’s-Hertoghenbosch, 9 August 1516.

The funeral service for the painter Jheronimus Bosch is held in the church of St. John. The mourners gather in the new chapel of the Brotherhood of Our Lady (Lieve Vrouwe Broederschap), of which Bosch is a “sworn member”. The Requiem mass is organised by the brotherhood, who cover the costs, as was the custom. The perfectly preserved book of accounts is a precious artefact: from the expenses accrued we can deduce that this is the final tribute to an important and highly revered man. He would have been around 65 years old, although the date of his birth is unknown (1450-55).

Ten years ago, to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of the artist, Charles de Mooij, director of the Noordbrabants Museum, began work on an ambitious project: to bring the entire body of the surviving work of the most imaginative Netherlandish artist back to ‘s Hertoghenbosh, the city where Jheronimus Bosch was born, for the largest retrospective ever dedicated to him.

Bosch’s work is spread around the world: 25 museums, some giants like the Louvre, Metropolitan and Prado, in ten different countries. And Charles de Mooij, from the Noordbrabants Museum, doesn’t have a single painting to offer in return. But in October 2007, with the Bosch expert and professor of art history at Nijmegen, Jos Koldeweij, he presents his project: Bosch Visions. The idea is to launch a large-scale research program that involves every single Museum, without exception, in a new venture, so that the full corpus could be looked at again, studied, restored, and preserved with the help of the most advanced techniques. The creation of a research and conservation project focused on Bosch paved the way for the exhibition. This is how the Bosch Research and Conservation Project was born, an international team of researchers guided by Jos Koldeweij and Matthijs Ilsink (together with the Stichting Hieronymus Bosch 500 foundation and the Radboud Universiteit in Nijmegen). The result is, to say the least, extraordinary. By 2013, the BRCP had already worked in 20 museums, from Paris to New York, Madrid and Venice. The works preserved in Venice (at the Accademia and Palazzo Grimani) for instance, which, after those preserved at the Museo Nacional del Prado, constitute the largest corpus in the world, have been under the lens of research and restoration: Bosch in Venice. Thanks to this restoration, the Heremit Saints Triptych, the Saint Wilgefortis Triptych, and the Visions of the Hereafter were returned to a condition in which they could travel, and are now resplendent at the celebrations of the museum of the prettiest city in North Brabant, next to the other works, reunited almost in their entirety.

Jheronimus Bosch, Visions of the Hereafter, ca. 1505-15, Venice, Museo di Palazzo Grimani. Photo Rik Klein Gotink and image processing Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

The Bosch Research and Conservation Project team conducts research on the Saint Wilgefortis Triptych

“Visions of genius”

On display are 20 of the 25 surviving paintings and 19 of the 20 drawings known. 12 of the restored works are on display here for the first time. The exhibition is articulated in six themes: The pilgrimage of Life, Bosch in ’s-Hertogenbosch, The Life of Christ, Saints, The End of Time. One room is dedicated to Bosch as Draughtsman; it is unlikely that all these precious sheets will ever be together again. Infernal Landscape, a drawing that has recently been attributed to the artist, has never been on public display before. It’s a homecoming that really set the gears in motion. Exceptional loans, like The Haywain, a tryptic that hadn’t left Madrid in 450 years; The Garden of Earthly Delights, on the other hand, never will it leave the Prado. But the curators found a way by resorting to a private collection: an incredible copy of the central panel of the work, painted between 1539 and 1560 by a follower of Bosch. And it is this matter of the copies and followers that is one of the most pronounced areas of the research of the BRCP. The exhibition comprises also seven panels from his studio or of significant pupils, spaced out among those now attributed to him scientifically: and yet the refined visions of the master are distinguished from the imitations. Books, prints and a series of rare objects of the period immerse us in the historical and cultural context in which Bosch’s works were produced.

Bosch in ’s-Hertogenbosch, splendid isolation?

Born around 1450, one of the first mentions of his name dates back to 1474, cited as “Jeroen known as Joen", or Jheronimus, which is the local form of the Latin for Saint Jerome (Hieronymus). In the archives, the family is always referred to with the surname “Van Aken", that is from Aachen. In reality, the grandfather, the painter Jan van Aken, moved the family to ’s-Hertogenbosh (“The Duke’s Forest”) around 1426 from Nijmegen, where they had lived for generations. A family of painters and artisans: the grandfather, the father Antonius, and three uncles were artists by profession and it is believed that, like his two brothers, Jheronimus took his first steps in the family workshop. We don’t know anything about his travels or studies, but we can presume that he would have attended the Latin school, unlike most of his peers. We know that around 1480 he married Aleid, daughter of the wealthy and cultured Van de Meervenne family. Bosch and his wife lived in the seventh house from the right (near the light blue house), on the North side of the city’s market square. On the east side, which was less elegant, stood the house where he had grown up, and the family workshop. We see a painting by an anonymous artist, The Cloth Market (ca. 1530), the only painting that documents the commerce that flourished towards the end of the 15th century, when the city saw an economic boom following a period of war, famine and plagues (1436-1442). Silversmiths, sculptors and printers worked busily away. The atmosphere in the Market Square, the beating heart of the city, has not changed much and is still as bustling today, in its characteristic triangular shape.

Anonymous, The draper's market in 's-Hertogenbosch (and detail), ca. 1530, Den Bosch, Het Noordbrabants Museum

A few years after the wedding, the family prodigy entered the Brotherhood of our Lady (1487-88), an important religious association. This represented a significant step up the social ladder, accomplished thanks to his skill as a painter rather than his social status, and confirmation of his prestige. Perhaps as a sign of recognition, for the new column of the altar in the brotherhood’s chapel, he produced Saint John on Patmos (and Saint John the Baptist, the two patrons of the church), a work in which we see his first known signature, painted in gothic letters. At that time in Holland, very few artists signed their work: only Jan van Eyck, who came sixty years before him, signed with the same frequency.

His creative mind is full of refined surprises: we have what is believed to be a self-portrait, a fantastical creature, discrete an in grey, with tiny glasses on the ridge of its nose as it looks towards a horizon unknown to us, and its sadness can’t hold its tongue; it’s in the bottom right, right above the signature, Jheronimus bosch. The toponym, Bosch, thus distinguishes himself from the rest of the family, Van Aken.

Jheronimus Bosch, Saint John on Patmos, ca. 1490-95, Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. Photo Rik Klein Gotink/Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

At that time, ’s-Hertogenbosh was one of the four capitals of the Duchy of Brabant, as early as 1185 the Duke Henry I had awarded it the title of city with its associated commercial priviledges. In artistic terms, however, it was somewhat behind. Splendid isolation? Perhaps yes, since the work of Bosch and his workshop seems unaffected by the trends of the vibrant cultural centres like Antwerp, Bruges, Venice, Rome or Paris. But his education in the humanities and the incredible imagination of the painter who ”signs himself Bosch”, as we read in some documents, allowed him to develop a brand new visual language, which soon attracted the attention of the princes, nobility and intellectuals of his time, leading to important commissions (the most significant of which was for Philip the Fair in 1504 for a Last Judgement): fantastical imagery that has spawned a swathe of imitators and entire movements.

Today we count not more than twenty five panels and triptychs, and around twenty drawings attributed to him with certainty, all produced between 1480 and his death in the summer of 1516. But as a member of a family of artists, he almost certainly began painting at a very young age, and this leads us to presume that much of his work has been lost. What has survived appears to us in themes dear to the painter. Thus we see how Bosch illustrates The Life of Christ in a moving and lyrical way, with for example, an extraordinary Christ Child with the walking frame – and on the other side of the same panel, Christ Carrying the Cross (Vienna). This left panel (which has just been restored) is all that remains of a lost triptych.

Hieronymus Bosch, Christ Child – Carrying the Cross, ca. 1490–1510. Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldegalerie © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Gemäldergalerie, KHM-Museumsverband, Wenen

On the outside, a child with his toy windmill takes his first steps on the path of life that will see him, on the inside, carry the cross. This was his destiny. The image is specular, the pinwheel and cross occupy the same visual space. Then we come across the example of the Saints, the cult of which was very important, with, among others, a Saint Jerome at Prayer (his patron saint) surrounded by a landscape that is credible and incredible at the same time, and The Temptation of Saint Anthony (Kansas City, The Nelson-Atkins Museum) a fragment which the researchers have for the first time included in the autograph oeuvre of the master.

The tension rises with the start and the end of the world in flaming polyptychs presented in the section The End of Time, with The Last Judgement (Bruges) where you can spend hours admiring an ordered chaos of characters and inventions while a sky of fire seems to burst forth from the painting; the Visions of Hereafter (Venice) is a lyrical synthesis of a life of a visionary painter between heaven and hell. But his innovative mind has also created complex works based on everyday life, to which the wonderful section that opens the exhibition, The Pilgrimage of Life, is dedicated: it is the story of all men.

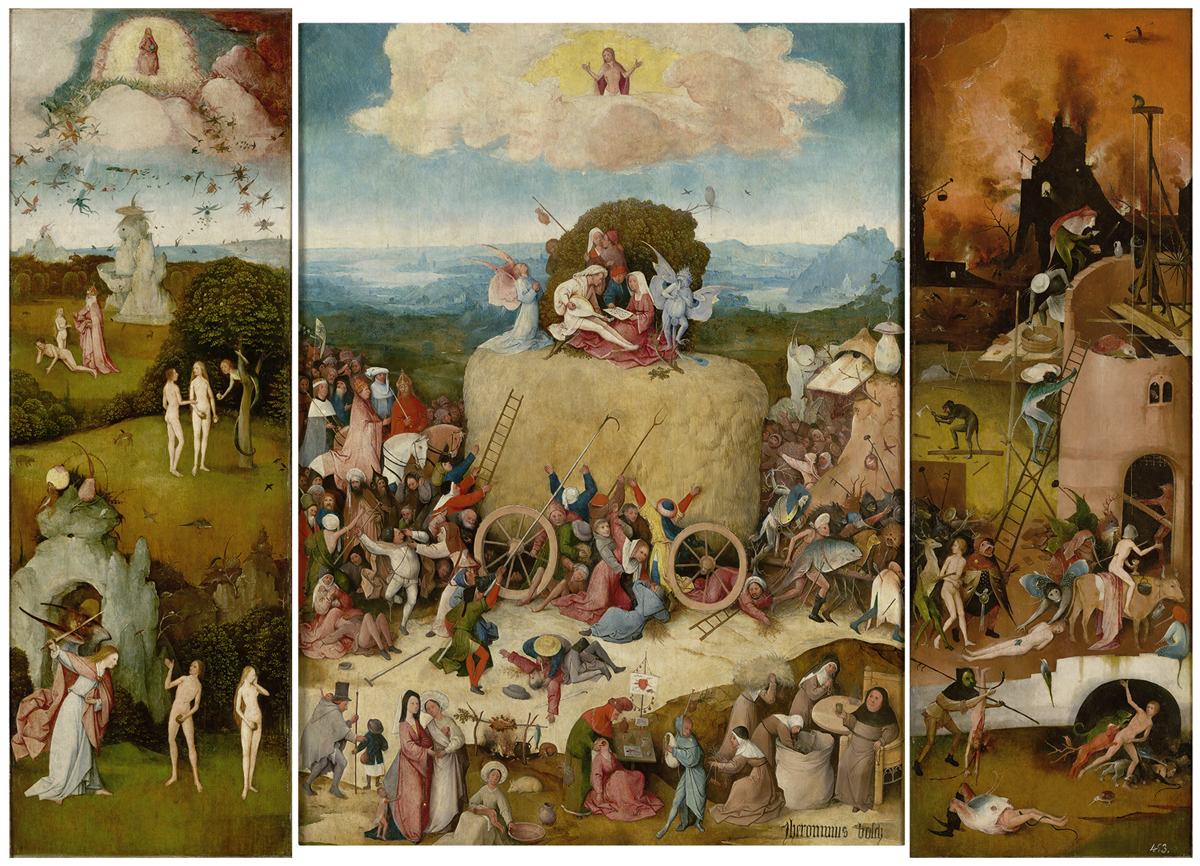

The Haywain Triptych

A cart piled high with hay is pulled by a group of strange beings. They are on their way to hell. Behind the cart there’s a procession of figures from all walks of life, from the emperor and pope to simple peasants. Christ looks down from a cloud over the people of earth. He is small, his presence is discreet. He raises his arms, shows his bleeding wounds. An angel prays, imploring intervention. A blue devil plays his flute-shaped nose. Everyone wants to take some hay, as though it were gold, a man in a hat, his face hidden from us, is driven to murder just for a handful of hay. The ecclesiastics, in the bottom right (above the signature), with a fat monk drinking at a table, attempt to fill their sacks. Zakken-vuller, is the Dutch term (untranslatable) that defines the person filling the sack, but is still reminiscent today of those who want to fill their coffers, in short, an opportunist.

Jheronimus Bosch, The Hay Wain (central panel 133 x100 cm), 1510-16, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. With the special collaboration of The Museo Nacional del Prado. Photo Rik Klein Gotink /Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

In the XV and XVI centuries, the motif of hay was very common in Dutch folklore and had several meanings. In popular literature, and under the influence of religious tradition, its basic meaning was that of ‘futility and transience’, a symbol of terrestrial goods, the grass dries up and withers to nothing; but it also had connotations of avidity, greed, luxury and deceit. A cart of hay often passed through town festivals, as we see in some engravings from 1550-60, and the motif is also present in the songs of the XV century, or in popular sayings: “the world is a hay cart, everyone will grab what they can”.

But Bosch is the first artist to push himself with great audacity on this theme, with a large panel on the truth of life, the pictorial centre of which is a simple shepherd’s staff. The cart dominates and is still heaped high, all around is delirious chaos, life on stage, portrayed with great realism. Episodes of daily life are all around, no one seems to notice the band of demonic and slimy beings leading the procession. An owl observes. The message is clear: those who crave vanity and terrestrial goods will fall into avarice and brutality and will go straight to hell.

Jheronimus Bosch, The Hay Wain, 1510-16, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. Photo Rik Klein Gotink/Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

The hell that awaits us is an incandescent place where devils work on a giant tower. Infernal architecture stretches away in the depth of the painting, in the silhouette of the last tower, the sky is in flames. There are punishments for everyone, in the bottom right a fish monster with human legs devours one of the damned, who seems to struggle in front of us, the souls are marched across a bridge by devils.

From the pink-hued sky of the left panel, the rebel angels rain down from the clouds, they have become toads and flying insects. Their flight appears uncontrollable; they could fly out of the painting at any moment. Below is the Garden of Eden, the narrative zigzags down the image, through the creation of man and woman, original sin, then the banishment from earthly paradise. The figure of Eve, slim and composed (in the bottom right), is in the style of Flemish tradition and is reminiscent of Hans Memling (Eve c. 1485), but it is the smallness of man and women in relation to the Creation that seems to interest Bosch here.

The horizon line is maintained with precision in this work: the landscapes in the background, veiled and transparent like a fresco, take the colour of the sky. At the centre we see a boundless Dutch landscape that mutates into smoke and flames on the right, between the towers and figures at work. A skeletal tree suffocates between the dark constructions and illustrates the heat of hell. With the backgrounds too, Bosch is a great master, a few brush strokes or minute figures, merely hinted at, animate the piece.

Thanks to recent dendrochronological research, the triptych can be dated to after 1510-1512, thus Bosch painted this work when he was already established, in the style of his full maturity. Infrared examination reveals that the underlying preparatory sketches show several stages with different materials, probably made by different hands, that is Bosch and his assistants.

With the triptych open at the exhibition, of course the scene on the front of the shutters can’t be seen as a whole, although the two wings can be admired separately through the glass on the other side of the display. It represents a wayfarer.

Jheronimus Bosch, The Hay Wain (closed triptych, and detail), 1510-16, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

He is a man with a white beard and hair, sticking out of his hood. He looks behind him with melancholy eyes before crossing the bridge. He has a typical staff, but held in a way that is unique compared to the rest of the iconography, his aid against the threatening dog. There is an important change in the painting compared to the underdrawing: behind the bridge was a large crucifix, which he left out during the painting stage. The wayfarer is alone with his decisions.

What is most interesting about it is that this character was painted by Bosch ten-fifteen years earlier. The man is the same, younger, the scene is similar, his size reduced. But that first wayfarer, the tondo preserved at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam (divided in two parts and thus part of a triptych) had a strange destiny in store, starting with its name. There have been various interpretations of the work that over time have spawned different titles: The Prodigal Son, The Pedlar.

Today, however, we know with certainty that we are looking at the Wayfarer Triptych, (De landloper, in Dutch), dismantled over the centuries and ending up in four different museums. The central panel has been lost.

The Wayfarer Triptych, temporarily “reunited”

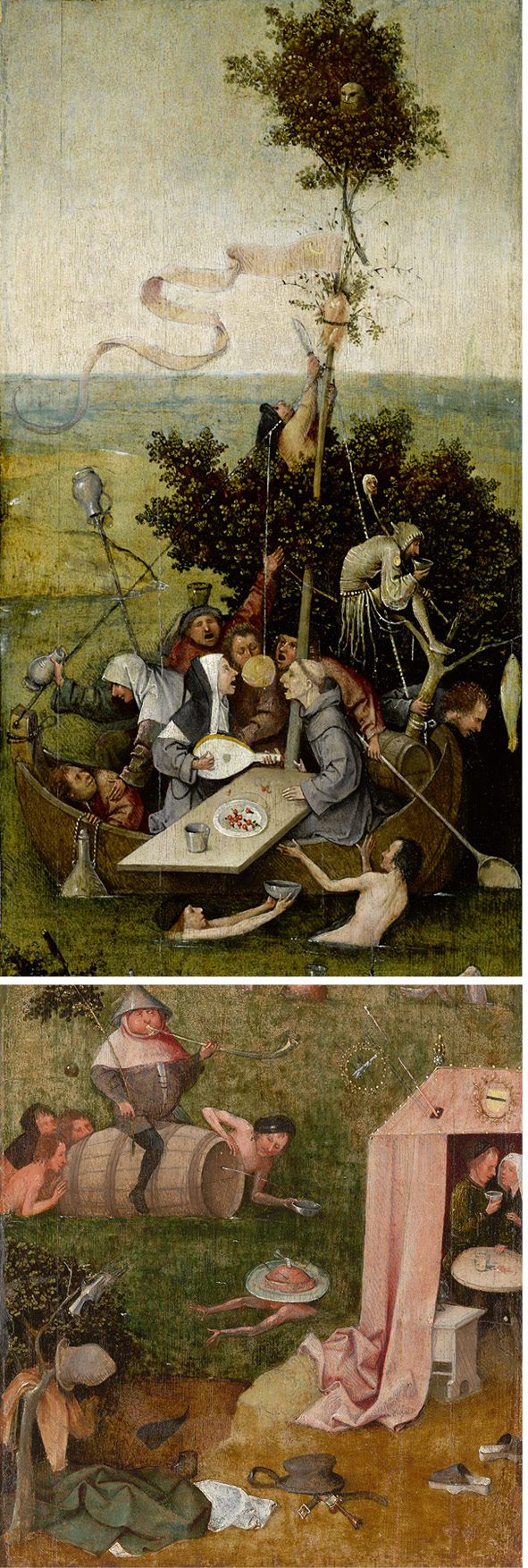

The Wayfarer (Rotterdam) was the scene featured on the exterior of the closed triptych. It was a central tondo originally painted on two wood panels, which formed two shutters. Inside, the left shutter was painted with the Ship of Fools, above (Musée du Louvre) and Allegory of Gluttony and Lust below (Yale University Art Gallery); on the inside of the shutter on the right was Death and the Miser (National Gallery of Art, Washington). Centuries ago, the two shutters were sawn apart, separating front from back. The left inside panel was then cut in two, following the composition; the main part was the ship of fools.

The Wayfarer, at some later date, was joined and cut down to an octagonal shape, eliminating the unpainted parts at the top and bottom of the two original panels. A question remains over the lost central panel.

Jheronimus Bosch, reconstruction of The Wayfarer Triptych, ca. 1500-10

Jheronimus Bosch, The Wayfarer, ca. 1500, 71 x 70.6 cm, Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

The Wayfarer, one of Bosch’s most studied and written about figures, is to be looked at again: it isn’t an autonomous painting, but it is part of a story. He is not a pedlar, there’s nothing to tell us what’s in his pack. He is not the prodigal son, as the pigs’ trough has led some authors to believe. It is everyone’s story, he is ‘Everyman’, the story of man’s march towards a future he does not know. Bosch represents the figure with exceptional realism. The tondo is like a mirror, even in the pictorial treatment around the edge, and this is important to the intentions of its creator. Everyone can see themselves in it: life is a road that presents us with the choice between good and evil every day: Bosch’s favourite theme. This work gives the name to the triptych reconstructed in the exhibition (and in the Catalogue Raisonné, which presents it as a single entry), and thus redefines its meaning.

The narrative proceeds.

From the top: Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools, ca. 1500-10, Paris, Musée du Louvre © RMN-Grand Palais/ Adrien Didierjean. Glutony and Lust, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery. Photo Gotink/Erdmann for the BRCP

The Ship of Fools, the scene on the inside left panel, is a boat crammed with revellers and drunks manoeuvred by a character with a giant spoon. There’s a notable stock of alcoholic beverages, we see a bottle dangling in the water where it’s chilled. The people on board eat and drink until they can no more, a nun and a friar try to bite a cake hanging from a thread, another vomits on the right. The jester turns his back on them and eats alone. At the top of the rocking tree some branches are tied, an owl looks on. The boat looks like it is without government and without purpose.

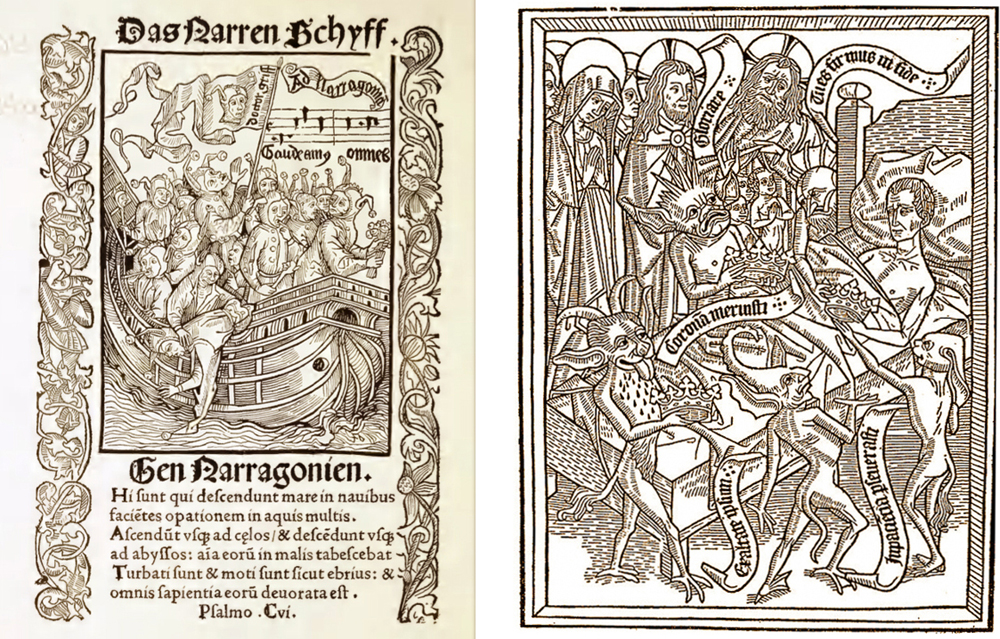

The final destination of this company is also described in the satirical poem by Sebastian Brant The Ship of Fools (Das Narrenschiff, 1494). The Dutch version of the poem, a source of inspiration for Bosch, was published in 1497. “Who takes his place on the ship of fools” writes Brant “sails laughing and singing to hell”.

The lower fragment, the Allegory of Gluttony and Lust, has now been reunited after almost a century of varying hypotheses, due to the fact that in the last two hundred years, the two parts have undergone different treatments, which have altered the colours in drastically different ways. However, scientific analysis has established that they did in fact come from the same panel, and as is clear to see now for the first time, after restoration, the image matches perfectly on the line of the cut.

Hieronymus Bosch, Death and the Miser, ca.1500-10, Washington, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection. Photo Rik Klein Gotink/Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

But the last word of the Wayfarer Triptych is in the right panel, Death and the Miser. The depth of the scene as a whole is instantly striking. The three black areas, the vault in the background, the dark behind the door and the bored devil in the foreground play with the observer, bouncing the gaze around in a triangle. Death makes its entrance on the left, ready to strike with a lance. The avaricious man in the supreme moment must choose between the crucifix and forgiveness, indicated by the angel, and the purse of coins, offered to him by the devil. It is a devil that seems discreet here, but when you’re there in front of the painting it is extraordinarily powerful, creeping in from behind the curtain, it seems to move in the painting. What will the dying man choose? Bosch leaves the scene open and suspended before our eyes, the responsibility of the decision lies with the man alone. But there is more.

The artist altered this delicate moment during the painting phase. In the preparatory drawing the scene has an outcome and a completely different meaning. Under infrared inspection, the drawing revealed is as such: the man clutches a precious goblet in the left hand and with the right has already grabbed the purse offered to him by the demon.

There are no existing documents or sources to go on for a hypothesis about the lost central panel. Observing what has been reconstructed we can at least say that the optical centre of the two side panels is symmetrical: on one side there is the cake suspended in the boat, on the other side the devil with his purse.

As for the ship of fools, we also have a literary reference for this piece: it is the Ars Moriendi, The art of Dying, very popular in the XV century. Putting it very briefly, the message is that the pious will have an easy death. There were many illustrated editions, with the dying man in his bed and the tempting devil, which would surely have inspired Bosch for this work. It is also worth saying that in the age in which Bosch worked, there was especially in the Low Countries a great blossoming of the Modern Devotion, a religious movement that sought to unite the content of Christian faith with individual interiority (in which we can recognise some elements that preceded the Protestant reform). The Bible was translated into Dutch, as we can see in a rare edition on display from 1477, coming from the Crutched Friars convent. The believers could pray in their own language and thus engage with the content of the prayer.

From the left: Sebastian Brant, Das Narrenschiff, 1494; Ars Moriendi, table 7 of 11, Low Countries, ca. 1460

In the triptychs of the hay cart and the wayfarer, Bosh depicts a theme that recurs in his work: the different paths that people take and the moral choices they are forced to make. Man is responsible for what is good and bad in his life. There is no moralism in his message, the scene remains open, even though, like in all Bosch’s work, the seduction of evil is strong.

It is difficult to imagine today, but nobody before him had produced a triptych depicting a wayfarer with his socks torn, one shoe and one slipper. The Flemish paintings of the time mostly represented religious scenes, and non-religious triptychs were a rarity. Bosch creates a new and timeless character, which he reproduces in the two triptychs, ten years apart. Even today’s observer, five hundred years later, is confronted with the central theme of life. From this perspective, Bosch is considered the progenitor of the representation of everyday reality.

A recent exhibition at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam «From Bosch to Bruegel. Uncovering Everyday Life» (which ended last January), revolved around the very fact that Bosch was a pioneer of Dutch genre painting, alongside artists such as Lucas van Leyden, Quinten Massys, and many more anonymous artists who depicted satirical and comical scenes of extraordinary quality.

It is surprising how, when closed, these two triptychs do not present details that are unrealistic as they do when open. Just a stone’s throw from the Noordbrabants Museum, you can experience the “opening-closing” of the triptychs of Bosch’s times at the Jheronimus Bosch Art Centre, a deconsecrated church in which full size faithful reproductions of all the master’s works are on display and can be handled by the visitors. A fascinating experience for cases like the Wayfarer Triptych.

Karel Van Mander, in his Book of Painting (Het Schilder-Boeck, 1604), in a passage dedicated to the life of Hieronymus Bosch, writes: “it would be arduous to describe the surprising, strange fantastic images […] conceived with the mind and expressed with the brush”. Like other masters “he had the habit of sketching and drawing on a white base, proceeding with transparent layers and allowing what was beneath to contribute to the end result”. Van Mander didn’t have a microscope or pigment samples, but he had noticed the “very able and steady” hand; his observations are important because they tell us that the transparency that we see today was also visible back then. Scientific studies have highlighted that often Bosch created the painting as he went along – altering the meaning as we have seen –, and one of the most surprising aspects for the time is that he often proceeded with great skill painting ‘wet-in-wet’, achieving a highly realistic effect with confident and quick brush strokes, which set him apart from his contemporaries. This did not escape the attention of Gillo Dorfles who, in his monograph (Bosch, Mondadori, 1953) noted that “the surfaces look like a photographic plate that has been impressed by the luminescent branches of seaweed”. We therefore have a painter who has not only developed his own visual language, but also adopted very unusual techniques for the time. The liberties he conceded himself were certainly not typical of a late-medieval artist. A unique creative mind then, open to experimentation.

Bosch and his drawings

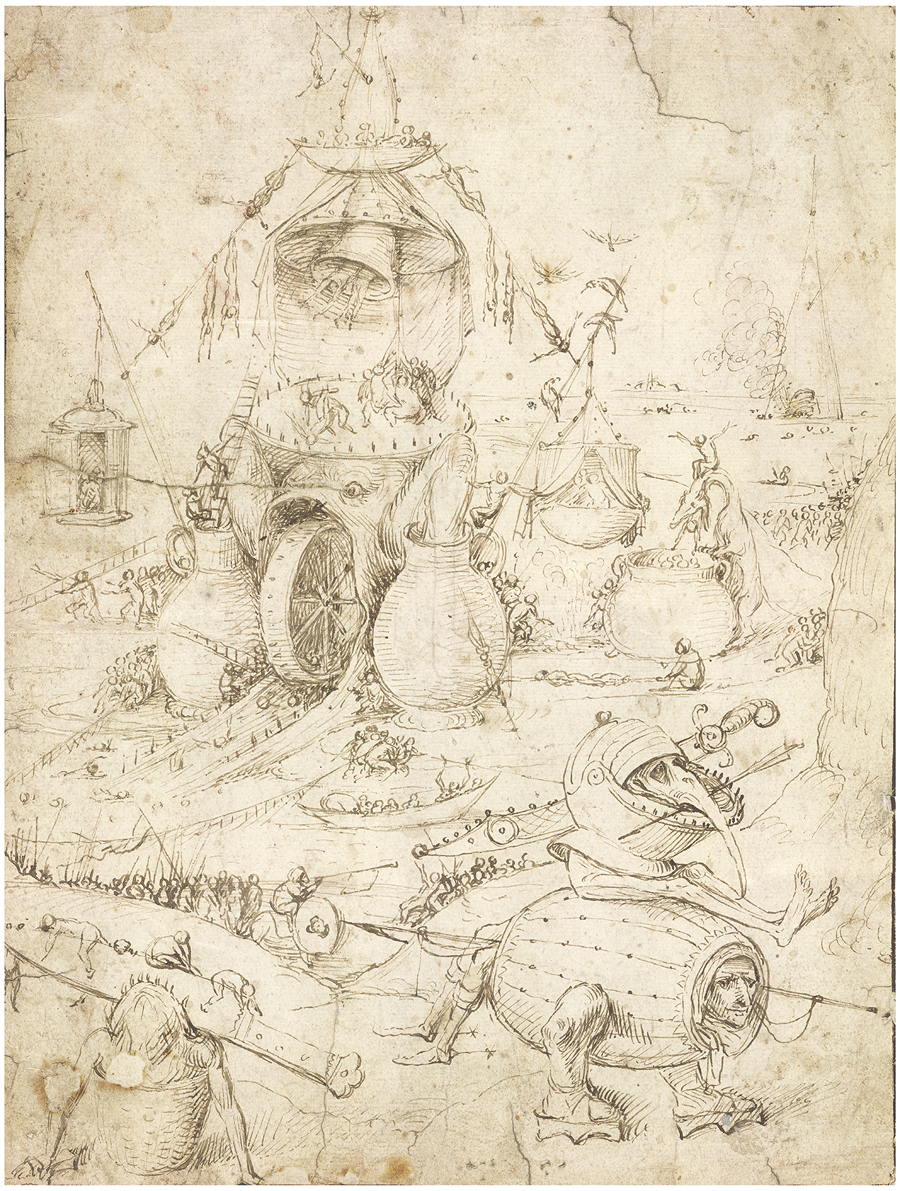

They are delicate sheets, reunited for the first time to form a single corpus that brings us closer to the artist and his inventions, around twenty, today attributed to Bosch. They are at the beginning of a tradition in which paper was used as a support for drawings or sketches and, for the Low Countries, are a real rarity, given that very few sheets of drawings have survived from Bosch’s contemporaries. They are spontaneous sketches, which convey the desire to let his imagination run free and put ideas on paper. Drawing, for the first time analysed as such and not just in relation to the paintings, was a means of inventing or creating new forms for Bosch.

This is well illustrated by a drawing that has recently been attributed to him. It is an Infernal Landscape full of impossible creatures, which comes from a private collection and is now on public display for the first time. The scene is chaotic and frenetic. At the centre is a net for the lost souls, fed to a demonic monster by a giant wheel. Above we see human beings that hang like the clappers of a bell, on the right a dragon vomits souls into a cauldron, below there are people slumped on a knife edge. At the bottom, a barrel containing a face we are familiar with, beastly feet, human legs.

Jheronimus Bosch, Infernal Landscape, private collection. Photo Rik Klein Gotink/Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

In the past it was considered a workshop piece, but the minute details it contains offer a unique example of how Bosch worked on different levels to create his infernal landscapes. A great inventor of disturbed characters, monstrous animals, worker demons. Little elements of great intrigue, just sketched, sometimes minute but effective outlines, have been compared with others of bigger dimensions (also painted in The Garden of Earthly Delights), and documented in the exhibition with clarity.

Among his other extraordinary studies, we can admire Gathering of Birds (Berlin, Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin), in which Bosch shows that he is a keen observer of nature and its behaviour and surprises us with a battlefield populated by multitudes of birds and other animals. Then there’s a sheet of eight little ‘witches’, apparently figures from everyday life but that present strange behaviour: one travels on a peel, with an owl perched behind her; another rides a cartwheel; a third is holding enormous pincers, and so on.

Jheronimus Bosch, Model sheet with ‘witches’, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques

A series of ‘models’, they are not figures that interact with each other. What is unique about this page is that is contains a signature at the bottom, Bruegel manu propria. It is thought that an owner of this drawing, most likely in the XVI century, believed the work to be by Bruegel and added the inscription. Bosch’s work was such a source of inspiration for so many painters that followed him (Bruegel included) that it even created confusion of this kind over the years.

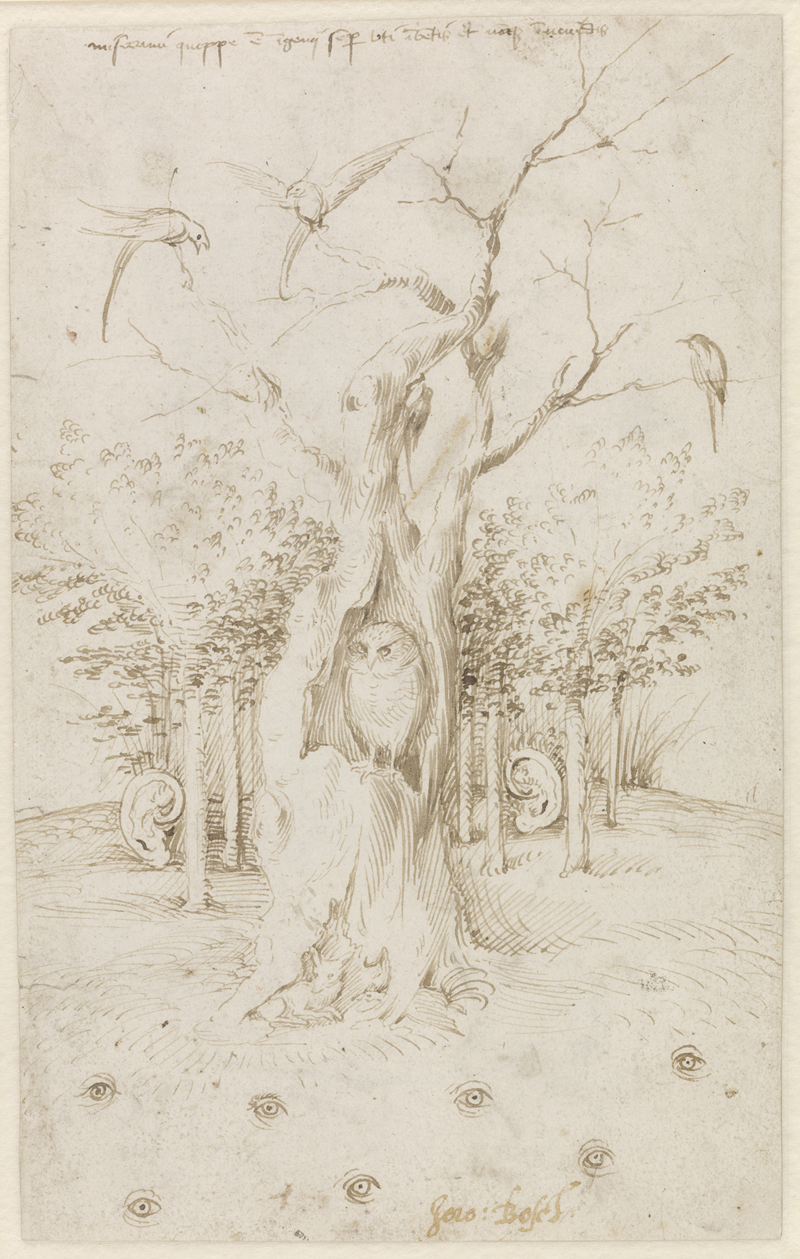

But perhaps Bosch’s most particular and best-known drawing is a real jewel, and carries a motto (written in Latin) at the top, the only inscription on paper considered to be autograph: poor is the mind that always uses the inventions of others and invents nothing itself. It is a small page with a hollow, leafless tree at the centre. Inside it, a disproportioned owl, perhaps this time a symbol of wisdom, watches us. Other birds unaware of its presence perch on the higher branches. A fox is on the ground. Two giant ears stand at either side of the woods, seven eyes are scattered across the clearing in the foreground.

Jheronimus Bosch, The Wood Has Ears, The Field Has Eyes (recto) Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstich-kabinett. Foto Rik Klein Gotink/Robert G. Erdmann for the BRCP

The Wood Has Ears, The Field Has Eyes, an ancient proverb, in Dutch too (campus have oculos, silva aures). A German dictionary from 1500 dedicated to idioms explains it as such: we are always being watched and we should not indulge in behaviour that we would want to remain private. An invitation for discretion? Not only that. Bosch’s implication is more subtle and involves the individual, the artist with his credo annotated at the top of the page; it hints at the name of the city, which means woods (and the municipal seal has an emblem of a tree); it points to the surname chosen by the artist, Bosch (‘wood’) and to the title given to the work, in the inscription at the bottom, Jero:bosch. He plays on the concepts, a magnificent self-portrait.

Bosch, workshop or follower?

For more than a century, historians have been trying to give some order to Bosch’s work, and up until sixty years ago almost forty paintings and just a few drawings were attributed to him. The problem is complex: no painting is dated; Jheronimus came from a family of painters who worked in a workshop; in the XVI century his works were so popular that they were often copied, imitated or forged. There are many forgeries and imitations that bare the painter’s signature in gothic handwriting. As early as 1560, Felipe de Guevara raised the issue in Comentarios de la pintura (1560) “there are many paintings in this style that are falsely inscribed with the name Jheronimus Bosch”. This fact, which goes to show how innovative and revered his work was, has nevertheless been the cause of much confusion over the centuries, including with regards to his historic image.

The objective of the researchers of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project was first and foremost to collaborate with all the museums, study the work systematically, and provide answers that, by discarding all that has been attributed to him mistakenly, help to reconstruct and better understand the work of the artist in its complexity, beyond the dense jungle of interpretation. The results of the scientific research have come together in an impressive monograph in two volumes, the first Catalogue raisonné, which marks an end point and starting point in Bosch studies: Hieronymus Bosch. Painter and Draughtsman, and Hieronymus Bosch. Technical Studies (edited by the BRCP, Mercatorfonds, 2016).

All 25 paintings and the 20 drawings currently attributed to Bosch are analysed. We then have the analysis of nine paintings that the researchers believe to be by ‘followers’, among which is the iconic work (often illustrated in art history manuals), Christ Carrying the Cross (Gand, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, ca. 1530-40); also The Conjurer (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée municipal, ca. 1525) and the fragment of the Last Judgement (Munich, Alte Pinakothek, ca. 1530-40) are included in the same group. The Cure of Folly (Madrid, Museo del Prado ca. 1500-20) and The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (Madrid, Museo del Prado, ca. 1510-20) are indicated as ‘workshop or follower’. A real revolution, given that some of these were previously believed to be his ‘early’ work. The 20 known drawings for the first time constitute an important corpus of the work and are discussed separately, yet also in the pictorial context.

Compare hands according to the Morelli / Erdmann method

Today, there are numerous advanced techniques used to analyse the works, such as infrared reflectography that helps us see the underlying drawings, the study of which, in Bosch’s case, has been fundamental, as the master often created the final composition during the painting phase, deviating from the drawing. In addition, there is the analysis of the pigments, materials and dendrochronology, which allows us to date the wood and the artefacts.

Another outstanding starting point was that of the comparison of the smaller details, inspired by the “Morelli method”. In the late XIX century, the Italian academic Giovanni Morelli (1816-1898, he signed Ivan Lermolieff), defined a new method of attributing historic works based on the analysis of the details that are most easy to overlook, such as the ears, fingers, nails, in short those telling signs that an artist produces almost unconsciously (his theories even attracted the attention of Freud). The researchers picked up and developed this idea using macrophotography; the results are surprising.

Many questions yet remain, but the important thing is that with each generation, a new Bosch is discovered. In seeing the real heart of the work, weeded out in this way, one has the impression of dealing with a melancholy artist, a wayfarer who, with a few possessions in his pack, knows how to observe man and the whole of humanity, nature, things. His paintings contain a refined elegance, courageous finesse; there is no horror in his infernal creatures, in his countless inventions of hybrid creatures, with their disconcerting mutual proportions. He imagined the heat of hell but painted skies that were too true between the flames and smoke to be imagined skies, perhaps he had experienced that hell as a child, or a young man, when half of ’s-Hertogenbosch was devastated by a great fire. It was June 1463. How old he was we do not know.

Jheronimus Bosch. Visions of Genius

Noordbrabants Museum

’s-Hertoghenbosch (Netherlands), 13 February - 8 May 2016

Some of the results of the research can be found on the website of the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, which also documents the work done on the polyptychs preserved in Venice, Bosch in Venice.

The program contains many cultural events: Jheronimus Bosch 500 (www.bosch500.nl)

Since 2011

Since 2011