We are in the eye of a perfect storm. The new hotspot of the pandemic is down here in Louisiana, and for weeks the spotlight of America has been focused on us. We are the testing grounds of the disaster that threatens to overtake the entire South.

New Orleans is the epicenter. Here the mortality rate comes close to that of New York City and hospitals are overwhelmed. The contagion started at the Mardi Gras parades that attracted 1.5 million visitors in February. From there, it made its way northbound all the way to Shreveport, the city where I live.

Few people had heard of Shreveport, until it jumped to national headlines as the test case the US was waiting for. Shreveport is neither a touristic destination nor a hidden gem. It had its moment of glory at the end of the 19th century as a port on the Red River and now is the capital of a small rural region.

Its main attractions are the big casinos along the river. People come here for shopping, college classes, and medical appointments. Other than that, it is an anywhere spot in the myriad of small towns and villages that compose the heartland of America.

The failure of the richest country in the world has been written these days in metropolis. In New York, Los Angeles, Seattle. But what happens when the pandemic swallows a medium-sized city in the South, in one of the poorest, youngest populated and least healthy states? At the moment, the feeling is like being on the deck of the Titanic. The water rises, and the orchestra plays.

Tomorrow no one can say it wasn’t coming. We knew about China. We knew about Italy. However, seventy days lapsed from the first epidemic notification in China before Trump would take the situation seriously. And it is all time lost in terms of countermeasures and public opinion. At this point, America is fractured – those who worry and those who shrug. After weeks of hearing from the President and Fox News that the “Chinese virus” is a hoax made up by democratic media, a plot against America, part of the country now believes it.

It is a “partisan gap in perception”, as Ronald Brownstein defines it in The Atlantic. And the polls promptly highlight it. Democrats, concentrated in urban areas, express much more concern about the pandemic, are more prone to change their personal behavior and are more attuned to what happens in the rest of the world.

In rural and Republican-leaning areas, such as Louisiana, diffidence prevails. Here people distrust elites, media, foreigners, and science. They mistrust the central government – anti-government militias are in constant training. It is the rural against the city, the old against the new. In the South, groin of the America Bible Belt where society gravitates around church ministry, there is also a constant struggle of faith against reason. Few believe the virus is a real threat or are open to restricting their range of activities, and considering these premises it is not surprising.

An emblematic figure in this story is Tony Spell, pastor of Life Tabernacle Church, a megachurch in Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s capital. As the pandemic ravages and the governor forbids gatherings of more than ten people, Spell refuses to close down.

Hundreds of faithful, mostly elderly, are shuttled to services by church buses. They pray as they always had, close to each other. The pastor is arrested but then starts right over. "They would rather come to church and worship like free people than live like prisoners in their homes," he said to the reporters. Anyway, he said in the sermon, “there is nothing to fear”. Episodes like this happen all across the South.

In a singular coincidence, the same day Italy is locked down, New Orleans records the first case. A few days later, while the epidemic explodes, Louisiana governor John Bel Edwards (D), closes schools, universities, public activities and implores citizens to practice social distancing – you must keep six feet apart, not shake hands or hug.

A week later comes the stay-at-home order. Non-essential workers must stay at home. Other than that, one is allowed to take a walk, to exercise outdoors, to go to the supermarket and pharmacy, and purchase take-out food. We are “the new Italy”, admonishes the governor and again he invites respect of the rules.

The system adjusts with that American speed that still amazes me. Without a bat of the eye, teaching activity moves online and so do offices, gyms, and retailers. Restaurants accelerate on take out and home deliveries. Unemployment shoots up, and supermarkets hire full speed. In front of the cashiers, clear plexiglas barriers pop up; early shopping hours for those over 60 debut, grocery deliveries multiply.

But many consider it overkill, if not an abuse of power. Streets fill up with biking families, joggers, and groups with dogs. More than a pandemic, it looks like a holiday. Cell-phone data show that average mobility goes down just 25-30 per cent.

It also happens in the rest of the world. Even in the Hapsburg Trieste, after four weeks of isolation people start to feel restless. In the United States, however, another cultural code comes into play, as Ed Jong explains in The Atlantic. “Its individualism, exceptionalism, and tendency to equate doing whatever you want with an act of resistance meant that when it came time to save lives and stay indoors, some people flocked to bars and clubs”. In a time of pandemic, the values dearest to the American spirit are revealed as a double-edged sword. And so are the sociality and hospitality habits that make the South unique.

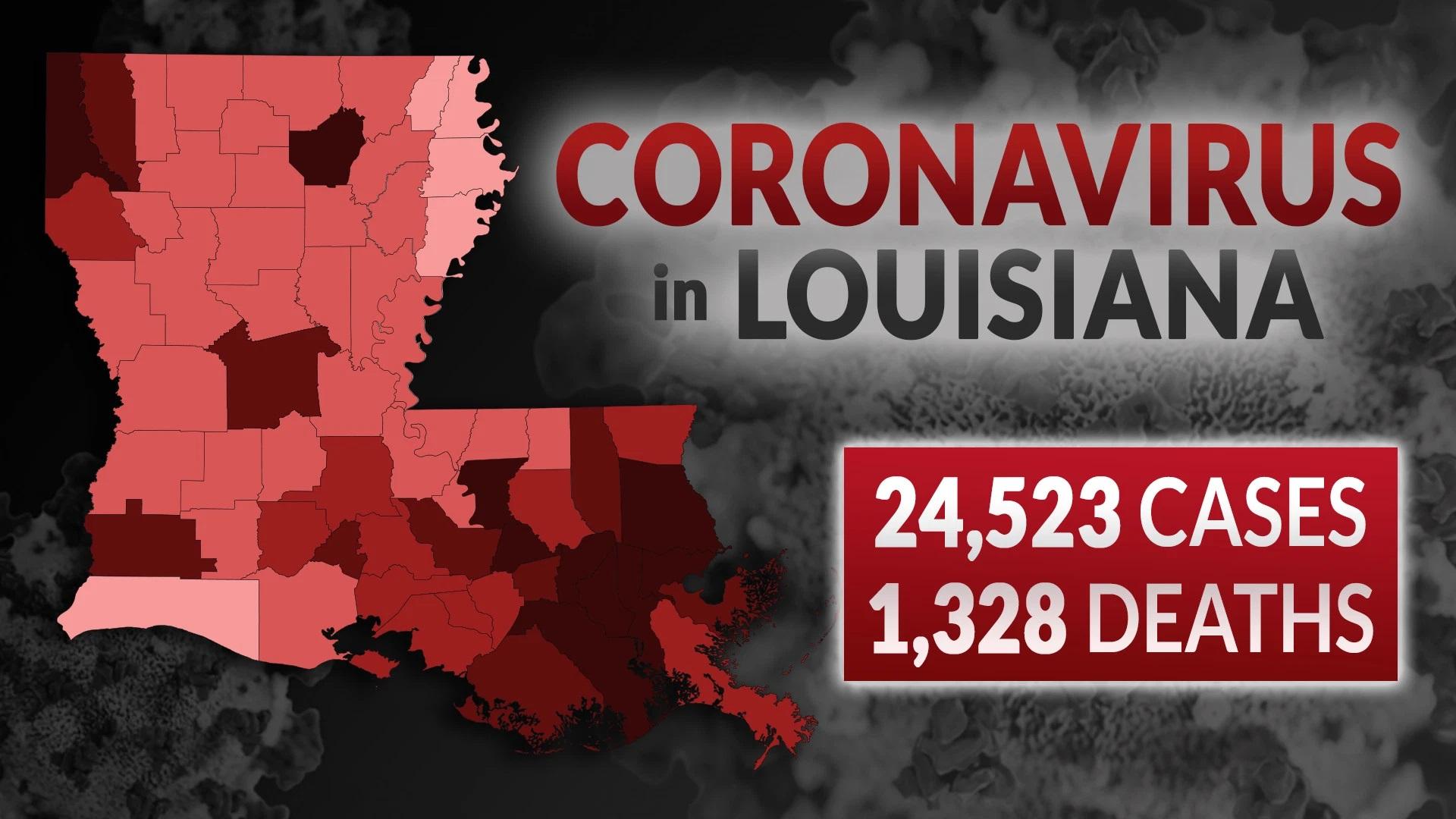

For that too, the contagion advances with impressive rapidity. Louisiana counts less than six million people, more or less the equivalent of the Lazio region. As I write, at the beginning of April, the number of cases passed 16 thousand and deaths are close to 600.

This tragedy turns the statistics upside down. The elderly die. The young die. Women more than men. Above all, die the African Americans that now represent 70 per cent of the virus death toll and only 32 per cent of the population. The epidemic finds a precious ally in the diseases of poverty – diabetes, obesity, hypertension, renal and cardiovascular problems. In New Orleans, hospitals risk not having enough mechanical ventilators before Easter.

The federal government announced it will cover the medical expenses of the uninsured (as 42 percent of African American here are). However, it is easy to picture the multitude of the sick who will not show up at clinics or hospitals. Between minorities and the health system runs a longstanding mistrust. And even among the majority, calling in sick can mean no sick pay or getting fired.

There is nothing new in this story, except the urgency. The pandemic just unveils the face of a society where health is a luxury, being poor is a crime, and differences are abysmal. The virus confirms we are not on the same boat – we have never been. There are those who have a job and those who have lost it. Those who own a home and those who do not. Those who are insured and those for whom getting sick can mean bankruptcy. Those who raid the supermarkets and those who suffer hunger.

In Louisiana, the schools reopened momentarily. Just a couple of hours, on Monday mornings. They distribute meals to the students for the rest of the week: four breakfasts and five lunches. Too many children here, if they don’t eat at school they don’t eat at all. As far as the food banks, for days they have been desperately appealing for donations in the entire state. Supplies are being exhausted and the demand is infinite. The charities struggle to cope with the weight of an emergency of this extent.

Many governors in the South were late or still struggle to put in place mitigation measures. One fear is that the regimen of restrictions will end up killing the patient. Recovering from such an economic breakdown appears like an impossible task, for an area marked by poverty and historic delays. What will be the weight, in terms of health and future perspectives, on future generations?

And we come back here. What happens when the pandemic lands on a medium-sized provincial city? Researchers at Ochsner LSU Health work without rest. Clinical trials, experimental therapies. Will we be able to cope or will we be overwhelmed like New Orleans?

Every day at noon, the infection data are updated on the government website. Tomorrow again, I will copy the numbers on the long list that I compile since the beginning of the pandemic. I will try to make sense of the numbers. Voices, faces, names. And as every day before, I won’t be able to. Then I will close the notebook and I will imagine myself elsewhere. In Trieste, for example. When the storm closes in, you only dream of going home.

Since 2011

Since 2011