In these days of decapitations, tragic exoduses, impaled effigies, and new epidemics, media forums and the gurus of geopolitics lament the fact that western civilization is on its way back to a period that could be defined as the ‘New Middle Ages’. The definition was created in the last century by the Russian Philosopher, Nikolay Berdyaev, in the context of the First World War, published in Russian in a book by the same name in 1924. (The English version was entitled, ‘The End of Our Time’, Sheed and Ward, 1933). The same label was also commonly applied to the period of the oil price shocks and energy crises of the 1970s. At that time, a fascinating debate developed in the art world along the same lines, claiming that there had been a marked return to the past in the visual arts.

Before embarking on our virtual tour of these art works, however, a premise is necessary. This can be summed up in the title of the piece by Maurizio Nannucci: “All Art Has Been Contemporary”. According to this thesis, any work of art from the past is also part of our present. At the same time it interacts with our view of what is contemporary. Philosophers, moreover, have cast doubt on the existence of these categories of time. When is the present the present, and how long does it stay present? It is impossible to say. The present is not measurable and it is undeniably made up of pieces of the past and glimpses of the future. Furthermore, if there is no such thing as the present, what does the term ‘contemporary’ mean? Where do the confines of contemporaneity lie?

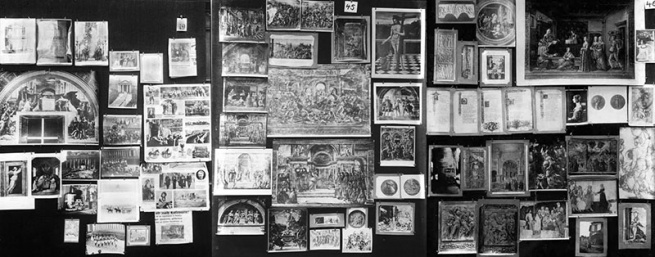

The twentieth century crisis of the idea of progress, which had driven so much of nineteenth century thought, gave artists the freedom to dig up relics and artifacts from the past. These inspired them to create works of art based on the concepts of contamination and citation. Forms from the past, as the art historian Aby Warburg pointed out, were filled with symbolic or iconic meanings which return to mind and stimulate our imagination through the emotional hard wiring of memory in a cyclical fashion.

Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne

Contemplate the Ancient

Ernst Howard, a renowned expert in the culture of antiquity, saw the rebirth of a taste for classical art as a “rhythmic form” of European cultural history. Greek or Roman antiquity, in every incarnation, reflects a project of the day, with its own ‘contemporary’ content, coordinates and implications. During the twentieth century, classical art was used by totalitarian regimes as a container for values and forms that were manipulated, distorted and simplified in order to lay claim to a presumed superiority of one race or culture over another. Similarly, but with a completely different aim, classicism was debated as an decontextualized icon by the avant-garde movement. Man Ray trained at a time when technical and pragmatic issues overrode questions of history or identity. In his photography, Milo’s Venus - often the subject of his photographs and assemblages – was merely a symbol of classical sculpture and, more generally, a prop representing the western artistic past. His ‘Venus Restored’, part of the Schwarz collection, featured a plaster cast Venus brutally trussed up in rough rope. Erotic allusions aside, this representation shows the the avant-garde annulment of history. The contrast between lowly materials and artistic perfection in classical sculpture was mimicked by the neo-avant-garde in Michelangelo Pistoletto’s ‘Venus of the Rags’ (Tate Modern, London). While Man Ray represented new versions of antiquity in a playful vein, Pistoletto’s ‘Venus of the Rags’ is tragically monumental. Venus turns away from the viewer: a representation of a crisis in the ideal transmission of cultural tradition. In the 1970s, and still today, the idea is challenged constantly. The rags Venus contemplates as she denies us her beauty represent the real world, diversity, and cultural contamination.

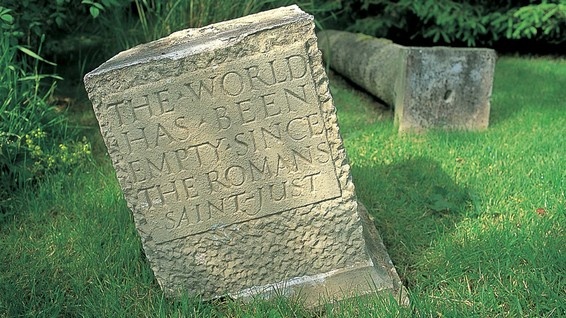

Other contemporary artists have considered classical art as the “lyrical soul of the modern” (Monti). The Romantic idea of antiquity has been revisited. Its aristocratic distance from the real world, the poetic ideal represented by ruins, and the tragic awareness that the cradle of civilization is no longer with us was important for the Greek artist, Janis Kounellis, for example. Ian Hamilton Finlay likewise filled his Scottish garden, which he called Little Sparta, with marble slabs engraved with texts in Roman capital letters.

Now that the classics of Greek and Latin history and literature are studied so little, except in rarefied academic circles, there is an increase in the use of citations from Antiquity. Decontextualized fragments are put together again in random fashion, producing a flattened and unambiguous image of classical art as perfection, balance, and measure, when its essence lies rather in its diversity and multiplicity of form.

Rediscovering these last vestiges has made it even more imperative that ancient history be studied again. The history of antiquity is relevant today because, as the Italian art critic, Salvatore Settis, has pointed out, “The Greek and Roman Classic Age could be seen as a far-reaching experiment in economic and cultural globalization […] which gives us a privileged insight not only into its early stages but also into the mechanisms of its decline and collapse.” As Umberto Eco put it, while antiquity is contemplated, copied and cited by contemporary artists, the Middle Ages are continuously re-created and re-experienced. We visit ancient monuments but we don’t live inside them, whereas we live in medieval cities and buildings, and medieval churches are still in use daily.

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Little Sparta Empty Since the Romans

Living the Medieval Age

Are there any real affinities between today and the Middle Ages? This question is increasingly relevant. As I said before, it was posed with urgency by cultural historians during the oil price shocks in the 1970s, when the western world was caught in the reverberations of the Revolution in Iran and the First Gulf War. At that time, Umberto Eco linked the contemporary climate to the Middle Ages, comparing the global context to the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Just as in the 1970s the centrality of the United States was called into question (and just as today we are experiencing the consequences of the decline of American economic supremacy), so “the collapse of a general Pax creates a crisis of security, diverse civilizations come into conflict, and the image of a new man is slowly created.” Other affinities include an extraordinary intellectual fervor, and the clash between tradition and diversity. Not to mention the contamination of a sense of insecurity. The authority of the past – whether it is cultural or political – allows society to trace common roots that are the basis for a common identity, and supports society as it considers its future. We all feel, as Bernard of Chartres did back in the twelfth century, like “dwarves perching on the shoulders of giants”.

There is no shortage of reflection on this subject, even with reference to the visual arts. Examples of twentieth century studies include Meyer Shapiro, Leo Steinberg, Lionello Venturi, Henri Focillon, and Eugenio Battisti. All these researchers found links and contaminations between the Middle Ages and contemporary art, and thus drew new borders between the two epochs. Today Aby Warburg’s habit of connecting time, place and knowledge has become highly relevant. When he considered Arab, Medieval and Late Medieval material as a composite, he managed to demonstrate that in order to reconstruct a history of form it was necessary to cast his net of primary sources far wider than merely the classics.

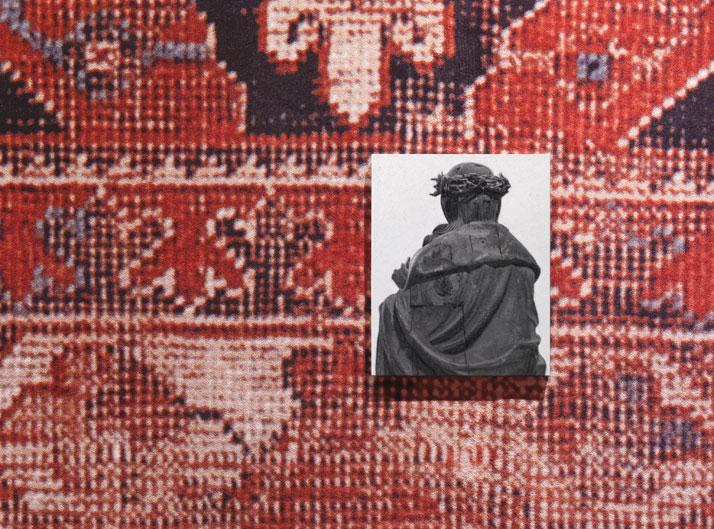

Recently, both post-disciplinary theory (I refer in particular to Alexander Nagel’s ‘Medieval Modern’, to which I owe much of this article) and historical-artistic practice has shown the validity and the persistence of these premises. The modernist critique of museums as institutions, of academic endeavor, of paintings on easels, and of artists as unique creators triggered a strong sense of connection with medieval art which preceded even these vey institutions and modes of artistic production. Critics and artists saw medieval churches and chapels with new eyes. They admired their mises en scène, and appreciated the fact that the objects and paintings in these places were not self-sufficient but rather interacted with one another. In this sense, they were pre-cursors of site-specific art works which aimed to grab the attention of viewers in the same way medieval frescoes did. An example of this was the appreciation for Giotto’s work in the Cappella degli Scrovegni on the part of Heiner Friedrich, founder of the Dia Art Foundation. In his view, and in Nagel’s, in medieval chapels the various parts of the whole resound together, creating a totalizing and harmonic religious experience in the viewer. A sense of total immersion in a site, with its long figurative carpet, and the consequent sense of bewilderment, has been replicated in Rudolf Stingel’s installations. In his most recent work, at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, the museum site was completely covered in a reproduction of an oriental carpet, and the walls – like the side chapels in a church – were decorated with mostly black and white reproductions of medieval sculptures.

In recent decades, various exhibitions have attempted provocative juxtapositions between medieval and contemporary art. Medievalists have also analyzed the resonance on contemporary artists of artistic paradigms that were rife in the Middle Ages, such as reliquaries, altars, Byzantine icons, ritual practices, and so on. An example could be the Reliquary of St Andrew’s Sandal in the Cathedral of Treviri, commissioned in c. 980 by one of the great art patrons of the early Middle Ages, Bishop Egbert. Using terms relating to contemporary art, one could call it an ‘assemblage’ (of assorted styles and materials), or an example of ‘ready-made’ art (because it contains already existing objects, such as St Andrew’s sandal and other reliquaries). Contemporary artists recognize certain affinities with the strategies used to construct reliquaries. Indeed, the piece of art that is quintessentially iconic in the new millennium – a nineteenth century skull covered in platinum and studded with diamonds entitled ‘For the Love of God’ (Damien Hirst, 2007) – explicitly cites reliquaries in its symbolic message: contemporary devotion to the God of Money.

As if to confirm the relevance of these issues, the last Venice biennale was designed by its curator, Massimiliano Gioni, as an exhibition on the quest for knowledge in baroque and medieval times. Encyclopedias, where stories, myths and legends are related according to an idea of knowledge acquisition based on connections and associations, are a far cry from the enlightenment mentality which tried to categorize the world. The video installation that won the Leone d’argento, ‘Grosse Fatigue’, by the French artist, Camille Henrot, is emblematic of these critical and poetic preferences. It re-tells various myths concerning the birth and evolution of the Universe using materials from the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. Today, as in the Middle Ages, there are ongoing attempts to organize the excessive amount of information and images produced by cultural clashes that have surpassed their cultural, geographical or temporal confines. Reflecting on the “composition and collage that erudite culture today makes of the detritus of past culture”, Umberto Eco claims that if we look at, for example, one of Cornell’s magic boxes, an accumulation of Armand’s possessions, a useless Munari machine, we will see “a landscape that has nothing to do with Raffaello or Canova, but a great deal to do with the medieval esthetic.”

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue, 2013

Mosaic: a Medieval Card in the Contemporary

Mosaics have also played a significant role in the debate on contemporary borrowings from the Middle Ages. In two 1967 photographs, the famous Canadian sociologist, Marshall McLuhan, is portrayed next to a book open at a page showing the mosaics in the Hagia Sophia Museum in Istanbul. Of course this was not a random choice. In McLuhan’s view, in fact, mosaics were the medieval medium par excellence. As he points out repeatedly in his book, ‘The Gutenberg Galaxy, the Making of Typographic Man’ (Toronto, 1962), mosaics were both a tool and a metaphor for understanding contemporary communications. The book itself, the author claimed, was built in a “mosaic-like structure”, with 107 mosaic-like pieces that made up a mosaic-like discourse using heterogenous arguments referring to many different periods. He also used glosses to comment on his texts, which he called “illuminations” in a re-visitation of the techniques used in illuminated manuscripts.

McLuhan’s basic premise in his book was that since the invention of the printing press and movable typeface, the western world has operated an ongoing and increasing “segmentation of actions and functions” and the “principle of visual quantification” has been challenged. The “three-dimensional world” of “pictorial space”, in his view, was an abstract illusion based on this “segmentation” or separation of visual perception from the other senses. By contrast, as McLuhan pointed out, the scholastic method prevalent in the Middle Ages was mosaic-like in that it dealt with different aspects and various levels of meaning simultaneously.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Cezanne painted, as he himself said, as if objects were in his hand rather than viewed from afar. Painters started to abandon Renaissance perspective techniques and attempted new styles, which allowed them to represent a multiplicity of points of view. Proust and Joyce, in the field of literature, applied the same method, creating multi-layered simultaneous views of different subjects at different points in time. McLuhan defined them as the masters of “tactile medieval mosaic”. Mosaics were able to interpret the spirit of modernity because they were vehicles of recognizable representational strategies and values, as two great figures of contemporary culture – Kandinsky and Pasolini – show.

At the end of the nineteenth century, an anti-positivist sentiment shook European culture, condemning both materialism and representational paradigms from the past. At the same time, the discovery that atoms could be split, with all its implications, opened up new avenues for art. Artists reformulated the concepts of space, time and matter and tended towards creations which represented simultaneity and multidimensionality – for which mosaics were both a precedent and an inspiration. In 1912, Kandinsky chose the Ravenna San Vitale mosaic of Theodora’s procession as the main illustration for his essay on spirituality in art. According to this artist and theoretician, who was Greek-Orthodox and an expert in religious icons, contemporary art had identical resonances to the art of the past. Art, in his view, gives us the tools for achieving a spiritual dimension and overcoming materialism.

More than sixty years of figurative revolutions later, modern art was once again compared to the Ravenna mosaics. In 1975, in fact, Pasolini wrote in his introduction to the Andy Warhol exhibition in Ferrara: “I’m looking at a series of Warhol’s prints. My impression is that I am gazing on a Ravenna affresco (sic.) where the isocephaly of the figures is highlighted by the fact they are all facing me and that they are repeated to the extent that they lose their identity. As with identical twins, you can only recognize them from the color of their robes. The nave of the cathedral Warhol has built and then knocked down, breaking the figures up into repeated, cut-outs of the same height, is effectively Byzantine. It would seem that the quality of American life is equivalent to the authoritarian sacrality of official early Christian pictorial art: that is, it provides a metaphysical model for every possible living person. There are no alternatives to these models, only variations.”

In conclusion, in order to interpret contemporary art effectively, the basic requisites of medieval art and of mosaics have returned to the fore. These requisites, which have now become highly contemporary, are first, that a single recognized author is not necessary, second, that any work of art can be serialized or replicated, and, finally, that there is a signifying value to the decorative aspect of the work of art.

Since 2011

Since 2011