Giulio Paolini has often stated that in his work the end repeats the beginning, and that everything is there in the first sketch. Is this really the case? Why do artists so often represent their work as a perfect circle?

First, an answer to the second question. The narrative shape of artists’ biographies follow the eighteenth or nineteenth-century model imposed by the natural sciences. In the eyes of pre-Romantic and Romantic historians, events in individual lives and the entire history of art evolve in the same way as organisms, following the same steps. Birth, growth, maturity, decay (or decomposition) and death follow from one another ineluctably, at a given rhythm. Goethe believed a genius (if artists are geniuses) imitates nature without meaning to. The seed of creativity lies in the obscure evolutionary processes of the monad. It is not advisable to look too carefully into what is seen as being unintentional or involuntary. Everything, in this view, is self-produced, with no external contribution.

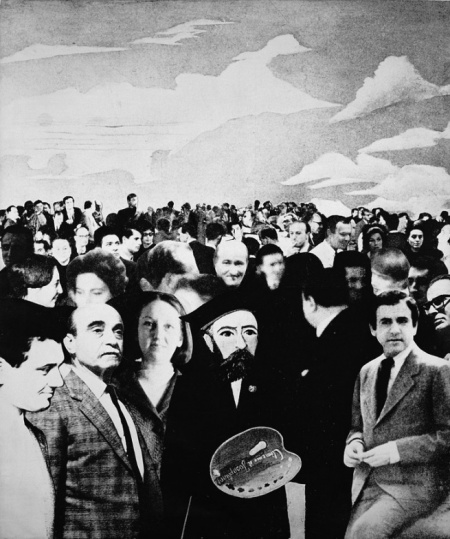

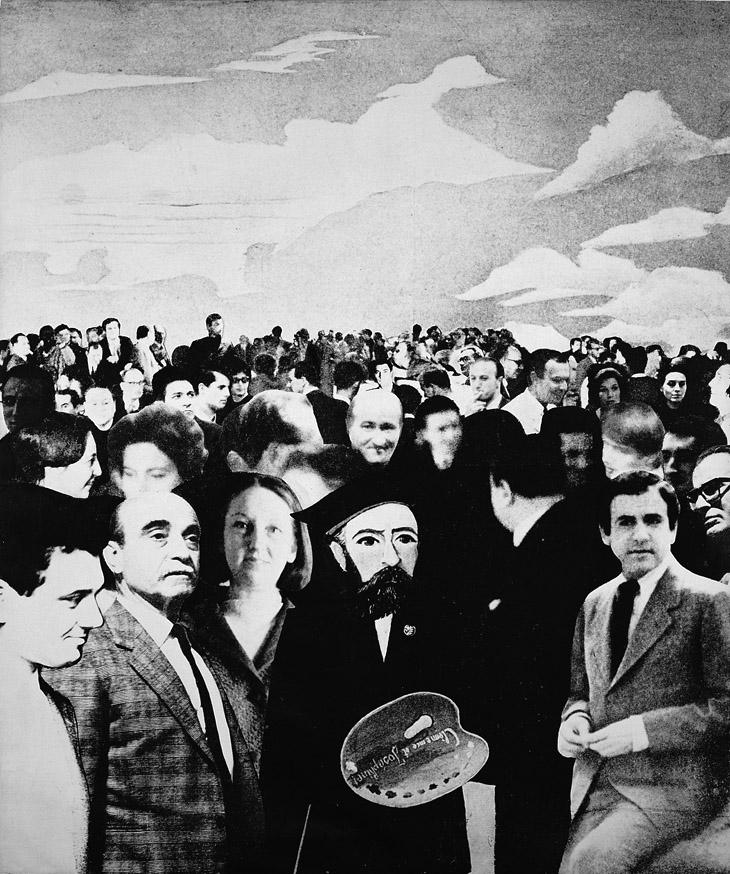

Giulio Paolini, Self-Portrait with Henri Rousseau le Douanier (1968)

Modernist autobiographies tend to reproduce Goethe’s organic myth of creativity. Klee’s diaries, which came out in German in 1957, and in 1960 in Italian (with a Preface by the art historian Giulio Carlo Argan) contain no reference to interruptions, cut-offs or dramatic shifts that we know affected the artist’s life. Klee gives an intimate and sequential account, which is imperturbable and totally coherent. It is important to note, however, that there is no banal reference to a linear form of “progress” as such. There is simply repetition and intensification. The model of reference is a living cell, an animal or a plant. An artist’s time is circular.

So what does this have to do with Giulio Paolini’s Self Portrait with Henri Rousseau le Douanier (1968)? A great deal. The painting represents a significant historical and artistic shift that has been neglected. But first we need to ask, why customs’ officers?

One of Paolini’s favorite themes is the adored (and mocked) painter: the artist as a naïf “idiot” or “saint” who knows no malice, guile or trickery. An artist that creates the world in the same way a leaf processes light or an animal rests and feeds.

On both sides of the custom’s officer, whose likeness is taken from Rousseau’s Moi-Même (1890) housed in the Národní Gallery in Prague, there are Lucio Fontana and Carla Lonzi. Surrounding the officer there are artists, critics, writers and intellectuals, gathered together like a merry band of brigands. There is no self-portrait of Paoletti in the picture. He dissolves his identity in a context of a network of affections, and pays homage to his interlocutors and mentors. The ego of the artist, he appears to suggest, is not hugely important. What matters in a painting are the layers of shared, community history.

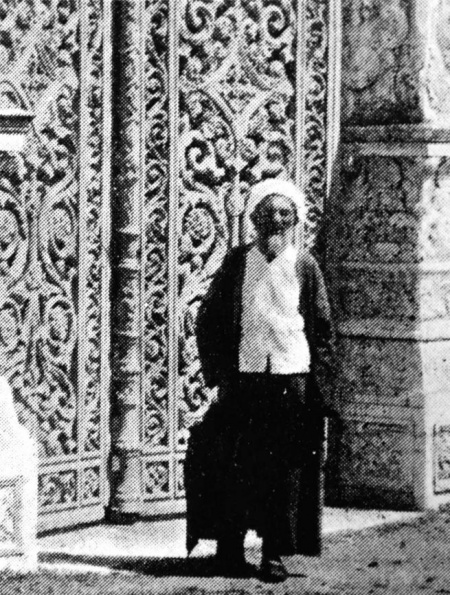

Henri Rosseau, Moi-Même (1890)

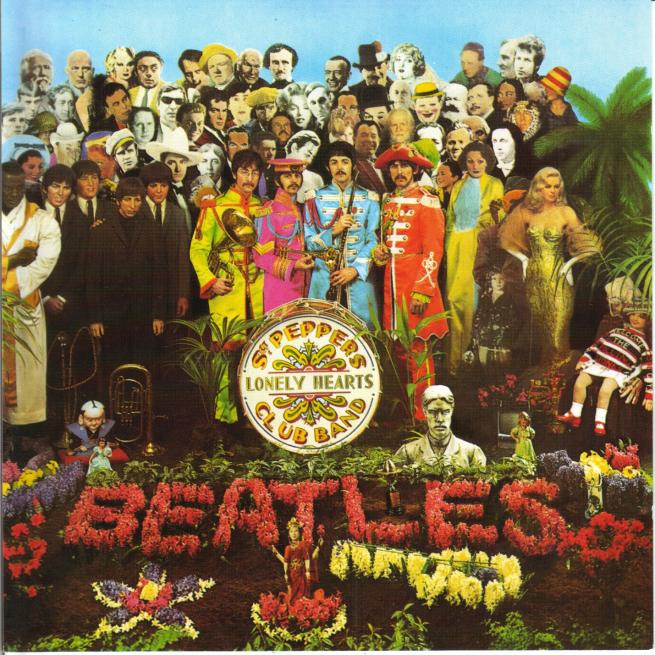

An illustrious forerunner in the community of self-portraits is the cover of the Beatles’ eighth album, Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band, which came out in 1967. The Liverpudlian musicians are surrounded in a similar manner by a multicolored crowd of friends, fans and followers. Introducing their latest LP to the general public, the Lonely Hearts in Sgt. Pepper’s Band place themselves under the tutelage of celebrities who are gaily transformed into protective deities. Designed by the British pop artist, Peter Blake in 1967, using the technique of photo-collage, the Beatles LP cover is both a group portrait and a playful family tree. Standing in support of the Band we can see Greta Garbo, Marlon Brando, Bob Dylan, Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, Lawrence of Arabia, and even Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. The community gathered together around the musicians is a paradoxical pantheon whose stage costumes lend them a burlesque quality. In figurative terms, Blake’s collage invents a witty new way - both scornful and respectful - to refer to tradition. A hippy “museum”, as it were.

The custom’s officer in Paolini’s work of art is not surrounded by Hollywood stars, popular comedians or rock singers. The crowd encircling Paolini’s alter ego is disciplined and composed. They are dressed in everyday clothes. There are academics and art critics, such as Argan and Maurizio Calvesi, as well as established artists. The world of fashion divas or showbiz personalities is very distant. There is a determinedly ordinary air to both the artists and the intellectuals. There are no bright colors or provocative hairstyles. And yet the lively group atmosphere is similar.

Peter Blake, Cover of Sgt. Pepper's..., 1967

The scene depicted by Paolini is participated and intensely social. It also has a national character, for a significant reason. The artistic and intellectual circles of Milan, Turin and Rome are represented against an early Renaissance Italian sky in the background – the same sky Rousseau used in Moi-Même – in what must be a deliberate citation of the previous work. The people are talking among themselves, and smile at one another. They look like they are part of a community that is untroubled by jealousy, competition, anxiety, or division. This idyllic community was never to return in Paolini’s work. There were other fictional self-portraits, Paolini dressed as Poussin, for example, or as an old Oriental, but they are always out of context and standing alone. Contemporary Italy, even in the limited sense of an artistic or intellectual identity, ceased being a community, home, or ‘fatherland’ for the artist.

There is a cut-off in the artist’s life, despite his denial. There is a before and after that are not connected. There is a shift that is not just formal between the self-portrait in 1968 and the plaster casts from antique statues that Paolini devoted the next ten years of his life to. By adopting an archeological motif he expressed the loss – or, at least, the different context he was working in – in a plastic form.

The small domain of the Italian art world in the decade of the economic boom, a tight network of intimate or elective affinities –gathered around the Rousseau figure in the painting – evaporates at the end of the decade. The internationalization of the art market imposed a kind of conformism and led to unscrupulous behavior in some artists. There was no longer room for ‘polite’ relations, as Lonzi’s refusal to continue her career as a critic shows. The mobilization of the country in the crucial years of 1968-69 led some contemporaries, such as Pistoletto and Gilardi, to reject the world of esthetics altogether and take on a more socially-minded practice. The ideological battle was reproduced even in Paolini’s innermost circles and created some lasting split-ups. In the midst of the Arte Povera movement, the politically-minded artists opposed what they called the “formalists”, including Paolini.

Giulio Paolini, Self-Portrait, 1969

Thus, in my view, Paolini’s use of plaster calques modelled from antiquity during the 1970s was not necessarily a product of early New Dada concrete art from the 1960s, such as Disegno geometrico. Nor was it the result of his photographic experimentation from the second half of the decade, such as the Self-Portrait with Henri Rousseau le Douanier. On the contrary, the ‘neo-classical’ artist the anachronistic school modelled themselves on was very different from the versatile investigator of materials and techniques, or from the artist-connoisseur who paid homage in black and white to Renaissance and Baroque masters.

From 1969-1970, Paolini chose to abstain from industrial techniques or materials (such as photography) and to play the non-contemporary card. The links between art and society, as well as between esthetics and politics, suffocated him. He proposed revealing the mystery of a work of art by adopting archeological fragments as (de-contextualized) metaphors of our “origins”.

In Paolini’s view, art had nothing to do with the rhetoric of political engagement cited by Germano Celant in the texts he used to launch the Arte Povera movement. Nor did it have any connection to the ‘esthetics of a grocer’ (as Boetti put it) which characterized the pauperist installations of 1967 and 1968. Art was linked to a historical and artistic collective memory, to individual ‘Liberty’ (the title of the second work dedicated to the custom’s officer), and to the exploration of what we might call (with Yves Klein) the “immaterial”.

Since 2011

Since 2011