In Mogadishu, we children used to hang around together all the time. On holidays, we wandered from one place to another just for the sake of being together and setting out on adventures. However, there were rules in that apparent anarchy. The older kids made sure we always had the right amount of fear, just in case we came up with some silly ideas. That’s why my cousin told me about cannibals. She said there had been some ugly mugs hanging around lately… Rumour had it that a girl, taking a taxi home on her own, had accidentally bumped into a brutal murderer. Apparently, he was a normal guy but, as soon as they were alone in a deserted alley, his gentle eyes had turned flame red and he had pulled out a spit to feast on her flesh. I do not remember now whether the young girl actually survived or not, but just the idea of the poor girl trying to escape all alone was enough to hold us, little explorers, safely together against the perils of the world.

Numbis Scarf magazine launch @ Rich Mix.

Three decades have passed since then, but the sweet harmony, complicity and cheerfulness that accompanied our little adventures and marked our coming of age are still alive.

All our endeavours came from an intuition, from our close network of relationships, which allowed us to orientate ourselves while rambling from one place to another: an auntie would offer us some ice-cold orange juice when it was too hot, a cousin’s friend would secretly let us into the swimming pool of the Uruba Hotel, a girlfriend’s mom would give us some coconut sweets. Imagine a bunch of kids wandering through the narrow streets of a sleepy metropolis. When you move through the city’s maze-like neighbourhoods in groups, each corner, building, tree, street sign, or bench becomes part of everyone’s experience. Space and time fracture into a kaleidoscope of stories.

Almost a year ago, on the eve of the anniversary of Somali Independence Days of June 26 and July 1, I headed off to London to participate in a festival organised by Numbi Arts, a cultural organisation created by my friend Kinsi Abdulleh.

I was very excited to start my journey from Brussels Central Station and cross the Channel by ferry for the first time. We are now used to a sort of weird and induced ubiquity, hardly suited to our human need to internalise multiple time and space experiences. Six, seven, eight hours of bus travel would have left me the time to get out of the rhythms and occurrences of my everyday life. The festival was starting that night at the Rich Mix, a cultural space in the heart of East London.

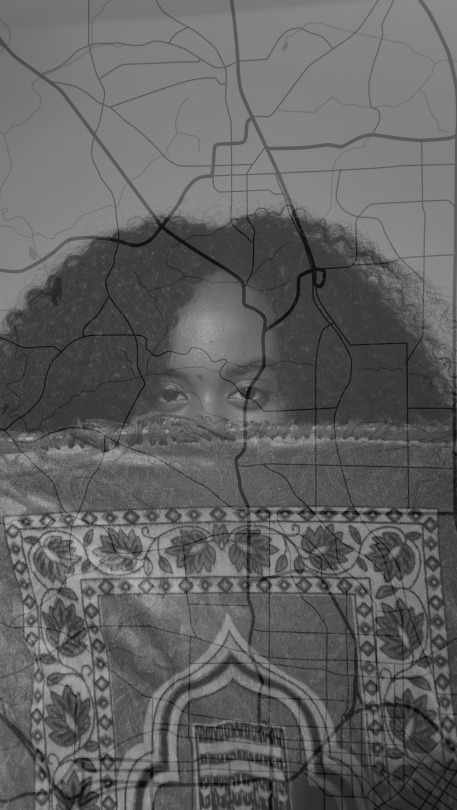

Photo by Nadyah Aissa.

Kinsi Abdulleh is a London-based visual artist and social activist. She spent her childhood and teenage years moving across Somalia, until the increasingly oppressive regime of Siyaad Barre forced her father to settle in Saudi Arabia. While recalling those nomadic years, Kinsi jokingly says that she was born in a suitcase, a hard-shell one. In those days, people were constantly on the move for political and economic reasons. Once in London, while studying at Farnham School of Art, now University for the Creative Arts (UCA), she started working at the Jazz Cafe of Newington Green, Islington. She told me her story while sitting on a park bench, not far from the place she was talking about. It was from that experience that she got the idea of setting up a creative space where artists could meet informally, collaborate, if they wished to, and exchange views. During the Sunday Jams, Nina Simone used to play the piano with a pair of sneakers on her feet; it was a clear example of how important it was to establish simple relationships based on mutual exchange, and share an ideal. The most urgent and debated issue back then was the struggle against Apartheid, but Kinsi was surprised to notice that many habitual visitors of the Jazz Cafe, coming from all over the world, knew all about Somalia. This made her realise that there was a connection between diasporic people, between all diasporas, their roots reaching out and intertwining with each other. In 1995, an important group of Somali poets and musicians, such as Hadrawi, Qarshi, Dacar, Dararamle and Hudeydi, came to the UK to participate in the World Circuit Festival, together with a number of Malian artists. On that occasion, Kinsi was asked to work as a facilitator and exhibit her Art works. It was an amazing experience, which allowed her to understand the complexity and universal significance of Somali poetry. In the same year, on the occasion of the exhibition Seven Stories About Modern Art in Africa at the Whitechapel Gallery, she came up with the idea of creating a cultural organisation named Kudu, inspired by a poem by Garriye. The verse fable by this Somali poet was about a king with antelope horns on his head; one day his servant took shelter under the trees and whispered this terrible secret into a hole in the ground. It is a hymn to freedom of speech, a condemnation of power, because “there was a time when such things could be openly said. Yes, there was a time when even the poor could be told the truth.” The experience with these poets was very important to Kinsi, prompting her to gather up her courage and launch her first exhibition. It was actually inconceivable to Somalis that she would call herself a “visual” artist, as there was no such thing in Somalia.

Photo by Nadyah Aissa.

People would ask her: “What do you do exactly? Are you a singer? Do you make dresses?” She wanted to stop justifying herself. She had some ideas and had to find the way to express them.

In those years, Somali women of different ages started gathering at a newly created cultural centre, called Sister Circle, to talk about the distorted representation of women in male-authored works of fiction and the creation of a community museum where they could share materials about Somalia, such as postcards, videos, objects, clothes, documents and photographs. The focus of their meetings was the purpose and preservation of the collected items.

According to Kinsi, life has a cyclical nature, and the most important events in her life seemed to follow a ten-year cyclical pattern. In 2005 she was in charge of organising a festival dedicated to Somalia’s pre-war cinema, theatre and music. Unfortunately, the festival was scheduled to begin on July 8, the day after London’s terror attacks. The Whitechapel Gallery, where the festival was supposed to take place, was located right next to the tube station. The coincidence was such a shock that all activities were suspended for a while. Violence seemed to keep plaguing the Somalis. In the end, the event was not cancelled. In spite of what had just happened, the theatre was crowded. It was amazing, considering that this place was only reachable by people from the neighbourhood or by car. People said they would rather go to the festival than listen to the news.

Photos from Numbi Heritage walk Intersectionality workshops and Numbi Rio exhibition.

Making the most of her previous experience with Kudu Arts, Kinsi decided to further develop her ideas by setting up Numbi, an organisation named after a traditional Somali dance where people let go of their inhibitions and try to restore communal harmony. Her aim was to promote a creative space where a new national identity could be envisioned, away from its tragic roots. We may not be ready yet – claims Kinsi – but we will always be able to share our stories. “The story I am sharing has the power to tell yours as well.” Numbi is also the name of a tree; it is only by spreading its seeds that the past can be connected with the future.

In the organisation of events, projects, and workshops, Kinsi was also assisted by Charity Njoki Mwaniki. They met a few years ago while Charity was conducting research for her Master’s Programme in Architecture, focusing on the relationship between space, identity and race in the UK. She was immediately attracted to Numbi, a platform able to gather a variety of artists for the creation of workshops, events, or publications, channelling their energies in pursuit of a final goal. Born in Kenya, Charity moved to London when she was 12 years old. She was particularly interested in the Somali community, not only because there were many Somalis in her country of origin, but also to counter their negative representation in the media. The years spent in Nakuru are still alive in her memory, and those places, landscapes and habits continue to affect her life. In her ideal world, time flows more slowly and there is a different approach to people and relationships, whereas in Europe time is a much more pragmatic and utilitarian concept.

Charity worked for many projects promoted by Numbi, particularly with Yenenesh Nigusse, an Ethiopian-Australian dancer based in London. During the performance I saw at the Rich Mix, Yenenesh, who also composed the music for the show, emerged from an amazing and delicate paper costume, which opened up to evoke a dream-like intertwining of cultures, historical periods and energies, producing an orchestra of sounds. Yenenesh was born in Ethiopia. When she was eight years old, she was adopted by an Australian family, together with her sister, and moved to Brisbane, Australia. Her adoptive mother wanted the two of them to maintain a connection with their past, so she got them an Ethiopian teacher to prevent them from forgetting their mother tongue. Thanks to the education received from her mother, Yenenesh developed a passion for various types of African dances. After many years, together with her sister, she came back to visit her hometown, Macallé. It was a journey they had long fantasised about, but which proved to be quite challenging emotionally. They even managed to recognise the home where they were born! In Australia, Yenenesh worked for Bemac, an organisation focusing on the combination of a variety of artistic forms, such as dance and poetry, and connecting people from different cultural backgrounds. By making the most of her personal experience, she started working as an educator to help adopted children establish a relationship between their past and current lives.

Photos from Numbi Heritage walk Intersectionality workshops and Numbi Rio exhibition.

The activities promoted by the Numbi Arts collective take place not only at the Rich Mix but also in a variety of places that reflect their spirit. One of our favourite places in London was the Iklectik Art Lab, a creative space open to workshops, lectures, screenings, music events and readings, described by its Director, Eduard Solaz, as a never-ending performance, a social installation, a place where people from different backgrounds meet and interact.

It was there, sitting at their outdoor tables among vegetable gardens and flowerbeds, that I listened to the story of poet Elmi Ali, one of the youngest members of Numbi.

Elmi was born in Nairobi to Somali parents in 1989. His father was an avid reader and, although their house had only two rooms, it was full of books, videotapes, and poems. Their home was also a place of reunion. When the civil war broke out, his mother jokingly said they should have received funds from the United Nations, considering the number of people they were giving shelter to. One room was for family members, while the other – filled with as many mattresses as they could find – was for the guests, whether transient or long-term. All these people then moved to other destinations, so wherever Elmi goes – he says ironically – there is a place for him to stay. Of those wandering years he still remembers the fear, because most of them had no papers and were afraid of being detected and expelled. The Somalis they gave shelter to came from all over the country, had different accents and many stories to tell. Elmi’s fascination for languages originated from his early childhood. He studied Swahili and English at school, and had been writing poems since he was 17 years old. In Manchester, where he currently lives, he is part of the Young Identity collective. He made his debut in 2009 at the Manchester Literature Festival. Elmi is also a talented performer: when declaiming his poems, he often refers to the Somali oral tradition, citing famous verses and revisiting their melodies.

In our wanderings, we used to stop at some quiet corner or a bench to write down a few words, take pictures of details, cut out images, or collect posters. Going from one neighbourhood to another on foot, by tube, or by bus, we were joined by other people, our group becoming smaller or bigger as we moved across the city.

There was Catherine, a British puppeteer from Trentino who worked as a researcher in Sierra Leone; Dunya, a French-Congolese yoga instructor and ticket inspector on high-speed trains; Judy, a Danish-Eritrean healer who used the sound of her voice to treat patients; Nadia, a drummer of Libyan origins who had spent nine years in Italy; SA, Yusra, Rashid, and many others. I have not mentioned everyone here, but the memory of each of them, of their eyes, is indelibly etched in those London walks. As we walked together, all stories seemed to intertwine with the landscape, marking the rhythm of our steps and our moments of rest, and made us feel close to each other, freed from solitude and disorientation.

In the last few months, after the Paris and Brussels attacks, I have long wondered about the widespread climate of fear that has enveloped the heavily guarded cities in which we are living. Unlike cannibals, which had the purpose of keeping us together, these new bogeymen have the opposite effect, generating mutual hostility and suspicion among people. What I wish to convey through these words is that the only antidote to fear is to keep on walking together, because only in this way we can empathise with the people around us and recognise that, as human beings, our destiny is inescapably bound with that of others.

Traduzione di Laura Giacalone.

With the support of ![]()

Since 2011

Since 2011