems to say. “Come and get into my world.” That’s exactly what happens. However, in Mofokeng’s pictures, the “description” – as Foucault would have it – is not a form of reproduction but of deciphering. In each element of the picture, states Simon Njami, beyond the “description” it is actually possible to “find a universal space for inscription,” where the last word does not necessarily belong to the main subject of the discourse but involves each viewer. In this way, a landscape also evokes a different place, face, or shadow, the outskirts of a South African or Asian city.

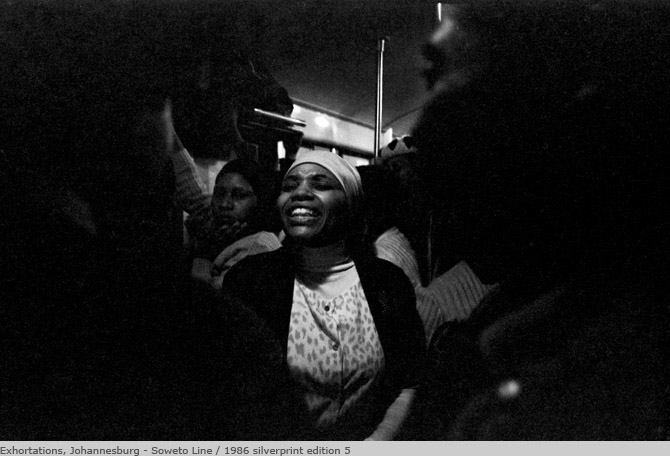

This is evident in the Train Church series (1986), a body of photographs about church services held on the overcrowded commuter trains running between Soweto and Johannesburg. Suspended between the beauty and heroism of vision, immersed in sounds and songs, the individuals captured in these pictures transform a fragment of time into a cathartic prayer, a hymn to survival, as indicated by the captions: Exhortations, Opening Song, and Supplication. Mofokeng, also travelling on the same train, shows the faces of men and women gripped in a sudden and bizarre religious ecstasy, with a combination of mystical beams of light and shadows making their bodies evanescent, suspended in a timeless atmosphere.

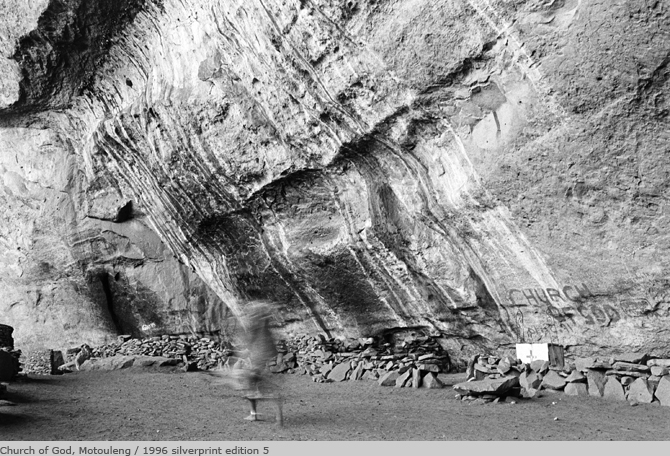

In Chasing Shadows (1996-2004), Mofokeng deals with the issue of spirituality from another perspective. Spanning nearly a decade, these pictures were taken in the caves of Motouleng, Manspopa and various pilgrimage sites in the Free State province of South Africa, worshipped as holy places by both Christian communities and the followers of other ancestral religions. The “shadows” are souls, entities, spirits, and energies that are part of the world. They evoke something that is both imaginary and real, blurring the line between sacred and profane, human and divine. In Church of God, the sacredness of the place becomes one with the “aura” of the individual, their invisible forces leaving tangible traces in the world.

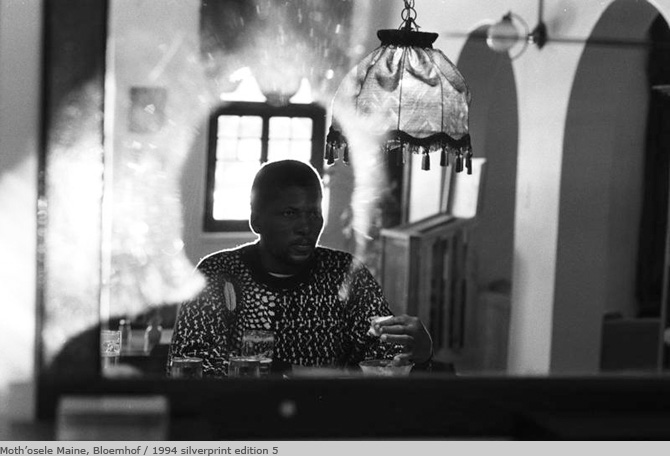

As Mofokeng points out, in South Africa, unlike in the European tradition, “shadow” indicates something real. Seriti – the word for “shadow” in sesotho, his mother tongue – does not just refer to the absence of light, but can mean anything from aura, presence, confidence, or dignity, also referring to the power to attract good luck and ward off evil forces and illness. This is evident in Rumours/The Bloemhof Portfolio (1988–1994), where the voices evoked by Mofokeng are translated into a photographic language. Bloemhof is a small town of the Transvaal region in South Africa, where Mofokeng documented the lives of tenant farmers, often referred to as “yokels”, and observed people’s excitement and fear on the eve of the first democratic elections in 1994, as emblematically shown in Moth’osele Maine. Here, a light seems to emerge from the shadow of the subject, overlapping his image and brightening the room, but it might as well be the photographer’s or the viewer’s reflection, a trace of their own gazes and expectations.

It is within this framework that Mofokeng’s visual journeys are inscribed, along with his attempts to give substance to South African landscapes of violence and tragedy. Here, the concept of seriti-shadow suggests a form of “remembrance,” namely – as Mofokeng states – a process through which forgotten memories come back to life. The body is the landscape on which the most relevant stories and myths in the construction of national identity are inscribed. In Vlakplaas (the infamous Apartheid detention and execution centre), the natural landscape is only ruined by the presence of a wire fence, a sign of the prison area as well as a metaphorical scar in the memory of the country; in a similar way, in the Robben Island triptych, only the corners of the wall separating the detention space from the outside world are visible.

With this awareness, Santu Mofokeng took a journey to the places of tragedy in Europe and Asia, with the aim of understanding the various strategies for coping with mourning and remembrance, from which he drew inspiration for his Trauma Landscapes (1989-2005). Here, the idea of seriti-shadow takes the form of a cognitive process that Mofokeng describes as follows: “What is not in the photograph is in the memory, in the mind,” something that the viewer can relate to, based on his/her own experience. Once again, by avoiding any spectacular representation of suffering, he makes memory-charged places even more ambiguous and capable of transcending borders and geographical distances: see the placid, tree-lined lake where the ashes of thousands of concentration camp inmates were thrown; or Auschwitz railway tracks, wrapped in the winter fog, seen from above and from a distance, almost with no emotional attachment.

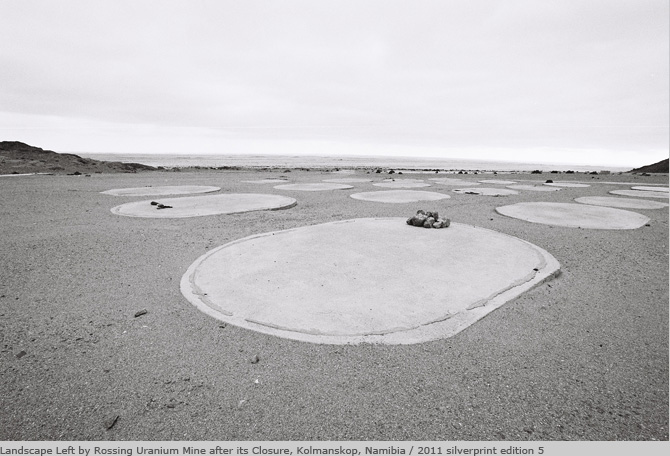

The same goes with the Poisoned Landscapes (2010-2011) and Climate Change (2007) series, which include pictures of disused mines and toxic waste sites, documenting the effects of climate change. Here, Mofokeng brings out what the viewer cannot easily glimpse, enhancing the ambiguity of the images and juxtaposing desolation and beauty, such as in Landscape Left by Rössing Uranium Mine, an ideal response to the Trauma Landscapes.

Drawing on Georges Didi-Huberman, Mofokeng’s photographs could be described as “figuring figures.” The automatism of the camera irremediably breaks with the idea of a “figured figure” (whereby nature is observed, imitated, and the result is a nice picture), replacing it with that of multiplicity. The image is therefore conceived as potency, as a potential part of a series, so the focus is not on the relation between a single image and the represented reality, but on the relation of each picture to the others, on the sequence. In this way, images overlap and refer to each other, thus enhancing their meaning and freeing themselves from the mere realism of representation.

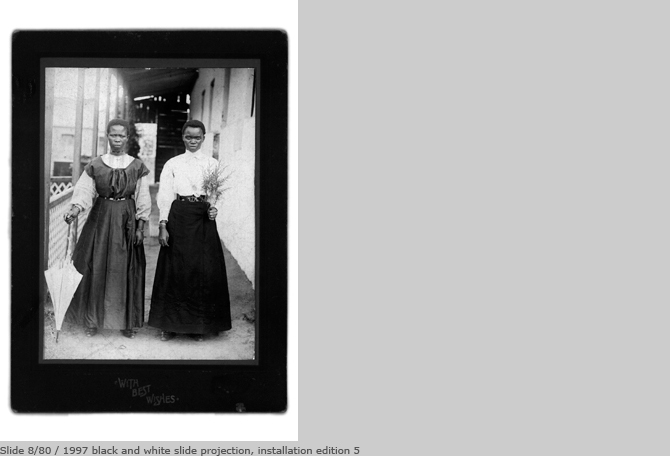

In The Black Photo Album/Look at Me: 1890-1950 (1997) series, inspired by old photographs found or purchased from family collections, Mofokeng “performs an almost antinomic research, suggesting that in every image there is something more important than the author’s subjective view,” states Njami. At the same time, this work can be regarded as a continuation of the Distorting Mirror/Township Imagined series, which is also related to another work by Mofokeng, entitled Township Billboards (1991-2004).

Mofokeng took a series of photographs dedicated to advertising billboards, a feature of township landscape traditionally used as a medium of communication between rulers and citizens. He describes them as rolling by “like the flipping pages in a book,” making explicit references to Apartheid ideology: see the OMO “whitening” washing powder advertisement; the ironic billboard depicting Robben Island – the place where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned – as a holiday destination; the slogan “Democracy is Forever”; and the criticism of visual pollution and advertising content.

All of this – as Mofokeng explains – forces him to question himself and his own potential: “Perhaps, I was looking for something that refuses to be photographed. I was only chasing shadows.” Was this the essence of collective consciousness? It is in this suspended space between doubt and ambiguity that Santu Mofokeng’s art takes place. What are these shadows? Where is the photographer’s eye? The answer is in the austere ambivalence of his pictures; doubt arises from the virtual space between the photograph and its caption: just a few words, and a gaze that envelops the viewers like a shadow as they face his opaque pictures. In this sense, Silent Solitude is not a synonym for silence but a gateway that allows us to delve into our own perceptions.

Translated by Laura Giacalone

“Santu Mofokeng. A Silent Solitude. Photographs 1982-2011” Exhibition, curated by Simon Njami, Foro Boario, Modena (Italy), March 6 to May 8, 2016.

Con il sostegno di ![]()

Since 2011

Since 2011