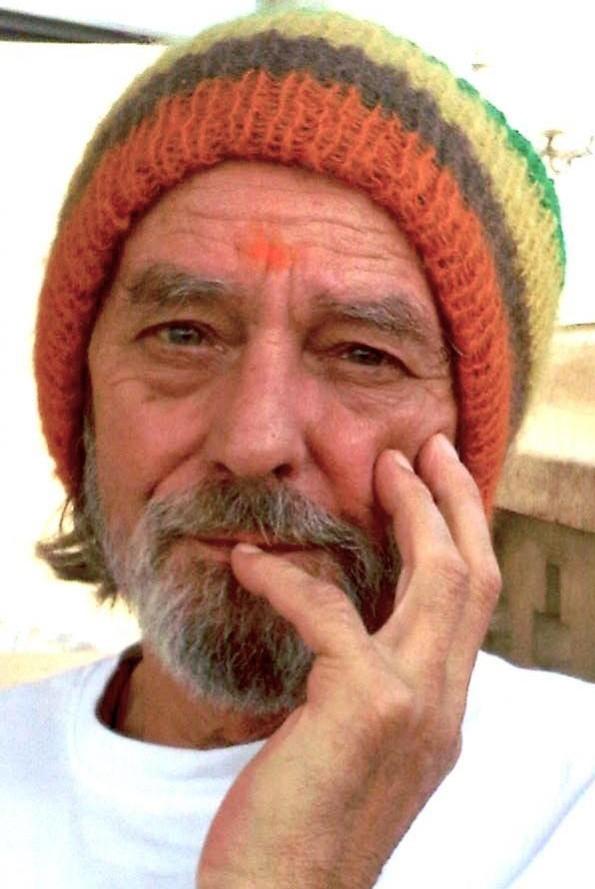

Frank Uwe Laysiepen, the German artist known as Ulay, died on March 2, just a few months before a major retrospective of his work, scheduled for November 2020, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. He was born in 1943, in Sollingen, Germany, during World War II, but his personal and artistic journey really began in 1969, in Amsterdam (his adopted city) to which he was drawn by the constructive anarchist Provost movement. From Amsterdam, Ulay’s journey took him to Paris, Rome, Berlin, London, and then widened to include New York, Morocco, India, Nepal, the Middle East, China, Australia, and Patagonia. It ended in Ljubljana, Slovenia, where he married Lena Pislak and resided in the years before his death.

It is now up to us to rediscover his work: polyhedral, beyond category, non-commercial and uncompromisingly radical. Ulay was a pioneer of Polaroid photography and of performative photography, a prominent figure among European Performance Art and Body Art of the 70s, and an early advocate for ecological militancy through art. His work challenged at their root all concepts of stable identity —national, sexual, political. Yet, even among "insiders", he is known almost exclusively as the companion in art and life of Marina Abramović, with whom he collaborated for fourteen years, from 1976-1988; years which would prove to be the the apex of both of their careers.

I met Ulay for the first time in Amsterdam on a rainy autumn afternoon, in 2010. We took a walk through a Turkish neighborhood, followed by an hours-long freewheeling conversation around his worktable. Ulay was tall and very thin. I was struck by his large hands with which he seemed to sculpt the air as he spoke, and by his intense, whimsical gaze; by his eyes that that changed from steel-gray to light blue. I was taken by his seductive voice—the voice of a great raconteur—and his frankness, and his sense of humor. He was self-assured, without a trace of arrogance. We connected instantly.

We met again a few months later, in New York. He went straight to the point: he wants to write an autobiography in the form of interviews-- he is searching for an accomplice and thinks I may be the right person. We make a weekly appointment via Skype, but it did not work as we both needed real contact. Thanks to the curator Maria Rus Bojan, who had introduced us and believed in the project, we decided to meet at regular intervals, in person. From 2010 to 2013 we set interview times: we got together every few months, for a week-long tour de force of six-hours-a-day of interviews. We met in Amsterdam, Lake Orta, Ljubljana, and New York. I set myself the goal of exploring the connective tissue between his life, his work and his anarchist weltanschauung. We proceeded by themes, places, and ideas, without worrying about chronology. The hours and hours of recording became, Whispers Ulay On Ulay (536 pages, Valiz, Amsterdam, 2014). The interviews were accompanied by an essay by Rus Bojan.

In the last year of preparation of the book, Ulay was diagnosed with stage-four mantle cell lymphoma. He underwent repeated cycles of chemotherapy and hospitalizations, facing the disease with exceptional serenity and courage. He never wanted to stop work, so we continued the interviews before and after each hospital stay. I was in awe of his physical and psychological fortitude.

Ulay claimed that his "place in the world" - the platform from which he operated - had little to do with the world of contemporary art. He has never had a studio nor assistants; he hated the idea of a “ signature style.” which is so convenient for audiences and critics. For most of his career, he was not represented by a gallery, nor did he benefit from government or institutional support. He produced aphorisms and poems, photographs, collages, performances, body art, sculptural objects and installations, videos, drawings, but never a painting. He rarely sold his work. He enjoyed the support and friendship of other artists, whom he saw as travel companions. The idea that there was something called “the art market” he dismissed as laughable nonsense. Laughter was his first defense against anything he opposed.

Ulay’s moments of contact with the public were always attempts to open a dialogue, to build an ideal community, or, sometimes, occasions for violent confrontations that gave rise to mutual misunderstandings. He was always guided by an irrepressible curiosity, a strong moral compass, and the need for freedom in his life and work.

To evoke the man and the artist, I am choosing four emblematic moments/works.

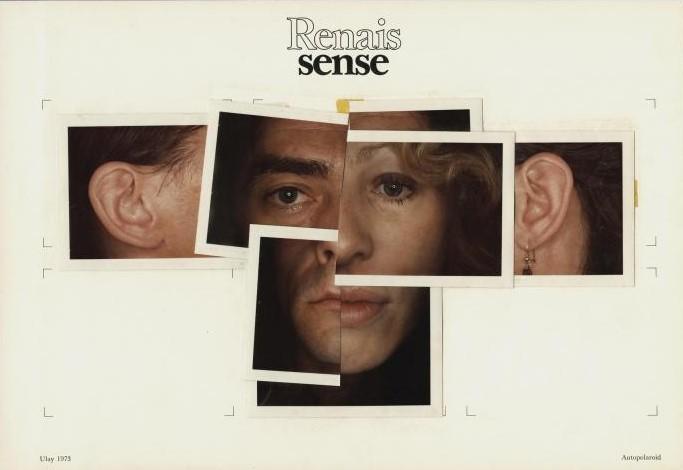

Ulay, Renais Sense, 1973

Ulay - The builder of temporary identities.

After leaving the art academy without completing his degree, in 1969, Ulay took his car, two books, a typewriter, and a Polaroid camera and left Germany and drove to Amsterdam. He left behind a commercial photo lab, a wife and a three-year-old son. He wanted to "de-Germanize" and build a new identity. It turned out to be a definite split. He told me, “I left Germany because of a deeply felt conflict I felt. I disagreed with what was going on socially, politically and economically in Germany at the time. I needed to un-learn to be German in order to discover myself.” In Amsterdam, where hippies and the Provos anarchists were experimenting new social codes, he found the antidote to the "cocktail of material interests and industrial power that dominated in Germany."

As soon as he arrived, he renamed himself. By synthesizing his name (Uwe) and last name (Laysiepen), he simply becomes Ulay. (Years later, when he discovered that ulay in Hebrew means “maybe,” he was amused by the coincidence) In Amsterdam, he began a process of searching for a temporary identity through un-learning, giving up. The first Polaroid series, self-portraits, and collages, in which he often portrays himself as half man and half woman, are an attempt to answer questions that he will continue to ask himself all his life: who am I ? Who can I be? Who do I want to become?

Changing his name ( which he has done at several junctures in his career) always signaled, the beginning of a new artistic phase. Forty years later, when environmental emergencies become a primary concern in his work, he focused on access to drinking water in various parts of the world. "Recently, I decided that whenever I meet someone, I will introduce myself as ‘Water’. Think of it: our brains are 90% water, and our body about 68%. Not Waterman, but simply Water: it makes people curious. They say: ‘pardon?’ and I say again, ‘Water’. This immediately starts the type of conversation I want to instigate."

Ulay, Berlin action, 1976

Ulay — The provocateur

Berlin Action- There is a Criminal Touch to Art. In 1976, Ulay met Marina Abramović: love at first sight soon turns into a symbiotic union. They decide to go at it together and collaborate, but before starting, they decide that they should each complete a solo work. In December, Marina was invited to Berlin for a series of performances, entitled Freeing the Body. Ulay went along to photograph her. Once there, he conceived his own “action.” The idea occurred to him while visiting the Neue Nationalgallerie where he came across Carl Spitzweg’s famous painting, Der arme poet (The poor poet). Spitzweg, Hitler’s favorite painter, was a romantic figurative artist from the Biedermeier era. In German secondary schools, Der arme poet, was presented as "the German painting of the 19th century.” The historical and symbolic weight of the painting immediately appealed to Ulay, who decided to use the painting as a catalyst for a political/artistic action.

In those years, in Berlin, there was a semi-illegal neighborhood called Kreuzberg, which was filling up with newly arrived Turkish immigrants, who were often subject to discrimination and violence. In the previous day before his encounter with the painting, Ulay had spent hours studying and photographing the neighborhood. After seeing the Spitzweg in the museum he returned to Kreuzberg and made friends with a Turkish family. He explained that he was a contemporary artist who wanted to bring the issue of Turkish immigration to national attention. He asked to visit their home. In the living room-kitchen, he notices a painting on one wall. He asks for permission to return a few days later to replace it with another painting and to photograph it with the family gathered around. He promised that it would take half an hour at most. The family agreed. That afternoon, he returned to the Neue Nationalgallerie to focus on his plan, like a robber visiting a bank before a heist. The Spitzweg painting is located one floor below the entrance. The room has two large wooden doors which are always closed, to maintain climate control. From that room, to reach the exit, one must climb a flight of stairs, cross a large entry hall where the ticket booths are located; the revolving doors are located beyond them, at the entrance. Anticipating that the revolving doors would lock in the event of an alarm, Ulay’s attention went to a small side emergency exit. The emergency exit door too, he supposed, was probably connected to the alarm system, yet it had a seal that hopefully would give in if pushed hard. He wrote down the itinerary, and the next day jumped into action.

Ulay and Marina where at that time living in a black Citroen HY van. He parked the van in front of the museum, about thirty meters from the emergency exit, leaving the engine running. Then he entered the museum and reached the painting. Choosing a moment when the guard was occupied, he detached it from the wall by severing the wire support with wire cutters. When the siren sounded and the lights began to flash, he took strode towards the stairs with the picture under his arm. As he had speculated, the revolving doors locked, but he was able to slam open the security door with his shoulder.

Amidst the yells of the guards and the museum crowds, he made it outside, chased by three guards who did not hesitate to shoot at him, aiming for his legs and just missing. In the race, he stumbled on the gravel, which had been made slippery by the snow and fell; got up, ran again, arrived at the van and drove away. (The escape was documented by Jorg Schmidt-Reiwein, a cameraman, who was stationed in another van). Immediately, the police and an anti-terrorism squad begin to chase him – the authorities assumed it was an attack by the Baader-Meinhof gang. In the van, Ulay heard the hum of the helicopters following him from above.

Once in Kreuzberg, he entered the apartment of the Turkish family, replaced the picture on the wall, and took photos of Der arme poet with the smiling Turkish family around it. Then, he went down the street and called the museum from a phone booth. He asked for the director, and said: “My name is Ulay, I’m an artist, I want the director to come and get the picture in Kreuzberg.” He gave the address. Within minutes, the block was surrounded by special forces in riot gear. The incredulous museum director, escorted by policemen, arrived at the home of the Turkish family and inspected the (fortunately unharmed) painting hanging on the wall, while the police arrest Ulay. The next day, Ulay made the front page of the major German newspapers. He was arrested, tried, and sentenced, to 56 days in prison. He jumped bail, and fled to the Netherlands, after which he was not allowed to set foot in Germany for years. What is most striking about There is a Criminal Touch to Art—the title he gave to the action--and which will remain a constant in Ulay’s work, is that he relied exclusively on his own body—agility, speed, firm nerves—to carry it out. The body alone, in its absolute nakedness and vulnerability, become his instrument, his artistic language as well his means of political struggle. "I never thought that we could change the world with art,” he told me, “but art can and should point our attention to uncomfortable issues."

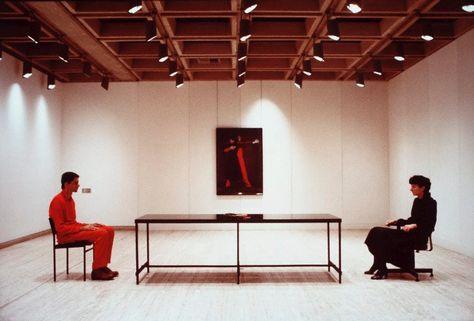

Marina Abramović and Ulay, Nightsea Crossing, 1980

Ulay — Movement becomes immobility

Much has been written about the so-called Relation Work with Marina Abramović. I simply want to recall some aspects of Nightsea Crossing, which is, in my opinion, the high point of their collaboration.

Ulay describes it thus: “A man and a woman, seated on opposite sides of a table, motionless, in silence. That’s all". The performance is the result of a series of trips around the world, new interests, philosophies, and approaches to life. After years of exploring movement, sound, and physical endurance, with Nightsea Crossing, Ulay and Marina were questioning whether their mere physical presence, their "being with the public" was enough. Could one consider it a performance? It was an attempt to reduce everything (their work as performers, but also their life experiences) to the bare minimum. And to compare Western and Eastern notions of time, immobility, and the flow of life.

The starting point was a trip to Australia, in 1980. "We found ourselves alone in the Central Australian Desert with temperatures reaching 48 degrees. At those temperatures, immobility is almost mandatory. Watching a reptile breathing is truly an activity and perhaps the best you can do. In that heat, you can only vegetate, like a plant. Before you move, you ask yourself ten times if it’s worth it. Living in those circumstances made us think in a completely new way about movement, action and I would say life. It forces you to save energy and eliminate anything superfluous. On the other hand, it makes you discover the beauty and mystery of being. What it means to simply be .” For Ulay that trip marked the discovery and a long-lasting fascination with the Central Desert Aboriginal culture,“ I felt deep respect and admiration for the Aborigines, an amazing people who survived so long on barren terrain, in hot temperatures, still maintaining and treasuring a collective memory. Memory about a “dreamtime” that precedes history. Theirs is a culture that does not much value material things. Their civilization evolved in a very different way. The Aborigine’s society is not based on economic value; they have their own values. One of them is memory.”

A work of enormous duration, ambition, and purpose, Nightsea Crossing required 5 years of preparation. “We wanted to put ourselves in the ideal physical, mental and spiritual condition to be able to undertake the new performance, so we went to India. We were vegetarians for five years. It was a way to increase mental clarity in view of the long fasts that Nightsea Crossing would entail." To prepare for immobility, they explored meditation techniques. “We soon understood that meditation would be a necessity, moreover, the lifeblood of the work, so we went to Bodhgaya to study Vipassana. That ancient form of meditation proved essential for us to learn how to manage internal and external sensations during the performance, as well as physical pain and hunger. But the biggest gift I received from meditation was learning not to think, not to hold on to thoughts.”

“Vipassana meditation is a gift and a very useful tool in daily life as well as in the most extreme situations." Many aspects of this performance are based on the Veda tradition. “We were fascinated by numerology in the Veda texts according to which each individual is identified by numerical values. Our numbers were the basis for the duration in hours and days in which we would be sitting in silence with the public." Nightsea Crossing was first performed in Sidney for 7 hours on 16 consecutive days in 1980. During that time, Ulay and Marina observed complete fast ("I ate an almond a day, I love almonds, Ulay recalled) and silence. The performance was repeated on 90 non-consecutive days in museums and galleries on five continents. The simplicity, purity, and rigor of the work fascinated the public, which inevitably (even when it lacked concentration or attempted disruptions) became an essential component of the piece. Much more than a mere extreme test of endurance, Nightsea Crossing, lends itself to a multitude of readings, not least a ruthless criticism of marriage. There is something sadly universal in the image of a man and a woman at a table sitting in silence with nothing more to say to each other. As in a Beckett play, humor and tragedy meet one another.

Ulay – Ontological photography: 1:1 scale.

Ulay had an encyclopedic knowledge of all aspects of analog photography-—optical, chemical, mathematical, industrial. In the early 70s, Edwin Lang, the inventor of Polaroid photography, selected ten artists, including Ulay, to whom he always gave free access to Polaroid cameras and an unlimited amount of film to explore the creative potential of “instant photography.” From then for the rest of his life , Ulay continued his 360 degrees exploration of this invention, which condenses exposure, development, and printing in a single moment. When Ulay spoke of Polaroid, understood both as a camera and a process, it was as if he were talking about a lover who never ceased to amaze him. In his home in Amsterdam, he kept an archive of his Polaroid photographs methodically cataloged and preserved.

He was proud to say that in his entire life, he had not sold more than five of his Polaroid photographs.

Around 1980, Lang built a few studio specimens of the 40X80 model, housed in a wooden structure of about two square meters. These produce high-definition images superior to today’s digital cameras. Lang conceived of the project in order to take the best possible photographs of the frescoed ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. From the start, Ulay sensed that this camera could fulfill his dream: to photograph the human body, on a 1:1 scale. Together with Chuck Close, Lucas Samaras, and Julian Schnabel, Ulay was among the artist who experimented with the Polaroid 40X80 most frequently, sometimes physically entering the camera and manipulating the film with plastic gloves during the instant development.

The results are of great interest, both artistically and conceptually. "The first photos I took with that huge camera were four images, for which I used a scrim diffusing foil, a beautiful material, a bit like fiberglass. I put a spotlight behind the foil, with a yellow filter. So, we had an illuminated yellow background against which we took four photographs of Marina and myself. We wanted to represent the four stages of life, according to Delacroix.” In 1987, Ulay rented the gigantic Polaroid camera and installed it at the Gallerie Clairefontaine in Luxembourg. Then for a few days, he poses, one at a time, a large sample of the Luxembourg population: a child, a nun, a bum, a banker, a housewife, a policeman, etc. In the end, he covered every wall of the gallery with all the portraits, like a human map. "The Luxemburg portraits" was one of the most visited exhibitions that year in Luxembourg, "Art also serves to see/show oneself individually or as a group."

The challenge of creating photographic images that do not make the subject smaller has accompanied Ulay in different moments, with or without the help of the large Polaroid cameras. During his stay among the Pitjantiatjara Aborigines in the desert in southern Australia, Ulay developed what he called “afterimages.” At night, in the soft light of a fire, he built and fixed1.80cm X 70cm wooden frames into the ground, like doors, and covered them with photographic paper. He asked Aboriginal women to dance one at a time in front of these "doors.” During the dance he activated a flash that gave enough light to catch a trace of the dancing body on the photographic paper, then treated with a fixative. The result are phantasmagorical “presences,” or “afterimages.”

Ulay’s work, as a whole, has not yet been the subject of critical analysis, with the exception of essays by Thomas McEvilley and Maria Rus Bojan. I want to conclude with an invitation to rediscover Ulay, starting from his 1:1 scale Polaroids, in which the correspondence between image and subject raises profound and artistic and ontological questions. I can hear him tell me: “Photography, for me retains an alchemical element, something magic. There is no art without magic."

A short bibliography on Ulay

Ulay Life-Sized, curated by Matthias Ulrich, Schirin Kunsthalle, Frankfurt. Spector Books, 2016.

Whispers. Ulay on Ulay. Maria Rus Bojan and Alessandro Cassin. Valiz, Amsterdam 2014

Art, Love, Frienship Marina Abramovic and Ulay Togther & A Part, Thomas McEvilley, Documentext. McPherson and Co, New York, 2010.

Ulay The First Act, Uwe Laysiepen and Thomas McEvilley, Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 1994.

Since 2011

Since 2011